The fondly-remembered TV series Yes, Minister and its sequel Yes, Prime Minister often featured mandarin Sir Humphrey Appleby holding sotto voce off-the-record after-hours meetings in London private members’ clubs. Over the years, I’ve had quite a few questions on the portrayal of these clubs, and hope to shed some light on them here.

It is often made very clear when scenes in the series are set in a club, with the camera lingering on notices addressed to “Members.” We see at least 9 club rooms throughout Yes, Minister and Yes, Prime Minister; though they could have portrayed as few as 3 clubs. Which clubs are they meant to be?

The clubs in the books

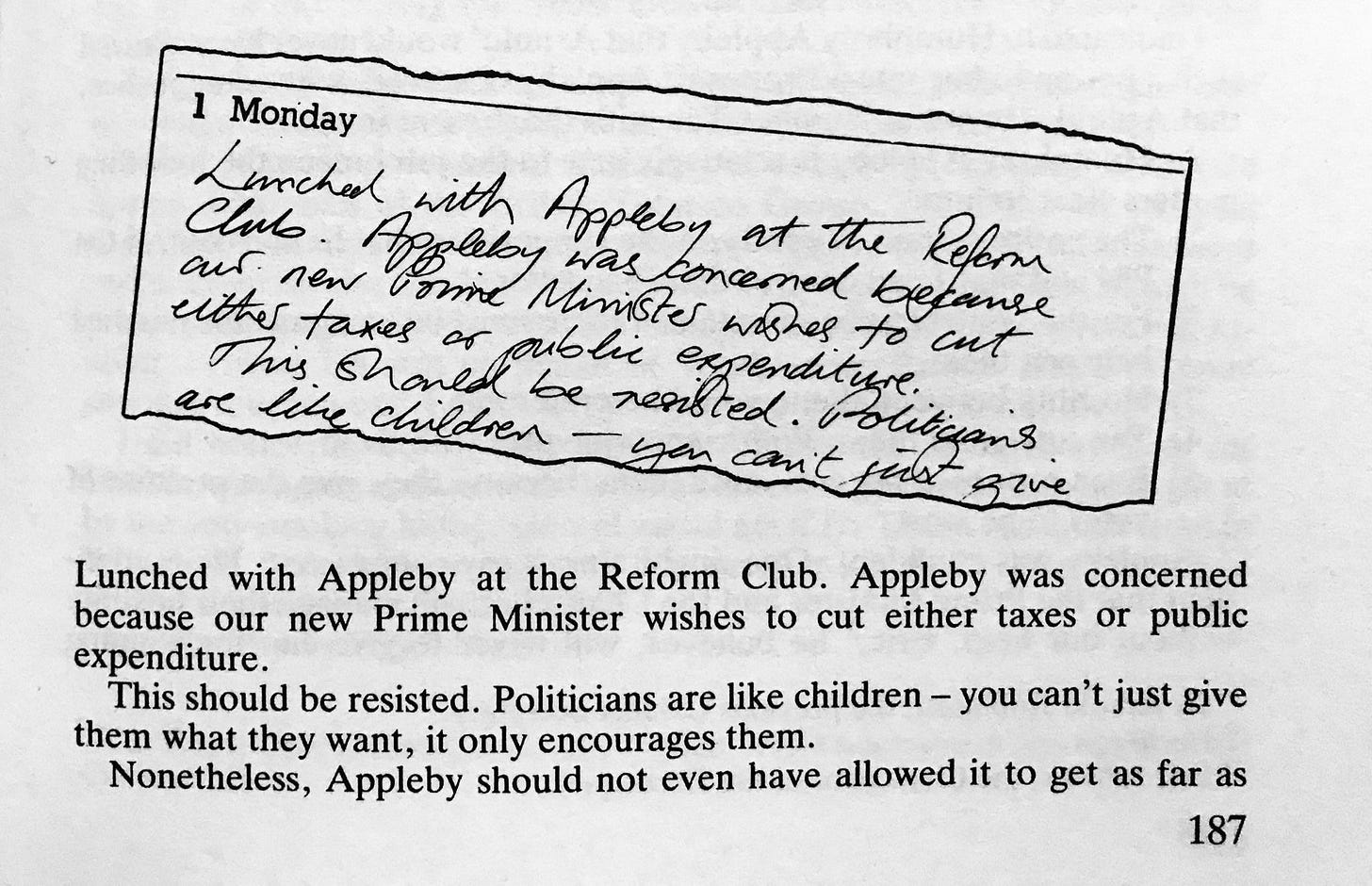

Each series was subsequently adapted into a book, formatted as cut-and-pasted extracts from the private diaries of the various characters. The books (or at least, the later books) are much clearer on the choice of clubs than the TV series: Sir Humphrey & Sir Arnold are both members of the Athenæum. That is explicitly stated throughout multiple diary entries, whenever they meet at “The Club”, with the Athenæum being described as “their old haunt.” This should come as no surprise, it has long been a popular club for Permanent Secretaries.

