Crockford’s was a gambling club which existed for barely more than 20 years in several incarnations, but which cast a long shadow, in an age when London clubs were still in their infancy.

William Crockford, drawn by Thomas Howell Jones. (Picture credit: National Portrait Gallery).

The Club’s founder and proprietor, William Crockford, was born in 1776, the son of a Temple Bar fishmonger. The son also began his working life as a fishmonger (leading to his club’s later moniker “Fishmonger’s Hall”), but moved from supply to hospitality, particularly in establishments that hosted gambling.

Crockford went on to be the manager of Watier’s, a gambling club at 81 Piccadilly from 1807-19. The profits from this enterprise were highly lucrative, and enabled him to purchase number 50 St. James’s Street, almost directly opposite White’s. He was also influenced by some disputes in another St. James’s gambling house he frequented, at 5-6 King Street, and his wanting to exercise greater control in mediating such arguments.

George Cruikshank, Exterior of Fish-monger’s Hall'; a regular breakdown (1824) shows the original appearance of the clubhouse on St. James’s Street, with fashionable members inside and out.

As its name suggested, the new Crockford’s was a proprietary club, like many other clubs of the era such as White’s, Boodle’s and Brooks’s; it existed primarily to turn a profit for its owner. While the position of members was precarious and entirely at the whim of the owner, the club’s appeal lay in its being a fashionable place to be seen. In this respect, it also resembled the nearby Salons of St. James’s, where habitués had a similarly precarious status.

Henry Lutterell published in 1827 Crockford House, a Rhapsody in Two Cantos, which was satirical yet affectionate in its description of this chic environment:

‘Midnight sounds! - ‘Tis twelve o’clock!

See, like pigeons, how they flock

From the opera, or the play,

Or from t’other side the way,

Some, when gossip scarce requites

Those who linger there, from White’s;

Others, little to the cook’s ease,

From The Traveller’s or Brooks’s.

Pleased they ply the four-pronged fork,

Pleased they free the fettered cork,

Where, in rich abundance stored,

Every dainty crowns the board,

Heaped together, to entice

Squeamish tastes, at any price.

Games played in the club included faro, macao, lansquenet, and the highly fashionable (and often ruinously expensive) game of hazard.

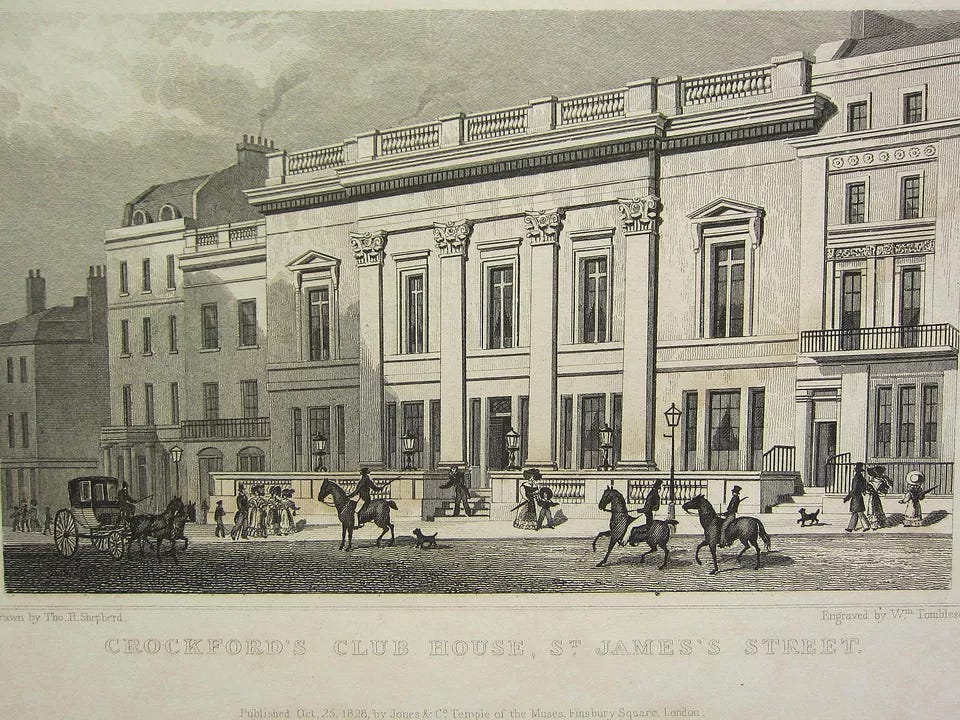

The club flourished, and by 1827 had acquired the neighbouring buildings at 51-53 St. James’s Street, rebuilding them in 1828 into a palatial new clubhouse. It boasted such amenities as an ice-house - a luxury in the era before refrigeration.

Crockford’s, with the facade reconstructed upon the acquisition of 51-53 St. James’s Street, neighbouring the original house at number 50. Thomas H. Shepperd. Crockford’s Club House, St. James’s Street (1828), engraved by William Tombleson.

Among William Crockford’s savvy decisions was the engagement of celebrity chef, Louis-Eustache Ude. Ude was best known for The French Cook Book (1812), and having been the founding chef of the United Service Club, he had also been private chef to George III’s son, the Duke of York. Upon the Duke’s death in 1827, Crockford enticed Ude to his club at the enormous salary of £1,200 - the equivalent of over £1 million today. His signature dish was mackarel roe paté. Upon Ude’s retirement, Crockford hired another celebrity French chef, Charles Elmé Francatelli, who would leave Crockford’s after two years to become head chef to Queen Victoria.

Cruikshank portrayed the interior, with the emphasis on unfair gambling with loaded dice. Isaac Robert Cruikshank, The Interior of Modern Hell, vide the Cogged Dice, from the English Spy (1825).

