George MacDonald Fraser’s best-selling Flashman novels - known as ‘The Flashman Papers’ (1969-2005) - followed the misadventures of its anti-hero across various 19th century wars. Unsurprisingly, the fictional Brigadier-General Sir Harry Flashman (1822-1915) found himself in quite a few private members’ clubs.

Harry Flashman

Flashman started life in Thomas Hughes’ 1857 novel Tom Brown’s School Days - he was “the School-house bully”, a “brute” who was expelled from Rugby for drunkenness, half-way through the book. Over a century later, the Scottish novelist George MacDonald Fraser hit upon the conceit of tracing this fictional character’s life story after Tom Brown’s School Days. And so a minor character - whom Hughes did not even give a first name - was developed by Fraser into Brigadier-General Sir Harry Paget Flashman V.C., K.C.B., K.C.I.E., leading a Zelig-like existence, present at almost every great military disaster of the 19th century, from Peking to Pennsylvania.

By his own admission, Flashman is “a scoundrel, a liar, a cheat, a thief, a coward and and a toady” - a loathesome anti-hero who does despicable things in each book. Yet through a combination of his own lying, and an improbable set of coincidences, he is invariably showered with praise as a hero. The books are written in a confessional tone, narrated by a retired Flashman who is disarmingly honest about his many failings, while Fraser uses this device to offer up extensive satirical observations on Flashman’s contemporaries and their times. Fraser extensively researched the books, so that they were plausibly set around real-life historical events, and depicted fictionalised versions of real-life individuals. And as they revolved around British imperial history, they naturally involved clubs.

Flashman, as pictured on the cover of the 1999 edition of the first book (1969).

Flashman’s father, and his club

The first reference to a specific club comes early in Flashman (1969), shortly after the title character’s expulsion from Rugby in 1839, when his father’s reaction to hearing that he was thinking of joining the army, was:

“You mean I’m to buy you colours so that you can live like a king and ruin me with bills at the Guards’ Club, I suppose?”

(Flashman replies that he had the dragoons in mind; and there is no further suggestion of his ever joining the Guards Club - though in Flashman in the Great Game (1975), set 17 years later, he emerges from the Guards Club alongside another officer, Spottswood, who is presumably his host.)

His father, Captain Henry Buckley Flashman, was described as “a dissolute former MP, living beyond the bounds of respectable society.” He is an alcoholic who ends up being institutionalised by his own son. Flashman Senior was himself a club member - we know this, because while he is away in Flashman (1969) “at the club that night”, Harry Flashman takes the opportunity to seduce his father’s mistress. Although the Club is unnamed, my guess as to its identity would be White’s.

The greatest clue to it being White’s is that Harry Flashman himself later belonged to White’s, at a time when its biggest determinent of membership was overwhelmingly down to family connections. My own analysis of the post-1832 composition of White’s was that its political ties weakened, because family played a much bigger role than politics, with membership passing from father to son - even when families shifted from Tory to Whig over the generations. (Even when convention forbade fathers from nominating their sons, it was common practice at White’s for two friends to skirt around this by “swapping” nominations for one another’s sons.)

Despite the weakening political link at the time, White’s membership would have also been consistent with Henry Buckley Flashman’s conservative politics (his political career as an MP “ended at Reform”). There would also be a logical symmetry to Flashman Sr. looking down upon the Guards Club, since at that time, it was located directly opposite White’s, on the west corner of St. James’s Street and Piccadilly, next door to Crockford’s.

On the other hand, the fuller account of Captain Henry Buckley Flashman in Black Ajax (1997) suggests it could have been just about any London club that harboured gambling. Flashman Senior recalled that when he returned to London in 1809, he:

“Lost a careful amount at Crocky’s hell in Oxford Street, but was nowhere near Brooks’s or Waitier’s where the real gamsters played.”

We can therefore rule out the latter two gambling clubs of Brooks’s and Waitier’s. His reference to “Crocky’s” is to the pop-up gaming houses run by William Crockford before his more salubrious St. James’s Street club opened in 1823. We can also rule out his membership of this later Crockford’s club, as its existence did not overlap with the timeframe of the story - Tom Molyneux, the “Black Ajax” of the title, died in 1818, five years before Crockford’s opened.

Flashman Sr. says he later:

“Came to mingle with the upper crust, was welcomed from Almack’s [salon] and Boodle’s to Bob’s Chophouse and Fishmonger’s Hall [Crockford’s].”

Given that of these, only Boodle’s was a club at the time, this can simply be taken to mean that he gambled within that wider realm - though it might also suggest Boodle’s as a possible candidate for his club. (Perhaps they refused to elect his son, precisely because Flashman Sr. had been a member?)