One of many references in the Yes, Prime Minister books to Sir Humphrey Appleby and Sir Arnold Robinson meeting at the Athenæum.

This is, however, further complicated by a couple of instance of Sir Humphrey meeting his great rival, Sir Frank Gordon of HM Treasury, for lunch at the Reform Club. But the clear inference on these occasions is that it is Sir Frank hosting both of these lunches at the Reform, where he is a member.

Anthony Sampson captured how in the 1960s and 1970s, the Reform Club hit the peak of its phase as a “Treasury works canteen”, rivalling the neighbouring Travellers Club (as the Foreign Office's club of choice). It would have been near-certain for Sir Frank to have been a Reform Club member by the 1980s. This teases out how sometimes a particular departmental affiliation could make a club membership more likely - but that the Athenæum nonetheless remained the default club for Permanent Secretaries where this did not apply.

The clubs onscreen

In the TV series, the exact identity of the clubs is left ambiguous. It should be pointed out that the explicit naming of the Athenæum and Reform didn't happen until the publication of volume 1 of the book version of Yes, Prime Minister in 1986 (and was repeated in volume 2, published in 1987). This was several years after the main broadcast run of Yes, Minister (1980-2).

It is also worth pointing out that although Yes, Minister is often thought of as a quintessentially 1980s comedy, with Margaret Thatcher having been an avowed fan, much of its material was based on the Wilson and Callaghan government in the late 1970s. (The writers’ once-secret government sources have long since been “outed” as former special advisers Bernard Donoughue and Marcia Falkender.) I mention this because the portrayal of clubs seems steeped in the 1970s, too.

The Yes, Minister pilot (‘Open Government’) shows us a club set that was never used again - though design elements were recycled later on. I call this “Club A.” Already, the relationship foundations were laid for club scenes throughout the series, with Sir Humphrey and Sir Arnold being fellow members, and Bernard Woolley being a somewhat frostily-received guest. The decor of this club is closer to Boodle’s or Brooks’s in the 1980s, than to the Athenæum or the Reform Club.

We see a particularly nice aside in the pilot episode, when Sir Humphrey wanders off to take a call from the club's phone booth, and this offers us some lovely period detail on the set, especially with the light fitting. We'd never see this area again. There is a telephone booth in the Athenæum’s main lobby, by the entrance, which is not dissimilar in design.

Series 2 & 3 (episodes ‘The Devil You Know’ & ‘The Challenge’) give us “Club B.” This is really a recycling of elements of the “Club A” set from the pilot (pillars, armchairs, etc), in a similar configuration, but with major changes, too - bookcases where there were paintings, etc. Gone is the gloomy lighting, replaced with something brighter, and walls painted in much paler colours. It gives us less atmosphere, but we can see the comedic performances more clearly.

It is quite possible - and indeed likely - that this is intended to be the same club as “Club A” from the pilot, after a major redecoration. Clubs redecorated and reinvented themselves far more often than they liked to admit, with plenty of “historic” décor being modern pastiches.

Series 2 & 3 (episodes ‘The Quality of Life’, ‘The Challenge’ & ‘The Middle-Class Rip-Off’) also show us this Club’s dining room set, which I call "Club B2". You might think it is an entirely different club, with its very-much-of-its-time 1970s floral wallpaper - but it’s explicitly stated to be part of the same club. In ‘The Quality of Life’, Sir Humphrey emerges straight from a lunch in “Club B2”, to walking through the “Club B” set, where he bumps into Sir Desmond Glazebrook, nestled beneath a newspaper in an armchair. It's clearly meant to be the same club - one set is the dining room, the other is the smoking room.

The windows seen in “Club B2” are interesting: they have wooden panelling on the recesses, reminiscent of several clubs (the Reform comes to mind). Yet the radiator is conspicuously out of place (though might be a reflection of the shabby state of clubs by the 1970s). Meanwhile the 1970s wallpaper is decidedly eye-catching - a point worth stressing, because…

