Winston Churchill and His Clubs

As a “thank you” to my paying subscribers, I am providing them with an updated version of my article on the club memberships of Winston Churchill, which was first published last year.

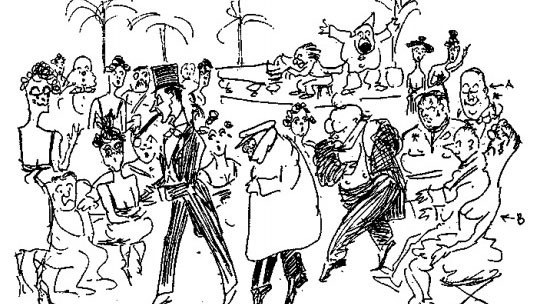

A 1917 cartoon of the members of the Other Club leaving the Savoy, including Winston Churchill. (Picture credit: Colin Coote, The Other Club (London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1971).)

Mention Winston Churchill in connection with clubs, and the Other Club invariably comes to mind. This dining society, co-founded with F. E Smith at the height of partisan rancour in 1911 against a backdrop of constitutional turmoil, harked back to the earliest informal dining clubs of the eighteenth century, most notably “the Club” founded by Samuel Johnson and Joshua Reynolds—from which Churchill himself had been blackballed. The Other Club reflected the same cross-party composition that defined many of those early clubs and was reflected in establishments such as the Travellers Club and the Athenӕum. Yet the Other Club does not fully capture Churchill’s lifelong participation in Clubland.

Churchill was born into the Victorian political system, which had clubs at its very heart. The great fire of 1834 had meant that during the thirty-five-year construction of the present parliamentary estate, parliamentarians avoided the building site and sought exile in their clubs, from which the country was run and resulting in the term “club government.” Also in the 1830s, political clubs such as the Carlton Club for Conservatives and the Reform Club for Liberals acted as political headquarters. By the mid-nineteenth century at least 95% of MPs belonged to at least one club and typically two or three.1 To this day, fifty-six of the fifty-eight British Prime Ministers have belonged to a London club.2 Churchill belonged to fifteen —more than any other. By the 1890s, London’s West End had around 400 clubs. Some were purely social, while others based themselves on military, literary, and scientific fields or around shared occupations, interests, or educational background. The British exported clubs across the empire too, as these institutions provided a social and political centre for the ruling elite while supplying many of the creature comforts of home.

Lord Randolph Churchill was a keen participant in this club system, from political clubs such as the Carlton, to gambling clubs such as the St. James’s. It is no surprise that his son followed suit. Winston Churchill’s first club was an imperial one, which he joined while on active service in India in the late 1890s. This was the United Service Club of Bangalore (renamed the Bangalore Club upon Indian independence in 1946). The USC was the premier military club in what was then a garrison city of southern India. It was set in fifteen acres of grounds and followed the “gymkhana” model of many Indian clubs, blending the social and literary facilities of a London club with the sporting facilities of a country club. Although there are no surviving records of Churchill either joining or resigning—many Indian clubs suffer from poor retention of paper records mouldered away in humid climates—there is one piece of evidence that proves Churchill’s membership: an unpaid thirteen-rupee bar tab. Incurred by “Lieutenant W. L. S. Churchill” and recorded on 1 June 1899 in a contemporary ledger book shortly after his final departure from India, it is today on display in the club’s front lobby.3

The 1899 ledger book, still on display in the Bangalore Club lobby today, showing Winston Churchill’s unpaid 13 rupee bar tab.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Seth Thévoz’s Clubland Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.