My recent post on the Junior Carlton Club on Pall Mall prompted several readers to ask me about its namesake, the Carlton Club.

Its current building gives an impression of solidity and history, and indeed it is one of the historic sites of Clubland, being the former site of White’s (from 1698-1733 and 1736-78), including when it reopened as a club for the first time, in 1736. But it did not host the Carlton Club until 1943.

This post shines a light on the Carlton Club’s former buildings - only one of which survives today.

The changing sites of the Carlton Club since the 1830s. (Picture credit: base map from Google Maps.)

The Carlton Club generally gives 1832 as its foundation date, with a meeting in the Thatched House Tavern of St. James’s Street on 10th March which officially constituted it. Yet (fittingly for a conservative club) it had already organically evolved in the year or so before that. The period 1830-2 saw stormy debates over successive Reform Bills. The Tory whips and election managers who were trying to stymy and avert reform met in the house of Joseph Planta MP at 10 Charles Street (since renamed Charles II Street), just off St. James’s Square - and they became known as “the Charles Street Gang.” The bane of their existence was the presence of various eager conservatives who would come in for gossip, expecting refreshment, distracting them whilst there was practical work to be done. By 1831, Planta had vacated his house, turning it over to his Tory opposition colleagues for official use, but this did little to quell the appetite for it to serve a social as well as political function.

The entrances to numbers 1, 2 and 3 Carlton House Terrace, which were completed in 1831, pictured in 2019. Number 2 had been the first clubhouse of the Carlton Club, from 1832-5. (Photo credit: Google Maps street view.)

The solution was the creation of a formal Tory club in 1832, presided over by the Tory leader, the 1st Duke of Wellington, and with its political functions carried out by solicitors in separate offices, under the supervision of Tory whips, beginning with Francis R. Bonham. The Carlton’s initial home still stands today, at 2 Carlton House Terrace (and is currently the headquarters of asset management firm Carmignac UK Ltd).

The former Royal palace of Carlton House, superimposed over an 1894 Land Registry map of the surrounding district. 2 Carlton House Terrace can be seen in the bottom-left quadrant, as can the later Carlton Club site north of it. (Picture credit: Hugh Tait and Richard Walker, The Athenæum Collection (London: Athenæum, 2000), p. xvix.)

The building was brand new at the time, having only been completed in 1831. Its location provided the Club with its name, based on occupying the grounds of Carlton House, the former home of the Prince of Wales who subsequently became George IV. (It also provided the Carlton with its heraldic badge, which is based on that of the Prince of Wales, “a plume of three ostrich feathers Argent enfiled by a royal coronet of alternate crosses and fleur-de-lys Or.” The Carlton does not use the Prince of Wales’ motto Ich dien [“I serve”]; although by special agreement, the Junior Carlton did so on its crest, which was almost identical to the Carlton’s.) Carlton House had been demolished in 1827-9. The premises on Carlton House Terrace were leased from 1832 until 1835, when the Club was evicted over a rental dispute with its landlord, the independent-minded 2nd Baron Kensington. In the ensuing months, the Club occupied a suite of rooms in the Carlton Hotel on Waterloo Place (now long since demolished), while it awaited completion of its first purpose-built clubhouse, upon which building work had commenced in November 1833.

The Carlton’s newly-completed second clubhouse of 1836 - its first purpose-built one - can be seen on the far right of this view down Pall Mall. Although the illustration was published in 1837, this view was already changing by January of that year, when demolition started on the three neighbouring townhouses to the left of the Carlton. These three modest buildings, temporarily housing the Reform Club, would be replaced by the present Reform Club clubhouse, constructed in 1838-41. (Picture credit: Anonymous artist, ‘Pall Mall: Looking west down Pall Mall, with the Carlton and other club premises’, Penny Magazine, 1837.)

When this building opened at 94 Pall Mall early in 1836, it was considered highly fashionable, to a Palladian design by Sir Robert Smirke, which was built by Bennett & Hunt of Horseferry Road. It followed the trend of recent clubhouses such as Smirke’s own Union Club building completed in 1827 (now the Canadian High Commission), John Nash’s United Service Club in 1828 (with later re-facing by Decimus Burton, which is now the Institute of Directors), Decimus Burton’s Athenæum in 1830, and Charles Barry’s Travellers Club in 1832.