The Club flourished in the wake of breathless newspaper publicity about its members and guests. Theodore Hook, John Wilson Croker, Captain Rees Howell Gronow, Alfred Comte D’Orsay, Horace Twiss, Charles Greville, the 3rd Marquess of Waterford, the 3rd Marquess of Downshire, Sir George Warrender, Lord William Lennox, Grantley Berkeley, William Maginn, the 2nd Baron Alvanley and the young Benjamin Disraeli, all featured prominently in press coverage. They were a motley and eclectic mix of young politicians, writers, adventurers, hardened gamblers, and ageing hangers-on of Beau Brummel from the 1800s. But the members also included pillars of the establishment, such as the Duke of Wellington, who was Prime Minister by the late 1820s.

By the 1830s, Crockford tried to promote the idea of changing the establishment’s name to the St. James’s Club, but the moniker never caught on, and it remained Crockford’s to its members.

Joseph Grego, ‘Play at Crockford's Club, 1843, Count d'Orsay calling a Main’, illustration for Rees Howell Gronow, The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow being Anecdotes of the Camp, Court, Clubs, and Society 1810-60 (London: John C Nimmo, 1892). (Picture credit: World4.eu blog.)

Crockford himself retired in 1840 from the day-to-day management of the Club, but continued to be its proprietor, living in some prosperity at 11 Carlton House Terrace (later Gladstone’s house, and now home to the British Academy). He lost a substantial share of his fortune through unwise investments, but still lived in some style. He died in 1844. Contemporary accounts stressed that the Club struggled with his passing, but there are conflicting accounts of when it finally shut its doors - 1843, 1844, 1845 and 1846 are all given by different sources. What is clear is that the house passed through several different managers, who ran it erratically in these later years.

A minute signed by the Committee, dated 18th May 1844 - exactly one week before Crockford’s death - resolved:

“In consequence of several members persisting to use the Club without paying their subscriptions, as well as smoking at the door in defiance of the resolutions of the Committee, the Committee feel it to be their duty to place the management of the Club in other hands and respectfully to request this meeting to appoint their successors without delay.”

The London Gazette confirmed that the Club finally closed on 1 January 1846.

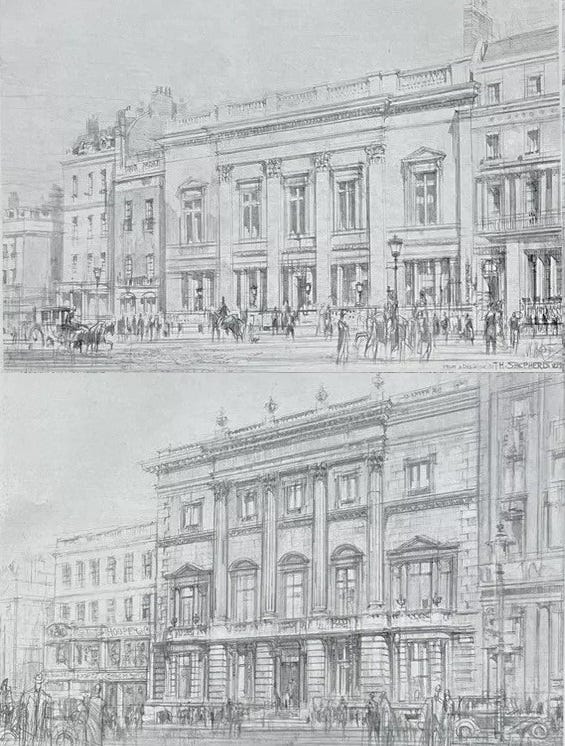

The building had a peripatetic existence over the next few years, including being used by one other club - the short-lived Military, Naval and County Service Club from 1848-51 - until it was rebuilt in 1874 into an expanded clubhouse. This was to accommodate a political club founded for Liberals, the Devonshire Club, which remained in the building until its own closure in 1976.

Illustrations from William Walcott for The Builder (1933), showing both the old Crockford’s building at 50-53 St. James’ Street, pictured in 1840, and the Devonshire Club building erected on its site, pictured in 1933.

Since then, the Crockford’s name was resuscitated by an (unrelated) gambling club, looking to convey the spirit of its illustrious forebear. (Although that did not stop it from claiming in recent years to be “est. 1828.”)

This “new” Crockford’s was initially based at 21 Hertford Street when it opened in 1928, moving more permanently in 1934 to 16 Carlton House Terrace, where it remained until 1982, when it was embroiled in the Metropolitan Police’s crackdown on casinos. It reopened later that year, under new management, at 30 Curzon Street, where it remained until its closure in 2023. A sign on the door of the last premises informs passers-by that they have since moved in with the Colony Club, a casino at 24 Hertford Street.

Sign on the door of 30 Curzon Street, seen from the street, photographed earlier this year.

For such a short-lived club, the original Crockford’s has enjoyed a surprising amount of attention. Henry Lutterell, the author of the ballad quoted above, wrote a substantial two-volume book on the club in 1828, examining it as a social phenomenon; the Devonshire Club’s 1919 history included an extended section on Crockford’s; while in 1953, A. L. Humphreys published an extended social history of the vanished club. Crockford’s foreshadowed a number of popular proprietary clubs of the 20th and 21st centuries, which carefully cultivated a well-known membership and public image to become highly profitable enterprises for their owners.

Further reading

A. L. Humphreys, Crockford’s; or, The Goddess of Chance in St. James’s Street, 1828-1844 (London: Hutchinson, 1953).

Henry Lutterell, Crockford’s: or, Life in the West, 2 vols. (London: J & J Harper, 1828).

Henry Turner Waddy, The Devonshire Club and “Crockford’s” (London: Eveleigh Nash, 1919).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.