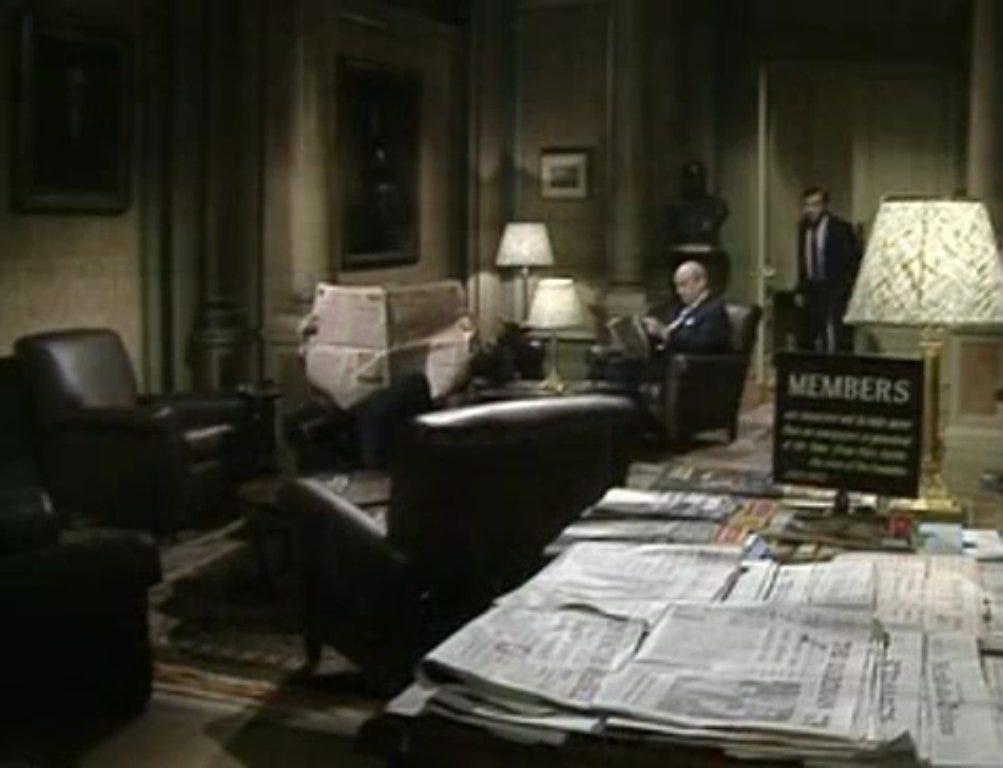

In the 1984 Yes, Minister Christmas special, ‘Party Games’ (where Hacker becomes Prime Minister), we get “Club B3” - it's an entirely new set, with a new dining room, and new wallpaper...but the ‘look’ (especially the wallpaper) is sufficiently evocative, that it was almost certainly meant to portray the same club.

Of course, the real-life explanation is almost certainly that when Yes, Minister finished its regular run in 1982, the clubroom set would have been demolished, and there would have been no idea that a one-off Christmas special would be commissioned another two years later, requiring a further glimpse into Clubland. And so this set was rustled up for the occasion, and used just once.

Talking of demolished sets, it is now worth going back to the generic club set used throughout series 1 of Yes, Minister ( in the episodes ‘The Official Visit’, ‘The Economy Drive’, ‘The Writing on the Wall’ & ‘The Right to Know’). They recycled the pillars from the pilot, but created a new set - which was presumably torn down after the first series, and was never used again.

This series 1 set - almost certainly intended to be located within the same club as Clubs A, B, B2 & B3 - was arguably more authentic than some of the others in Yes, Minister. A side-by-side comparison shows how it captures the feel of the Morning Room of the Athenæum, which houses its main bar.

Further clubs seen in Yes, Minister

In the opening episode of series 2, ‘The Compassionate Society’, we unambiguously see a different club, when Sir Humphrey meets Sir Ian Whitchurch, Permanent Secretary to the DHSS.

Unlike Clubs A/B/B2/B3, which use many 'typical' but non-specific club design elements, the set for Sir Ian’s club is very obviously modelled on the Smoking Room of the Reform Club, matching its lighting, pillars and furniture. It's a very detailed set - and we never see it again in the series.

Then in series 3's ‘The Bed of Nails’, we see Sir Humphrey briefing journalist Peter Maxwell and then “accidentally” leaving a confidential document on his table after a heavy lunch. The set, with its Vanity Fair prints on wooden pannelling, heavy purple curtains and potted palms, looks a lot like the old London Press Club on Wine Office Court, off Fleet Street, before it lost its premises in 1986.

Both of these clubs are examples of the series’ set designers doing thorough research, to maximise authenticity.

Bernard Woolley

Before moving onto Yes, Prime Minister, it is worth saying a few words about Bernard Woolley, the long-suffering Principal Private Secretary to Jim Hacker - with divided loyalties towards Sir Humphrey.

Bernard’s status in these clubs is very precarious - he is usually treated as a mere errand boy, delivering a message. He may be considered a “high-flyer” in the civil service, on the fast-track to senior promotion - but he's not (yet) a member of the Athenæum, unlike Sir Humphrey and Sir Frank. (I say “yet”, because the books spell out that after the series, the by-then-Sir Bernard went on to become Head of the Home Civil Service.)