The Carlton as part of the vista of neighbouring clubhouses along the south side of Pall Mall by the 1840s. From right to left: Carlton Club, Reform Club, Travellers Club, Athenæum, and United Service Club. Note that by the time of this picture, a few short years after the previous one, the Carlton had gone from overshadowing the old Reform Club building, to being overshadowed by the new one. (Picture credit: Anonymous artist [after Thomas Shotter Boys], The Clubhouses of Pall Mall, 1840s.)

This Carlton building had its admirers. Benjamin Disraeli, then a newly-elected Tory MP who had already been blackballed from the Athenæum, Grillion’s and the Travellers Club (and had been ejected from the Westminster Reform Club over non-payment of his subscription), was extremely impressed with it. He wrote to his sister Sarah from the new clubhouse on 16 April 1836: “‘The Carlton is a great loun[ge]. I write this in the room [where there are] some 80 persons all of the first importance.” His letters show that he was a frequent presence in the drawing room during the parliamentary session, sending out letters on headed notepaper, often with asides about the people he spotted around the place.

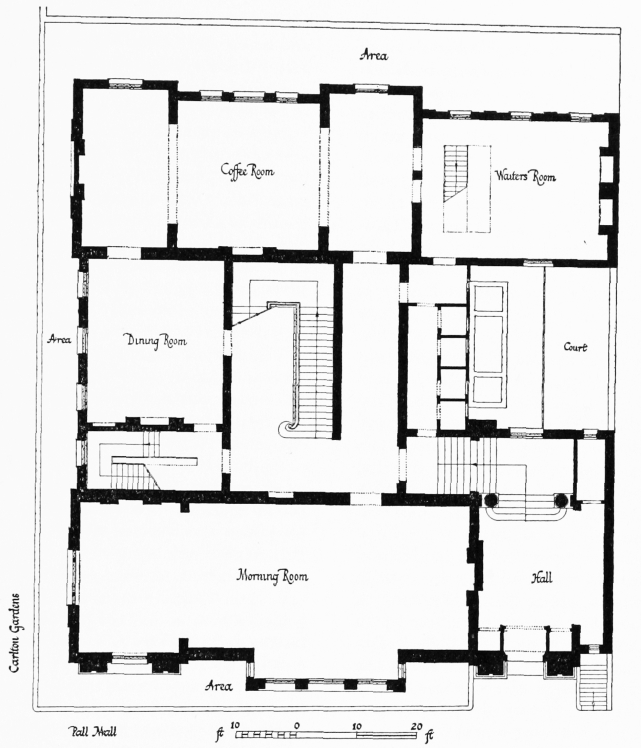

Plan of Robert Smirke’s clubhouse for the Carlton Club, constructed 1833-6 & in use from 1836-54. (Picture credit: F. H. W. Sheppard, Survey of London: Vols 29-30, St James Westminster, Part 1 (London: London County Council, London, 1960), p. 355.)

However, the building did not age well. F. H. W. Sheppard believed, “The plan was undistinguished, merely a reasonable arrangement of rooms around a central staircase.” A number of design flaws soon became apparent, not least the highly inefficient use of space, which necessitated a circuitous route around the clubhouse. Additionally, the period 1838-41 saw the construction, literally next door across the side alleyway of Carlton Gardens, of the rival Reform Club by Charles Barry, for Reformer and Liberal MPs. The Reform Club was - and remains - one of the most opulent clubhouses ever built, and it was a source of some embarrassment for the Carlton to be outdone in this way by its immediate neighbour and adversary. Consequently, within a few years of completion, the Carlton’s members were openly contemplating replacing their own building, and by 1842 the Committee had already voted to put out tenders for a bigger building.

