Lost Clubs: The Devonshire Club (1874-1976)

Originally a Liberal club, which became a bastion of Tory businessmen

The former clubhouse of the Devonshire Club, pictured last June, after the removal of scaffolding.

Having recently looked at the gambling club of Crockford’s, I thought it only too appropriate to look at a club which followed, occupying for over a century the same building at 50 St. James’s Street: The Devonshire Club.

If the Devonshire Club is remembered at all today, it tends to be as part of the full name of the East India Club (the East India, Devonshire, Sports and Public Schools Club), or as a mysterious-looking boarded-up edifice on St. James’s Street, directly opposite White’s. But it had a fulsome history in its own right, with some entertainingly unexpected twists and turns.

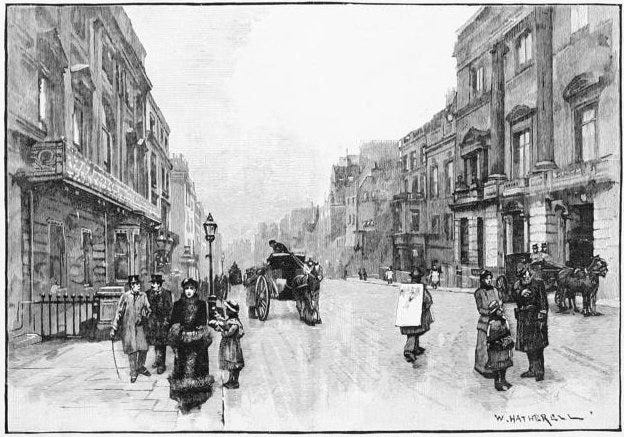

A view down St. James’s Street from the junction with Piccadilly, with White’s on the left, and the Devonshire Club on the right. (Picture credit: William Hatherall, ‘St. James's Street. Showing White's and the Devonshire Clubs’, in Joseph Hatton, Club-Land, London and Provincial (London: J. S. Virtue, 1890), p. 31.)

Origins

The roots of the Devonshire Club go back to 1868. London clubs had flourished in the 1860s, doubling from 30 to 60. Part of this wave was made up of the growing number of “Junior” clubs (like the Junior United Service Club founded in 1827, the Junior Athenaeum and Junior Carlton Club both founded in 1864, and the Junior Naval & Military Club founded in 1870). These were insitutionally independent from their namesakes, and were often larger and offered more sumptuous premises. And against this backdrop, there was talk of setting up a Junior Reform Club.

(There had briefly been a Junior Reform Club in 1866-7, but that was as part of a confidence trick - and is another story, for another Substack post…)

Aside from Peel’s second ministry, the period between the first two Reform Acts (1832-67) had been dominated by the Whigs/Liberals in government. For the Conservatives, this offered the chance for reorganisation, and private members’ clubs were at the heart of these efforts. By the 1860s, the Conservatives had grown to dominate much of political Clubland. Although White’s had ceased to be political by this time (it was more Whiggish in the mid-19th century), conservatitives still had several choices between the Carlton Club (launched in 1832), the Conservative Club (1840), and the Junior Carlton Club (1864). Although the traditional Whig citadel of Brooks’s remained firmly aligned with the Liberals until the 1880s, the Liberals could only point to one post-Reform Act club which had endured: the Reform Club (launched in 1836). Consequently, with the pressure on the Reform Club growing, and the membership still restricted to 1,200 at the time, there was strong lobbying among Liberals for a new, larger club. This was particularly true at a time when the Liberals were on the up, and would go on to win the general election of November-December 1868.

Lowes Cato Dickinson’s life-size portrait of Gladstone’s Cabinet of 1868 (painted 1869-74) was acquired by the Club in 1883 and hung in pride of place until it vacated 50 St.James’s Street. It was purchased by the National Portrait Gallery in 1977, and is now on loan to the Parliamentary Art Collection, hanging in Committee Room 14 of the House of Commons. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Foundation.)

Once the Liberals formed a government, discussions of a new club were placed on the back burner. When Gladstone’s Liberal government was defeated in 1874, the need for a new Liberal Club once again came to the fore: indeed, as I have observed elsewhere, electoral defeats have tended to be much more of a spur than victories, to setting up new political clubs.

