Lost Clubs: The Constitutional Club (1883-1979)

The first attempt at a mass-membership club for Conservatives

The Constitutional Club provided a barometer for the changing trends in the political clubs of London: founded amid the confidence of the late Victorian era, with an opulent clubhouse, but battered by events and poor management through much of the 20th century, and shifting around between multiple addresses until it went under in the 1970s.

The clubhouse pictured in 1961, prior to its demolition the following year. (Photo credit: Charles W. Kuchman collection - University Archives, University of Bloomington, Indiana.)

Origins

The first two Reform Acts - 1832 and 1867 - each expanded the British electorate. After each one, the main parties had set up politically-themed clubs as a way of connecting with these new voters, and organising efforts to woo them and retain them. Examples include the Carlton Club for Conservatives in 1832, the Reform Club for Liberals in 1836, the St. Stephen’s Club for Conservatives in 1870, and the Devonshire Club for Liberals in 1874.

The Third Reform Act of 1884-5 was slightly different. Further extensions to the franchise had been debated for years, and both parties could see it coming. So in anticipation of it, the parties set up new clubs beforehand: the Liberals with the National Liberal Club in 1882, and the Conservatives with the Constitutional Club in 1883. It was briefly known as the Caucus Club for its first few months in 1883, with the intention to unite the Conservative caucus of voters, before settling on a name aimed at stressing constitutional principles.

These new clubs were conceived of as mass-membership clubs. While the traditional aristocratic Georgian clubs had only a few hundred members each, and post-Reform Act clubs like the Carlton Club and the Reform Club had a little over 1,000 members each, these new clubs were designed to accommodate over 6,000 members. The target audience was made up of new, lower-middle-class provincial voters with a strong party affiliation, who did not already have a London club. The intention was to make club facilities available, on a larger scale, to people who had not already been embraced by London Clubland (though many were already members of the provincial political clubs set up in big cities like Leeds and Manchester from the 1860s). Subscriptions and joining fees were to be set at around half of those found at the more established London clubs.

The Club would later recount that the initial inspiration for the Constitutional Club came not from its fellow London clubs, but from the mass-membership Conservative Club in Glasgow. The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, the Conservative leader, asked why there was no equivalent in London, and the 1st Marquess of Abergavenny set about overseeing the project. Salisbury promptly accepted the presidency of the new club.

The changing locations of the Constitutional Club’s clubhouses. (Base map: Google maps.)

The Regent Street years

The Club’s first home, on a temporary basis from August 1883 to October 1886, was at 14 Regent Street. It was next door to the Raleigh Club, a social club at number 16. The Constitutional Club’s Regent Street residence was a John Nash-built house (now demolished), occupied while a palatial, purpose-built new clubhouse was constructed on Northumberland Avenue.

The Regent Street clubhouse was in many ways a recycling of its previous use. In 1864, the Junior Carlton Club had been created as a larger overflow for the Carlton Club; and for the five years that it took to construct its Pall Mall clubhouse, the Junior Carlton Club had been based at 14 Regent Street from 1864-9. It was therefore exceptionally appropriate for an interim home - if at times overcrowded.

The Northumberland Avenue clubhouse from 1886-1962. (Picture credit: Illustrated London News, 29 August 1885, p. 208.)

Northumberland Avenue

Northumberland Avenue, running from Trafalgar Square to the newly-developed Thames Embankment, was a new street at the time. It was created on the site of the early 17th century Jacobean mansion Northumberland House, belonging to the Percy family, which had been demolished in 1874. The new area, with its central location, became home to London’s hotel district, with tall new ten-storey structures arising in the 1880s. The plot of land selected for the Constitutional Club had briefly been earmarked for a Wyndham’s theatre, but the development lay unfinished. The freehold was purchased by the Club for £80,840 (around £13.3 million today).

Map of the principal floors of the clubhouse, as rendered by R. W. Edis. (Picture credit: author’s collection.)

Robert William Edis was selected as architect, and set about building a distinctive building. Like its nearby rival the National Liberal Club, it occupied an asymmetrical triangular plot of land, and used elaborate geometrical patterns in its room layouts to conceal the unusual shape of the building; it also had a circular turret tower. The building was an early pioneer of electrical lighting throughout, with 750 light bulbs, fed by an engine and dynamo in the basement.