Indeed, the location of the two rival political parties’ clubhouses side by side made for some friction, even in these earliest days. For instance, a day after the 4th Earl of Aberdeen formed his Peelite coalition government (which was something of a precursor to the later Victorian Liberal Party, counting on the support of Whigs and Peelites), Gladstone returned to the Carlton Club on the evening of 20 December 1852. Like many Peelites of the early 1850s, Gladstone viewed himself as a ‘true’ Conservative, and initially retained his membership of the Carlton Club. Earlier that evening, the Carlton had hosted a dinner for some 20 MPs to celebrate the acquittal of Conservative whip William Beresford on corruption charges. In the Club’s first-floor Library facing Carlton Gardens, a group of Conservative MPs grew increasingly angry with Gladstone, who had just accepted office as Chancellor in Aberdeen’s coalition, and they threatened to throw him out of the window, in the direction of the Reform Club opposite, where they suggested he really belonged. (Gladstone, who quietly resigned his Carlton membership in 1859, did eventually accept membership of the Reform Club on becoming Liberal Prime Minister in 1868; but he seldom used the latter, and lapsed his Reform Club membership at the end of his first term as Prime Minister in 1874. The two clubs he used most heavily were the United University Club, and the Carlton.)

The Carlton Club’s second Pall Mall clubhouse, built on the site of its previous clubhouse in 1854-6. Note that beyond it can be seen Cumberland House, then hosting the Ordnance Office and (from 1858) the War Office, until its demolition to make way for the current Royal Automobile Club. (Photo credit: Leonard Bentley, flickr.)

Sydney Smirke (younger brother of Sir Robert) was commissioned as the new architect in 1845. Having just completed in 1844 the new St. James’s Street clubhouse for the offshoot Conservative Club (the front section of whose building still survives) in collaboration with George Basevi, Smirke and Basevi had submitted plans together, but the Carlton decided they only wanted to engage Smirke.

Plan of Sydney Smirke’s clubhouse for the Carlton Club, constructed 1854-6 & in use from 1856-1940; though considerably altered in 1923-4. (Picture credit: F. H. W. Sheppard, Survey of London: Vols 29-30, St James Westminster, Part 1 (London: London County Council, London, 1960), p. 358.)

Construction of the new clubhouse eventually took place in two stages. The first involved the western wing in 1846-8. The second, larger construction took place from 1854-6, so that the Carlton was never entirely closed to its own members. Instead, when it came to demolishing the majority of the existing clubhouse, there was already a segment of completed clubhouse which could be used.

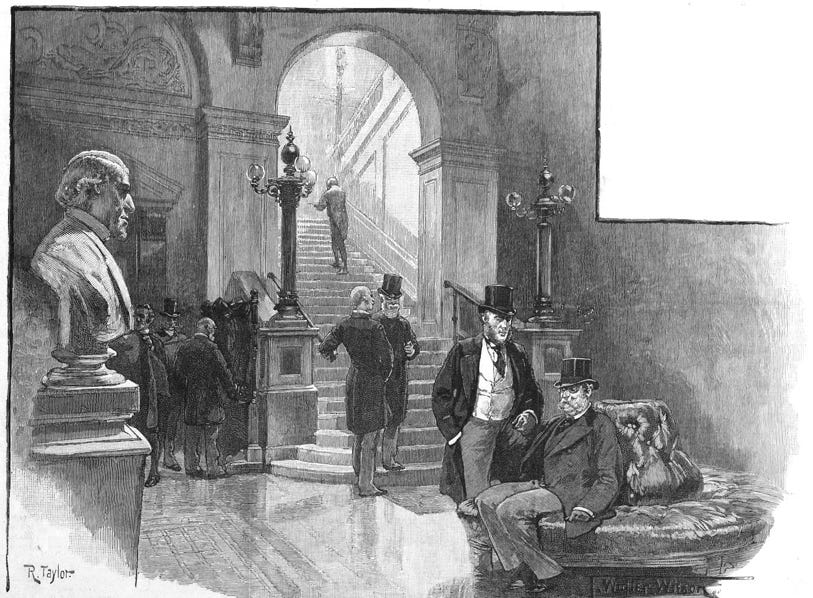

The central vestibule of the Carlton Club in the 1890s. (Picture credit: Illustrated London News, 24 May 1890, p. 649.)

Just as Charles Barry’s rival Reform Club drew an Italianate influence (the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, completed by Michelangelo), the detailing on the Carlton’s façade was inspired by Jacopo Sansovino’s Marciana Library (aka Petrarch’s Library) on St. Mark’s Square, Venice.

