The former United University Club building, photographed in 2021 from the Pall Mall side, embedding the 1906-7 alterations by Reginald Blomfield. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Foundation.)

The United University Club was Britain’s first club themed around education. Founded in 1821, it was among the first wave of middle-class clubs of the early 19th century (as opposed to the aristocratic social clubs of the 18th century), focussed around professions and shared interests.

The original clubhouse, as illustrated in John Timbs, Clubs and Club Life in London, with Anecdotes of its Famous Coffee Houses, Hostelries, and Taverns from the Seventeenth Century to the Present Time (London: Chatto and Windus, 1866).

Origins

The Club was formed at a meeting in the Thatched House Tavern on 30 June 1821, with a resolution which stipulated that it would be limited to 1,000 members who were graduates of Oxford or Cambridge Universities - a limit that was soon raised. Resident undergraduates were explicitly barred from membership - this was a club for alumni and dons. Its inaugural Annual General Meeting was held on 27 April 1822 in Willis’s Rooms on King Street, St. James’s.

At the time, Oxford and Cambridge were the only universities operating in England, though in the ensuing decade, there would be a flurry of new educational establishments engaged in university teaching, from Durham to London. Thus although the Scottish universities educated many notable figures of the era, Oxbridge retained a stranglehold on English university education.

That said, the original incarnation of the Club can be seen as more ‘establishment’ than ‘academic’ - prior to the mid-19th century reforms to the Tripos, neither of these two universities was considered particularly academic. Aside from their significance in training of Anglican clergy (which was as vocational as it was religious), they were primarily considered finishing schools for the wealthy, rather than yet being serious centres of research and teaching.

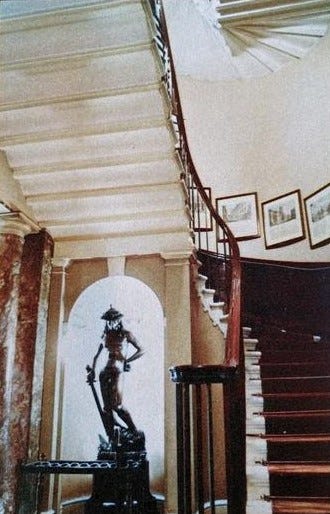

A colourised image of the somewhat cramped front staircase, photographed in the early 1970s. The statue - a bronze cast copy of Donatello’s David - has since been moved to the staircase of the Oxford & Cambridge Club. (Picture credit: Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen’s Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1979), pp. 104-107; colourised using the Kolorize.CC app.)

Membership

Within two years of the Club launching, the membership was already full, and a waiting list opened up - the Club remained oversubscribed until the First World War.

Club historian John Thole noted that its original membership comprised a combination of grandees, dons, politicians, school headmasters, and clergy. This last group actually made up the largest single occupational group in the club, with 284 of the original 1,000 members being clergymen - reflecting the universities’ deep involvement in the established church in the 1820s.

Thole highlighted the number of parliamentarians among the active membership in the early days. Of the 30 original trustees and committee members, 16 were sitting MPs. These:

included two past or future Chancellors of the Exchequer (the Marquess of Lansdowne and T. Rice Spring), a future Prime Minister (the Earl of Aberdeen) and the current Speaker of the House of Commons, Charles Manners-Sutton. The senior trustee was the Duke of Northumberland, who was to become the Chancellor of Cambridge in 1840, and was according to Greville ‘an eternal talker and a prodigious bore’.

Another member who joined in the early years early was William Ewart Gladstone, elected in 1832, who would remain a member until his death in 1898. Gladstone had many club memberships over his lifetime, but the United University Club was one of only two (along with the Carlton Club, prior to his defection to the Liberals) which he used particularly heavily. He was twice elected to the committee, once in 1837, and again in 1858, serving until 1861. Prior to 1865, Gladstone lived around the corner, at 10 Carlton House Terrace, less than a five-minute walk away from the clubhouse, so it was particularly convenient to him. Also convenient to him was the club stationery, which he stole in large quantities - something I found when working through the boxes of his private papers in Hawarden, containing reams of letterheaded club paper, both used and unused.