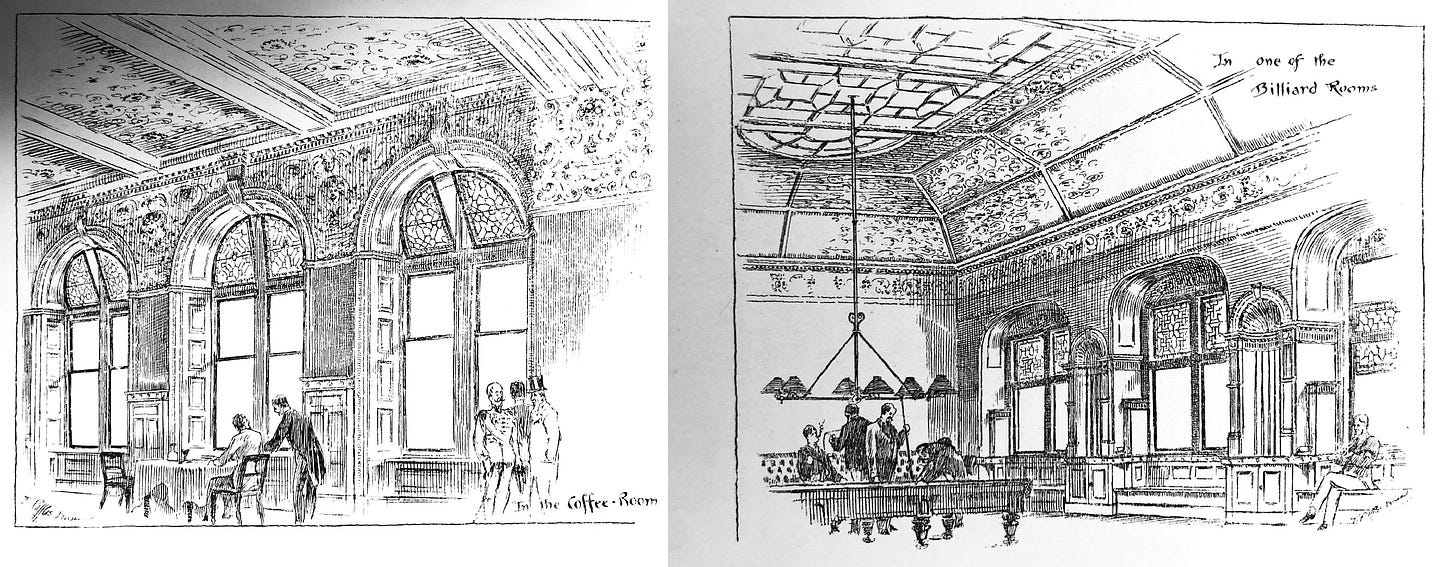

Scenes from the Northumberland Avenue clubhouse. (Picture credit: Sketches from Anonymous, The Constitutional Club, R. W. Edis, F.S.A., Architect - Founded 1883 (London: The British Architect, 1890).)

Also like the National Liberal Club, the building made extensive use of decorative faience tiling to stress its connection to Britain’s manufacturing classes; though the decor tended to favour more earthy terracota than the NLC’s Burmantofts Pottery ceramics.

More scenes from the Northumberland Avenue clubhouse. (Picture credit: Sketches from Anonymous, The Constitutional Club, R. W. Edis, F.S.A., Architect - Founded 1883 (London: The British Architect, 1890).)

On a practical level, the Club supplemented the ‘core’ club offering around dining room, billiars room, card room, smoking room and refreshment room with 84 bedrooms, and a well-stocked, well-funded library.

More scenes from the Northumberland Avenue clubhouse. (Picture credit: Sketches from Anonymous, The Constitutional Club, R. W. Edis, F.S.A., Architect - Founded 1883 (London: The British Architect, 1890).)

Political activity

The Club retained its political link through an active Political Committee, paralleling the structure of the Carlton, Junior Carlton and St. Stephen’s Clubs in this respect, fundraising for Tory election campaigns.

This focus on campaigns included a political fund, a “political register” recording the distribution of members based in each parliamentary constituency , a lecturing van (a cart) touring the constituencies, a volunteer speaker corps programme, and a programme for hosting constituency association events at the Club. The NLC did the same for the Liberals, making these very much equivalent organisations to one another.

Figures from 1890 suggest the political fund does not seem to have been particularly significant - as was often the case with club political funds in the 19th century. It was run on an opt-in basis, with most contributions paying a suggested 10 shillings. But only 132 of the 6,000 members contributed to it (just 2.2% of members); and the sum total raised of £64, 11 shillings (about £11,000 today) was not particularly impressive, particularly when spread between multiple constituencies.

The Club also ran an internal programme for members, including hosting political discussions at club events, and arranging house dinners. Tariff reform was highly popular with members in the Edwardian era, with members strongly favouring Joseph Chamberlain’s campaign for imposing imperial-preference tariffs on British goods.

Like the other Conservative clubs of the day, Conservative MPs, peers and the eldest sons of peers were all able to bypass the waiting list, and go straight to a ballot for election upon application. Consequently, parliamentarians were well-represented among the membership: for instance, the general election of 1918 saw 69 members elected as MPs.

Members

Membership was heavily political: as at the Carlton and Junior Carlton, members were required to swear allegiance to the Conservative cause; although this did not stop the politically apathetic from cheerfully perjuring themselves to access the Club’s facilities. A 1911 amendment to the rules allowed ‘Unionists’ to join, mainly intended to pave the way for Liberal Unionists as they merged with the Conservatives.