The Coffee Room (dining room) of the Carlton Club, pictured in 1900. (Photo credit: Sir Wemys Reid, ‘In Club-Land’ in George R. Sims (ed.), Living London: Its Work and Its Play, Its Humour and Its Pathos, Vol. 1 (London: Cassell, 1901), p. 76.)

This building was to stand until 1940 (although it underwent a major refit and refacing in 1923-4). It closely mirrored the floorplan of the rival Reform Club, with its large, central atrium, and first-floor galleries for looking down on arrivals and departures. Like the previous building, it had dedicated offices for Conservative agents and whips in the basement. Its Library, while not as extensive as that of the Athenæum, was easily the rival of the Reform Club’s - which was the intention. And the Club remained largely unchanged for the next seven decades, save for the London pollution heavily staining the porous Caen stone of the exterior. When Victorians and Edwardians spoke of “the Carlton Club”, it was this building which was meant.

The Carlton Club at 94 Pall Mall, pictured in 1885, as photographed by James Valentine. The caption’s reference to it as the ‘Senior‘ Carlton Club is because by this time, it diagonally faced the Junior Carlton Club on the north side of the street (Photo credit: History of Photography Archive, flickr.)

It was still this clubhouse - heavily blackened by soot and pollution, and with a crumbling façade visible in a contemporary newsreel - which hosted the fateful Carlton Club meeting of 19 October 1922, arguably the most famous political meeting in Clubland history. The meeting - which I describe more fully in the updated new paperback edition of my book Behind Closed Doors - was responsible for Conservative MPs bringing down the Conservative-Liberal coalition government led by David Lloyd George.

Originally designed as the Library on the first floor, this room of the Carlton Club was in use as its Smoking Room by the 1890s. (Photo credit: Illustrated London News, 1896) An 1890 Illustrated London News illustration of the same view, populated with Unionist politicians of the day, can be seen on the Carlton Club website here.

Only a few months after the 1922 meeting, the Club had a heavy refit. Gone was the crumbling Caen stone exterior. A new Portland stone shell designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield was constructed in 1923-4, providing a protective cocoon for the interior, and conforming to the contemporary architectural trends of the day - it resembled more of a Whitehall ministry than a Victorian clubhouse, which was perhaps appropriate for such a political club.

Sir Reginald Blomfield’s 1923-4 alterations to the façade of the Carlton Club, pictured in 1927. (Photo credit: London Town, Described and Illustrated (London: Homeland Association, 1927).)

Blomfield was a leading architect of the day, who had already had some experience of updating ageing clubhouses. He had upgraded the facilities of the Oxford & Cambridge Club between 1906-12 (including the design of its current staircase), and his periodic alterations to the United University Club building of 1906, 1924 and 1938 mirrored his work on the Carlton: instead of demolishing a crumbling Palladian clubhouse, he encased it in a new exterior. (Blomfield’s 1924 exterior to the United University Club on Pall Mall East, now Fischer Hall of the University of Notre Dame’s London Campus, bears some comparison to his work on the Carlton, above.) It was this final 1920s iteration of the Carlton Club which stood for the remainder of the inter-war years, and which suffered a direct hit during the Blitz of 1940.

In 1925, the Club also gained an Annexe, behind the main clubhouse, at 7 Carlton Gardens. This was primarily given over to bedroom accommodation for members, although it also came with an additional dining room which allowed members to entertain female guests - something not permitted in the Carlton’s main clubhouse. While the Annexe itself was not hit during the Blitz, it was gutted by fire which spread from the nearby Carlton building on the night it was bombed, and rendered unuseable; the Club gave up the lease on it in 1941.

I will probably cover the Carlton’s bombing in a future standalone post - provided I don’t overlap too heavily with the description given in Behind Closed Doors - but it’s worth acknowledging that although the Carlton suffered a direct hit and its contents collapsed in the bombing, the freestanding, hollowed-out walls of the empty building remained on the site until the early 1960s.

A small point - Sydney Smirke’s building was of Caen stone, which was used in spite of warnings that it did not respond well to the London atmosphere (as the East front of Buckingham Palace was to demonstrate). The more resistant Portland stone was used in Blomfield’s refacing of 1924.