And none of this precludes Flashman Sr. having frequented multiples clubs. Whilst Henry Buckley Flashman belonged to “the club”, suggesting just one membership, his son notes:

“He never saw much of me, being too busy at the clubs or in the House or hunting.”

Harry Flashman’s early experience of the Minor Club

The first time we see Harry Flashman in a club, it is as a visitor. In Royal Flash (1970), the second book in the series, he recalled that as a 20-year-old Captain in 1842:

“I was in with the fast set, idling, gaming, drinking and raking about the town”

and that he had been drawn to visit the Minor Club in St. James’s - a short-lived, real-life club, combining a gambling room downstairs and a brothel upstairs - about which Fraser’s footnote cites L. J. Ludovici’s The Itch for Play:

“Its proprietor, a Mr Bond, was successfully sued that year by a disgruntled punter who received £3,500 in respect of his losses.”

Royal Flash’s account presents Flashman’s first visit to the Minor Club as having been a close-run thing, only narrowly escaping when the club was raided by police - something which a footnote recognises was increasingly common in gambling clubs after the 1839 Metropolitan Police Act.

And Flashman was moderately paranoid about the conduct of gambling in clubs. Noting the various crooked games in which he had participated around the world, he believed:

“I’ve met less sharping in all of ‘em put together than you’d find in one evening in a London club.”

In support of this, Fraser tells us in a footnote that

“the 2nd Marquis of Conyngham was among the victims fleeced at Mr Bond’s Minor Club; he lost at least £500 on two occasions in 1842.”

This may also explain Flashman’s gung-ho enthusiasm for cheating at cards - the assumption that everyone else will be cheating anyway, and that he needs to win through cheating before someone else does.

Harry Flashman’s club memberships

Harry Flashman’s London clubs are given in his biographical note as White’s and the United Service Club. He is explicitly stated to have resigned from both, for reasons that are never specified in the books. He has also been a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club (M.C.C.) (technically outside of London at the time), apparently in good standing.

A fuller version of the character’s engagement in associational culture is given in the biographical note at the start of Flashman on the March (2005):

“Hon. mbr of numerous societies and clubs, including Sons of the Volsungs (Strackenz), Mimbreno Apache Copper Mines band (New Mexico), Khokand Horde (Central Asia), Kit Carson’s Boys (Colorado), Brown’s Lambs (Maryland), M.C.C., White’s and United Service (London, both resigned), Blackjack (Batavia).”