When Bernard visits the clubs in Yes, Minister, his presence is more tolerated than invited: he is primarily there to collect signatures on urgent papers (something technically forbidden in many clubs at the time - though this may not always have been enforced). Very occasionally, he was invited to join Sir Humphrey and Sir Arnold for a drink, but always as an outsider, and in a strictly subordinate capacity. (“Get yourself a coffee,” Sir Humphrey says to him condesendingly, as he sips red wine.)

The club in Yes, Prime Minister

By the time the show returned for Yes, Prime Minister in 1986, it was one of the BBC's most popular programmes, and the budget had visibly increased. No more tatty club sets with 70s wallpaper. We see two club rooms throughout Yes, Prime Minister, each a variant on the other, recycling props between the two.

We see the first of these club rooms across both series of Yes, Prime Minister (episodes ‘The Smoke Screen’, ‘One of Us’, ‘Power to the People’, & ‘The National Education Service’). It is frequented by Sir Arnold, Sir Humphrey and Sir Frank - even though the books suggest the scenes are supposed to be set in both the Athenæum and the Reform Club. Clearly, having spent so much money on this sumptuous new set, the programme was determined to get the most use out of it.

And there is still no sign of poor Bernard frequenting this Club. He's now PPS to the Prime Minister, but he doesn't seem to have been elected a member - clearly the waiting list is a long one in the 1980s.

The second of these Yes, Prime Minister club rooms is a dining room that is clearly a redress of elements of the first set, with recycled pillars, chandeliers, plants, etc. Given the shared design elements with the first room, it's clearly intended to be part of the same club. It shows up in one episode of each series of Yes, Prime Minister (‘A Real Partnership’, and ‘Man Overboard’).

Is it intended to be the same club as the (admittedly tattier) Athenæum-type club set we've seen before, in Yes, Minister? There's one obvious architectural clue.

Above, I flagged up the white wooden panelling by the window recesses, flagged up in “Club B2” in Yes, Minister. That is echoed in the architecture of the Yes, Prime Minister club. (Then again, that is far from being conclusive proof that they are the same club.)

On the other hand, the staff uniforms with white dinner jackets in both rooms of the Yes, Prime Minister club (above left) are identical to the staff uniforms we previously saw in the club in the Yes, Minister episode ‘The Compassionate Society’, which was so closely based on the Reform Club (above right). So the television series clearly obfuscates this. We have to just accept that the television version of Yes, Prime Minister has a sort of ephereal Clubland where the characters could almost be in any club.

Conclusion

The books couldn't be clearer, that the Athenæum is the club of both Sir Arnold Robinson, and his successor as Head of the Home Civil Service, Sir Humphrey Appleby; while the Reform Club is frequented by Sir Frank Gordon, Permanent Secretary to HM Treasury. And Sir Humphrey is already a member of the Athenæum when he is Permanent Secretary to the Department of Administrative Affairs.

Yet the TV version obfuscates this point considerably. Clubs A, B, B2 & B3 & the “series 1 club” seen in Yes, Minister are probably all the same club, with multiple rooms shown across different redecorations, and is probably also meant to portray the Athenæum.

But the club seen throughout the screen version of Yes, Prime Minister...is a lot more ambiguous. They spent a lot more money on the Yes, Prime Minister club set, and it did not particularly resemble what had been seen onscreen before - it was taller, lighter, airer & more sumptuous. There was a sense in Yes, Prime Minister that every ‘generic club scene’ was filmed using those elements, regardless of the location it was meant to be in.

And in Yes, Minister, we saw the Reform Club and London Press Club, and those were established to not be the haunts of Sir Arnold and Sir Humphrey. There was also some ambiguity as to whether some other scenes throughout the series were set in clubs, high-end restaurants, or offices. (For instance, one scene with a club-like ambiene nevertheless had a work desk in the background, suggesting an office.)

Further reading

Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn, Yes, Prime Minister: The Diaries of the Right Hon. James Hacker, Volume I (London: BBC Books, 1986).

___________________, Yes, Prime Minister: The Diaries of the Right Hon. James Hacker, Volume II (London: BBC Books, 1987).

(This piece was adapted from an old Twitter thread I wrote on the topic two years ago.)

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

Has anyone a copy of the BBC series A Gentleman's Club, which ran in the late eighties? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Gentleman%27s_Club

That's a really innteresting & informative post, Seth. I've often wondered about the clubs depicted in the TV series and which ones they were supposed to be (isn't there also an actual Civil Service Club, too?). Funnily enough, I'll be referencing a quote from 'Yes Prime Minister' in one of my upcoming sermon-intros!