While the Club remained avowedly apolitical and cross-party, a rare early example of political activity was the ordering of lamps in 1832, for illuminations to celebrate the passage of the Reform Act.

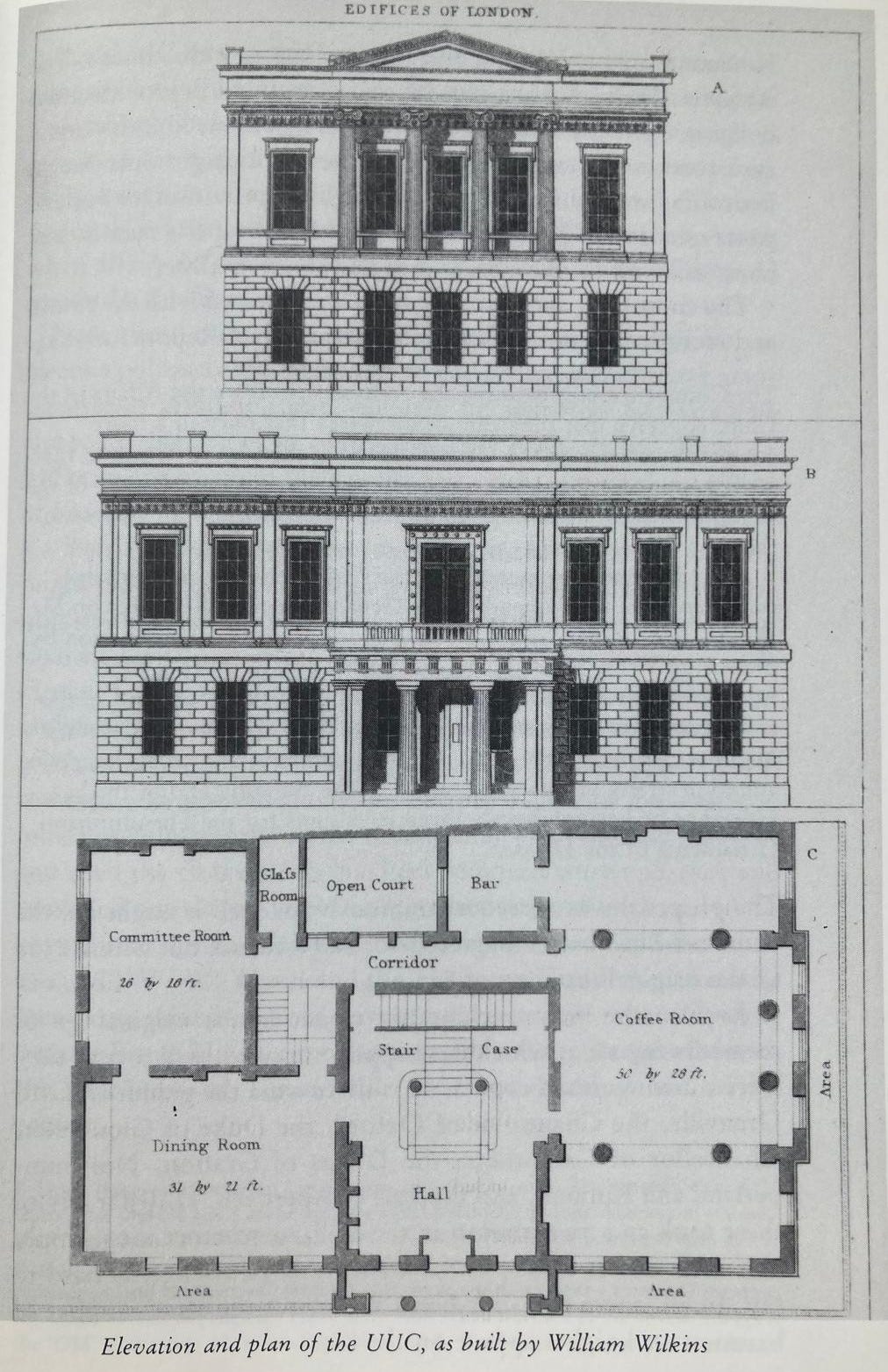

The original clubhouse by William Wilkins. (Picture credit: John Thole, The Oxford and Cambridge Clubs in London (Henley-on-Thames: Alfred Waller-United Oxford and Cambridge University Club, 1992), p. 5.)