The new club was explicitly launched as a Liberal club - from 1874 until 1915, its first rule was:

“The Devonshire Club is a Political Club on a broad basis, in strict connection with and designed to promote the objects of the Liberal Party. Those persons are only eligible for admission who, entertaining Liberal principles, recognise individual freedom of politial opinion, combined with unity in Party action.”

The Managing Committee of the Club held its first meeting on 14th July 1874, christening it the “West End Liberal Club”, or the “Liberal Club” for short.

It was not to use that name for long. Early committee meetings were held in Devonshire House, under the chairmanship of Marquess Hartington MP (later the 8th Duke of Devonshire); and in November it was decided to abandon the “Liberal Club” moniker, and name the Club after the Devonshires. Over the next century, four successive Dukes of Devonshire were to remain involved in the Club’s affairs, each serving as Club President.

The Devonshire Club’s portrait of Liberal Chief Whip William Patrick Adam of Blairadam MP, an early champion of membership amongst Liberals. (Picture credit: Parliamentary Art Collection)

The Liberal Party’s Chief Whip, William Patrick Adam of Blairadam MP, was tasked with seeking out members, signing up at least 300 of them, and taking out advertisements in “345 Liberal newspapers throughout the country.” The founding Managing Committee was heavily party-political: of its 21 members, 14 were Liberal MPs, and 3 were peers.

Although the intention was for the Club to administer a political fund to support Liberal candidates at general elections and by-elections, along the model of the Carlton Club for the Conservatives and the Reform Club for the Liberals, the Corrupt and Illegal Practices Act 1883 stopped the Club from holding and distributing independent funds.

Overall membership was to peak at 1,300 in 1884, had dwindled to 900 a decade later, and reached 1,300 again by the early 1960s, before dropping to 700 by 1975.

Building

The original late-Georgian Crockford’s clubhouse, constructed in 1827 to designs by Benjamin Dean Wayatt and Philip Wyatt, underwent numerous alterations from C. J. Phipps in 1870-5 to suit late-Victorian sensibilities, including the creation of a new facade.

The building had undergone several changes of use since the closure of Crockford’s in 1846, including as the Military, Naval and County Service Club from 1848-51, as well as stints as a hotel, an art gallery, and latterly, an auction house. Phipps’ design alterations were originally with a view to modifying the building into an auction house; but the 1874 bankruptcy of the auction house’s company placed the building on the market, and the Managing Committee of the Devonshire Club took the opportunity to ask Phipps to make further alterations, to convert the building back into a club. Completion of the alterations in 1875 led to a grand opening ceremony on 1st March that year.

The building made extensive use of the original Crockford’s clubhouse, with the original gaming room being repurposed into the main Coffee Room, for dining on the first floor.

The Coffee Room of the Devonshire Club. This painting still hangs in the front lobby of the East India Club today. The tweed-clad man dining alone, in the centre-right, is gunmaker James Purdey. (Picture credit: Charlie Jacoby, The East India Club: A History (London: East India Club, 2009), p. 61.)

The Managing Committee originally leased the old Crockford’s building from its owner, financier Julius Beer and his partner Mr. Lawson, for some £4,000 a year, alongside the adjoining building of 7-8 Bennet Street.

In 1876, with the members already complaining of a lack of space, the Club was able to expand by taking a 75-year lease on the connecting building at the rear, 6-7 Arlington Street. They subsequently exercised an option to buy the freeholds of these properties for £14,000.

More importantly, the Club was able to buy the freehold of its main building at 50 St. James’s Street that year, for £100,000. The purchase of the freehold plunged the new Club into a serious financial crisis - the first of many, in what would be a recurring theme. The Club would nearly close due to financial pressures in 1894, 1905, 1930 and almost permanently after 1945.

The Evening Standard reported that when the building was being sold in the early 2010s:

“In the basement of 50 St James a tunnel was found, which the seller swore led to White's.

“A legal nightmare loomed if anyone found out. So, the entrance was secretly bricked up. Nothing has been said to this day. This might not be so fanciful as it sounds.

“A history of the Devonshire Club, published in 1919, discloses that, "tradition has it that from this cockpit a bolt-hole existed with an exit into an adjacent and convenient spot". Where more convenient that White's? Perhaps one brave member could totter downstairs and check?”