Arguably the Club’s best-known member was avowedly non-political: P. G. Wodehouse. Wodehouse often cited the Constitutional Club as his favourite of his half-dozen London clubs, and a thinly-veiled version of it recurred in several of his books, as “the Senior Conservative Club” on Northumberland Avenue, next door to the Turkish baths (which were a real-life fixture neighbouring the Constitutional Club).

While the Club’s membership was heavily provincial (as one might expect from its founding ideas), a substantial minority of members were in fact Town members based in London. Figures from 1890 show 4,078 country members to 1,989 town members. These 1,989 town members broke down further to include 700 living in the West End, 400 in the City, and 300 around the Strand.

In the 1900s, in a bid to prevent overcrowding of the clubhouse, town membership was capped at 2,300, and country membership was capped at 4,200.

The Committee Room of the Northumberland Avenue clubhouse. (Photo credit: Philip G. Cambray, Club Days and Ways: The Story of the Constitutional Club, London, 1883-1962 (London: Constitutional Club, 1963), colourised with the Kolorize.CC app.)

Difficulties

The Constitutional Club faced predictable difficulties in both World Wars: rationing and staff shortages were prevalent in most clubs. In September 1916, the building was seized by the Ministry of Munitions for war work. (In a display of partisan even-handedness, the National Liberal Club was seized at the same time.) The building was not returned to members until April 1919.

In the Second World War, conscription and the Blitz meant that members increasingly stayed away from the building, triggering an internal inquiry into the financial position of the Club. A further inquiry was to follow a decade later, with the Club’s finances only worsening.

Edis’s building had been the height of fashion in the Victorian and Edwardian era, but fell out of favour by the post-war years. At a series of Special General Meetings between 1958-9, the Club’s management proposed a new scheme which was to be a popular business model for clubs in the 1960s: demolition of the Victorian clubhouse, construction of an office block on the site, with the Club intended to occupy a penthouse atop the new building and enjoying rental income from the building below. In the face of stiff opposition, the proposal passed in 1959, and on 27th August 1962, the Club vacated the premises.

Despite the original plan, the Club would never return to Northumberland Avenue: the Club spent the rest of the decade moving between temporary premises, and the freehold on Northumberland Avenue was ultimately sold on in 1969, as the Club instead chose to acquire a more traditional clubhouse in St. James’s.

The 1960s

On the demolition of the Northumberland Avenue building, the Constitutional Club once agains found its fate intertwined with that of the Junior Carlton Club, by now long established at 30 Pall Mall.

From 1962 to 1964, the Constitutional Club was hosted by the Junior Carlton Club. Even within the two-year period, this was not as stable as it may sound, for in August 1963, the Junior Carlton began the process of demolishing its own building and replacing it with the present office block, duplicating the very plan of the Constitutional Club with the Pall Mall clubhouse. For this reason, the Constiutional was hosted from 1963-4 by the Carlton Club at 69 St. James’s Street, when the Junior Carlton moved in with them.

Finding being a sub-club of a sub-club less than congenial, the arrangement ended in 1964, when the Constitutional Club moved in with the United Service Club at 116 Pall Mall, where it joined a rag-bag of other clubs hosted by the military club. This arrangement lasted until 1969. (They also had the recently-displaced Savage Club lodging with them from 1968 until 1975, further complicating this arrangement.)

St. James’s Street

By 1969, the Constitutional Club had sold the freehold on Northumberland Avenue, and used the money to acquire its own address at 86 St. James’s Street - which was to prove to be its last standalone home. The building had a varied history, and was where several clubs had gone to die: the Thatched House Club ended up there before its closure in 1949, and the Union Club (best known for its old home on Trafalgar Square) had its final clubhouse there before folding in 1964.

The Club spent much of the 1970s financially ailing, and in 1977 a decision was made to put the St. James’s Street clubhouse on the market. The building was sold to the Freemasons, for use as Mark Masons’ Hall, the headquarters of the Grand Lodge of Mark Master Masons of England and Wales, which it remains to this day. The Constitutional Club continued to occupy the building until 1979, while major alterations were undertaken, and the Constitutional negotiated a merger into the Conservative-affiliated St. Stephen’s Club at 34 Queen Anne’s Gate.

Closure and aftermath

1979 saw the Club cease to be an independent entity. It was amalgamated into what was for a while formally known as the St. Stephen’s and Constitutional Club. Yet by the mid-1980s, this unwieldy mouthful reverted to being known as the St. Stephen’s Club, and the Constitutional Club influence faded into simply having been a source of members. The Club limped on through successive financial difficulties and multiple bail-outs and owners, before closing down in January 2012.

Meanwhile, the Constitutional Club’s old Northumberland Avenue site has since been redeveloped twice over, and is now the Korean Cultural Centre, opposite the Sherlock Holmes pub.

Further reading

Anonymous, The Constitutional Club, R. W. Edis, F.S.A., Architect - Founded 1883 (London: The British Architect, 1890).

Philip G. Cambray, Club Days and Ways: The Story of the Constitutional Club, London, 1883-1962 (London: Constitutional Club, 1963).

The seal of the Constitutional Club.

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.