The evolving clubhouse

The Club found a site at 1 Suffolk Street, on the corner with the north side of the eastern end of Pall Mall, close to what was then New Square (now Trafalgar Square). William Wilkins was commissioned as its architect, with assistance from John Peter Gandy. The building was completed in 1826.

Wilkins did not have any experience as an architect of clubs, but he had considerable experience as an architect of universities and schools, having designed and built Downing College, the first new Cambridge college in over 200 years. It was built in the Classical Greek Revival style with which Wilkins was most associated. He had also overhauled the Provost’s Lodge, hall, stone screen and bridge of King’s College in Cambridge, in a Gothic Revival style in keeping with King’s College Chapel. After his UUC, he would go on to design the King’s Court of Trinity College, Cambridge, the chapel and new court of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and University College, London.

For his United University Club building, he reverted to his Classical Greek Revival style, in a building which proved influential on both Decimus Burton’s Athenaeum and Robert Smirke’s Oxford & Cambridge Club, both further along Pall Mall and both still standing today.

While the room was capacious by the standards of early 19th century clubs, it was soon outpaced by other clubhouses amid the aggressive expansion of clubs later that century. By the 1870s, members were frequently complaining about the lack of any bedroom accommodation - something increasingly common in other clubs from the 1840s. In an attempt to ameliorate this, an extra storey was added in 1853, offering an extra billiard room, five new dressing rooms and eleven new staff bedrooms, including one for the Secretary - but there were still no bedrooms for members.

The UUC had long retained a Club Architect. From 1852 until his death in 1878, this was P. C. Hardwick, who was responsible for the extra storey. After his death, his former pupil Sir Arthur Blomfield assumed the title, but there was little he could do against the backdrop of a committee that was hostile to incurring new expenditures. After Sir Arthur’s death in 1899, the title passed to his nephew Sir Reginald Blomfield, and he was to oversee a major transformation of the Club.

Blomfield’s work on the Club in 1906-7 was extensive, and was undertaken with the blessing of the membership at a special general meeting. He provided the addition of a further storey - including the long-demanded bedrooms, which numbered ten for members. He rearranged the interior considerably, including moving the Coffee Room (dining room) from the ground floor to the first floor, while the ground floor was turned over to a succession of smoking rooms. And most obviously, he provided the building with an entirely new facade, more in keeping with Edwardian sensibilities.

So successful was Blomfield’s work, that he would establish a reputation of overhauling and modernising other clubs that had ageing infrastructure: in 1906-12, he heavily altered the Oxford & Cambridge Club, including constructing its present staircase; while in 1923-4, he modernised the Carlton Club’s then-building on Pall Mall, including completely refacing it with a new facade, in a similar style to his work on the United University Club.

Blomfield’s remodelled facade for the United University Club building, seen from the main entrance on Suffolk Street, photographed in 2025.

Offshoots

From the outset, the Club was oversubscribed, so that in 1828 when it was only seven years old, a breakaway club was mooted, the present-day Oxford & Cambridge Club, which opened at 71 Pall Mall in 1830.

The New University Club stood a few doors from Brooks’s at 57-58 St. James’s Street from 1864-1938, and will doubtless be the subject of a future ‘Lost Clubs’ feature, simply on account of its remarkable architecture (now sadly demolished).

From 1879-1892, there was also a Junior Oxford & Cambridge Club (technically an offshoot of an offshoot) at 8 St. James’s Square.

Finally, there was a New Oxford & Cambridge Club from 1885-1933, which was based at 66-68 Pall Mall for most of its existence.

The number of these offshoot clubs stands testament to the demand for a club explicitly catering to Oxbridge graduates in London - even though they were already disproportionately well-represented among the existing clubs.

The Nuffield studies

The Butler family of academics were also long-time members of the Club - something I came to realise when I was the research assistant on Michael Crick’s biography of the pioneering psephologist Sir David Butler. Butler had joined the Club in 1948, remaining a member until he resigned in 1995 in protest at the by-now-merged United Oxford & Cambridge Club’s then-refusal to admit women.