An overnight electrical fire in 1930 caused extensive damage, gutting out all of the members’ bedrooms. Amid a restructuring, 6-7 Arlington Street and 7-8 Bennet Street were sold, with the Club using the income to build 27 new bedrooms.

Abandoned politics

The Home Rule crisis of 1886 split the Liberal Party down the middle, between the ‘official’ Liberal Party (which favoured Home Rule for Ireland), and the Liberal Unionists (opposed to Home Rule), who initially went into alliance with the Conservatives, and ultimately merged with them. It also had a dramatic effect on each of the Liberal political clubs. At Brooks’s, where the Whig grandees were overwhelmingly Unionists, it ultimately led to ceasing to be a politically-aligned club. While the Reform Club remained affiliated to the Liberal Party until the 1930s, most party activity was through the Political Committee, and this ceased to be party-political from 1886, assuming more the character of a discussion group. The divide was least pronounced at the National Liberal Club - even though they did have high-profile resignations such as Hartington, the Club had only recently been set up, and it drew most of its membership from the radical wing of the party, which tended to support Home Rule.

At the Devonshire Club, Home Rule had a decisive effect. Many of the active membership were Liberal Unionists. In the Committee elections of 1886, Joseph Chamberlain stood, and came second, signalling a move for the Club rapidly became identified as the club of choice for Liberal Unionists. As the Liberal Unionists grew closer to the Conservatives over the next three decades, the Devonshire became more of a small-c conservative club. In 1915, the Club’s political endorsement of Liberal politics was formally abandoned.

The result of the abandonment of the political link was that it became overwhelmingly a club for businessmen - typically Tory by inclination, but less politically involved than members of the Carlton, Constitutional, Conservative or St. Stephen’s Clubs.

The war years

The Club suffered bomb damage during the Blitz, adding to its financial prolems. Like many clubs in wartime, it also suffered from a falling-off usage of the club, with younger members called up and older members retreating to the countryside. And few wanted to lodge in central London bedrooms while the risk of bombing continued. Catering declined significantly amidst food rationing.

You can read about the story of Winston Churchill at the Club in World War II here, including how two Churchill portraits came to be commissioned by the Club - one of which hangs in the Smoking Room of the East India Club today.

The main staircase of the Devonshire Club, pictured in the 1940s. The portrait on the right is of Ormond Blyth, the Club’s wartime Chairman. (Picture credit: Tom Clarke, The Devonshire Club (London: Devonshire Club, 1943); colourised using the Kolorize.CC app.)

Post-war decline and closure

The Devonshire Club limped on with some difficulty in the post-war years. It had barely balanced the books in the inter-war years; but the post-war years saw large deficits. There were also disputes around staff pay, although they were partly ameliorated in 1962 when the Devonshire became the first of London’s historic clubs to allow tipping, with an optional 10% service charge added to bills.

In these later years, its signature dishes were Sole Colbert, and Omelette Surprise.

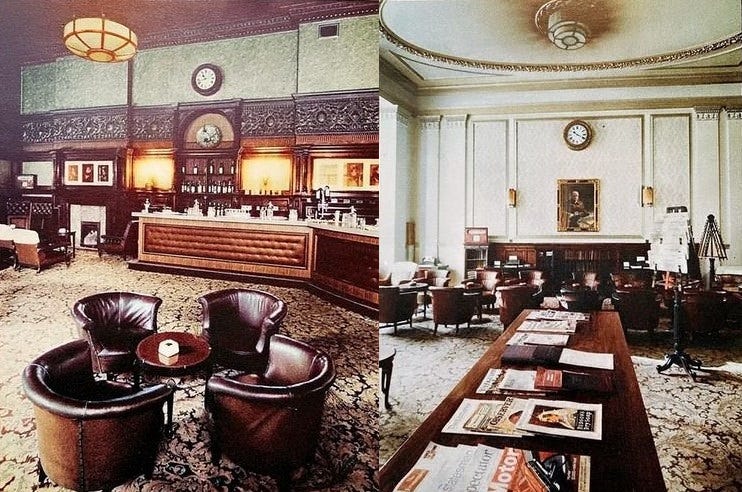

Two colourised images, of the Bar and South Smoking Room of the Devonshire Club, photographed in the 1970s. Note the Churchill portrait visible in the South Smoking Room. (Picture credit: Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen’s Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1979), pp. 104-107; colourised using the Kolorize.CC app.)