In conversation, I found him still very proud of his former membership of the Club, recounting that his great-grandfather George Butler had been one of its founder members. It was the centre of his conversations with ‘Establishment’ politicians in the 1950s and 1960s - the Nuffield election studies which he oversaw depended heavily on the informed insight gleaned with key players in all the political parties, everyone from “big beasts” on the front benches, to little-known backroom fixers and agents.

More often than not, when David Butler spoke to people in Westminster, his preferred approach was booking an appointment over a cup of coffee in the United University Club - something confirmed in Butler’s copious contemporaneous notes of these conversations, which are still held in Nuffield College. I am still restricted by various covenants around the archive from saying anything too specific about its contents, but I found it all very Yes, Minister in tone.

Decline, and merger with the Oxford & Cambridge Club

Like many comparable institutions, the United University Club experienced a long, slow decline through much of the 20th century. It had a welcome reprieve just prior to the Second World War, when the closure of the New University Club (see above) resulted in its absorption into the UUC, and a doubling of membership numbers to 1,700. After that, however, membership resumed its long decline. By 1954, the Club was losing £500 a month (nearly £20,000 today). By 1966, its overdraft was £20,000 (over £500,000 today).

As well as dwindling numbers, the Club also suffered from dwindling use, with many blaming the civil service (which accounted for many members) offering generously-subsidised canteens which made club lunches a less appealing choice. The Club also suffered from the same rising costs and inflation which hit much of Clubland. In desperation, the Club tried various approaches, including the sale of its silverware in 1965, a 1967 opening-up of membership to non-graduates, the sale of valuable old books in 1968, and a mooted merger with the University Women’s Club.

Finally, in 1971 came a torrent of events. The UUC’s committee had already been advised that it would be insolvent by the end of 1971, and would need to make plans for winding up by the end of the year, which it did so. But in the meantime, there were several key developments at the Oxford & Cambridge Club, which was in no less financial peril. The O&C had first voted in January 1971 to wind itself up, and then had that vote negated by a follow-up vote of members in May. There was thus the very real prospect of amalgamation between the United University Club and the Oxford & Cambridge Club.

Making this all the more feasible was that Coutts & Co were searching for a temporary new headquarters while their long-term home on the Strand was rebuilt, and let it be known that they were amenable to purchasing the UUC’s lease, which still had 28 years left to run on it.

A joint plan was therefore developed. Both clubs closed down by the end of 1971, and the newly-merged United Oxford & Cambridge Club was constituted at a committee meeting on 21 December 1971. The plan was to renegotiate and extend the Crown Estate lease on the Oxford & Cambridge Club building on Pall Mall, and to use the proceeds of selling the United University Club on Suffolk Street to renovate the dilapidated O&C building. The merged club therefore temporarily opened in the UUC’s old home on Suffolk Street on 7 March 1972, while extensve building work was undertaken on Pall Mall. Suffolk Street finally closed as a clubhouse on 9 February 1973, to meet the deadline for Coutts taking possession of the building. On 12 March, the renovated Pall Mall clubhouse first opened for members of the merged club - though it was not yet complete, and the ladies’ annexe was not open until April, and the first bedrooms not until October. The name of the merged club reverted to being the Oxford & Cambridge Club in 2001.

The clubhouse since 1973

The former clubhouse on Suffolk Street still stands, and has changed hands several times. In 1973, it was taken on by Coutts & Co, who used it as a temporary headquarters. In 1980, it was sold on to the British School of Osteopathy, who used it as their London headquarters. In 1998, they sold it to its present owners, the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, which uses the building as its London campus.

Further reading

Francesca Herrick, A Guide to the Art Collections of the Oxford and Cambridge Club (London: Oxford and Cambridge Club, 2012).

John Thole, The Oxford and Cambridge Clubs in London (Henley-on-Thames: Alfred Waller-United Oxford and Cambridge University Club, 1992).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

My uncle Anthony, a civil servant, was a member and told me a number of the UUC staff moved to the merged club. When I had tea with him at the O&C club c1974 he was offered, but declined, a cup of tea which appeared to have no tea in it. As my uncle was (over) fond of alcohol I have always assumed there was some gin in the cup. Surely the best sort of club servant, who knows members’ “special requirements “!