Anthony Lejeune noted that:

“Various expedients and mergers were proposed during a series of acrimonious General Meetings under the embarrassed Chairmanship of the [11th] Duke of Devonshire”

Denys Forrest recounted one scheme which sought to revitalise the Club, but also changed its character:

“In April 1965, the decision was taken completely to redecorate four rooms, christen them (with ducal approval) the Cavendish Suite and make them available for functions of all kinds. In practice, however, a group of Masonic Lodges took over…The Devonshire formed its own Lodge, the Arlington, in 1970.”

In 1967, the members voted by 685 to 36 to merge with the Naval & Military Club; but upon seeing the unusually strong accounts for the first half of the year, opinon shifted, and the Committee aborted the merger talks.

In 1975, the Devonshire Club’s members agreed to wind up the institution, voting by 434 to 17 to accept an offer for the freehold of the clubhouse. The building was sold that year to the government of Jamaica for £1.75 million (the equivalent of some £14 million today). Over the next few months, the Devonshire Club’s members moved temporarily into the Constitutional Club, then at 86 St. James’s Street, while they decided what to do next. An approach from the East India Club led them to formally merge the following year, narrowly achieving the nexessary two-thirds majority in a ballot of members. The East India Club’s historian Charlie Jacoby notes:

“After paying their debts, they brought a £1.37 million dowry with them as a long-term loan based, for tax purposes, on all Devonshire Club members joining the East India Club and all East India Club members becoming members of the Devonshire Club.”

Under the deal for the £1.37 million dowry, Devonshire Club members were able to claim one-third off the price of their food and wine bills at the East India Club, for the remainder of their lifetimes. Jacoby notes:

“In 2007 there were still more than sixty Devonshire members able to claim this boon, which is a testament to the success of an unusual and risky ‘deal’.”

A Devonshire Club which operated on Devonshire Square from 2016 until 2020 has no relation to the original Club.

The building since closure

The building remained in use as the Jamaican High Commission for two decades. From 1999 to 2009, it then operated as a casino, Fifty St. James’s Street, owned by restauranteur Robert Earl. Its licence was not renewed beyond 2009; amongst those objecting to renewal was White’s, whose members alleged in a submission to the Council on behalf of the Club that those frequenting Fifty St. James’s Street opposite sometimes engaged in visibly drunken behaviour and public urination.

In 2011, Quintessentially co-founder and property developer Luca Del Bono announced that he had secured the freehold of the building, on behalf of “anonymous Russian partners.” The Evening Standard reported:

“No, he won't say who they are. But he does say they are rich enough to have tried to buy Harrods”

Property developer Luca Del Bono pictured in the lobby of the former Devonshire Club building. (Picture credit: Knight Frank.)

Westminster City Council approved plans for the building’s new owners to redevelop it into a private members' club, with a public-facing spa, 14-bedroom hotel, and two restaurants. Spear’s Magazine enthused that:

“The rooftop terrace will be the place to be and be seen in 2012. Now’s the time to start angling for membership…”

Architect’s sketches submitted to Westminster City Council for the proposed new private members’ club at 50 St. James’s Street. (Picture credit: Westminster City Council website.)

But these plans did not come to pass. Land registry records show that the sale of the freehold did not proceed until 12 October 2012, when the building sold for £70 million. In 2014, it was revealed that the Russian owner, whose purchase Del Bono had engineered, was billionaire Andrey Goncharenko, the former CEO of a Gazprom subsidiary. There is no record of any further sale since then. The building has remained boarded up through the last 16 years, but with visible building work being periodically undertaken, including as recently as last year, when the long-term scaffolding came down. While there has been speculation that the building was due for conversion into a private home or a series of luxury apartments, Westminster City Council does not seem to show any sign of such plans ever having been formally submitted.

Further reading

Tom Clarke, The Devonshire Club (London: Devonshire Club, 1943).

Denys Forrest, Foursome in St. James’s: The Story of the East India, Devonshire, Sports and Public Schools Club (London: East India Club, 1982).

Charles Graves, Leather Armchairs: The Chivas Regal Book of London Clubs (London: Cassell, 1963), pp. 107-109.

Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen’s Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1979), pp. 104-107.

Henry Turner Waddy, The Devonshire Club and “Crockford’s” (London: Eveleigh Nash, 1919).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.