Flashman and White’s

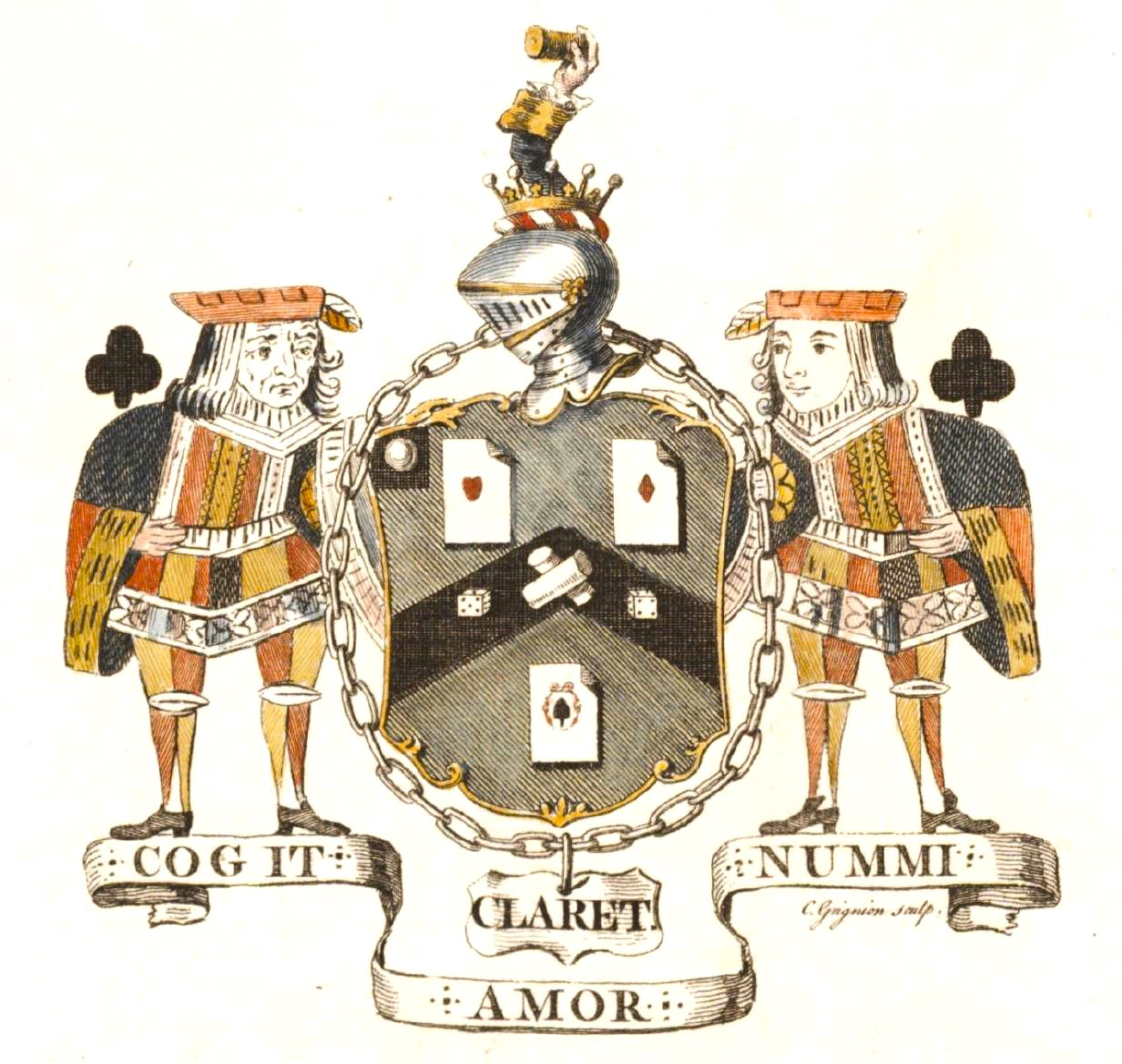

White’s, with its gaming culture (immortalised in a coat of arms showing cards and die on a baize background), and its motto of Cogit amor nummi (“The love of money compels him”) would have appealed to Flashman. Given the close-run nature of the 1842 incident at the Minor Club, White’s would have also offered far greater impunity against the risk of police raids.

The White’s coat of arms, originally devised as a piece of burlesque heraldry by members Richard Edgecumbe, George Selwyn Horace Walpole, and George J. Williams in 1756, and later put on permanent display in the front lobby, pays tribute to the Club’s gaming culture.

It is not clear when Flashman was elected to White’s - certainly after the 1842 events at the Minor Club, when he was clearly an outsider to this world - but given how much time he spent abroad, it is quite likely that he was not elected until several years later, upon returning to London to take up his place. White’s had a small membership of around 300 or so at the time, and the waiting list was relatively short - the main challenge to joining was securing enough support, not waiting for places to come up. If Flashman’s father had acted as proposer, then he was likely to have proposed his son at some point in the 1840s, prior to his having been institutionalised.

Interestingly, the real-life historical membership list of White’s does not list anyone named Flashman elected to the Club (perhaps their names were expunged from the records for gross misconduct…), yet there were no fewer than 19 members of the Paget family elected as members of White’s between 1788 and 1889, with 11 of them elected before 1848. Harry Paget Flashman’s mother, the Hon. Alicia Paget, was a scion of the Marquesses of Anglesey, and so it might be inferred that Flashman’s maternal aristocratic connections helped him (and his father before him) to secure election to White’s.

Indeed, if we take this conceit further, with Flashman having lived until 1915, we might deduce that whatever Flashman did to merit expulsion from White’s proved so mortifying that not only was his name removed from the books along with that of his father, but that it ensured that no relative of his was elected after 1889. It must have also happened before 1892, as the surviving historic membership list which conspicuously omits his name went to print then, for the Club’s 200th anniversary history. We can therefore deduce that it happened sometime between 1889 and 1892.

As it happens, the events of ‘The Subtleties of Baccarat’ in Flashman and the Tiger (1999) detail Flashman’s role in the Tranby Croft card scandal of 1890-1, which rocked English society, dragging the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) into open court as a witness. And the Prince was indeed a member of White’s. The timeline of this tallies perfectly with the above events, in suggesting a compelling reason for why and when Flashman would have been recently expelled by 1892 - especially as the Club was keen to maintain its favour with the Prince.

Flashman and the United Service Club

We know relatively little about Flashman’s membership of the United Service Club, but its pre-1892 practice of only electing army officers of the rank of Major and above means that we can infer he could not have been elected until at least 1855. (During the 1854-5 events of Flashman at the Charge (1973), he is promoted from Captain to Colonel.)

However, he did not return to Britain until the first half of 1856, at the start of Flashman in the Great Game (1975). He recalled settling into a new routine:

“There I was in the summer of ‘56, safely content on half-pay as a staff colonel, with not so much as a sniff of war in sight…I was comfortably settled…in a fine house off Berkeley Square…dropping by occasionally at Horse Guards, leading the social life, clubbing and turfing”

The summer of 1856 therefore seems a prime candidate for when Colonel Flashman, “the hero of Kabul and Balaclava”, would have been promptly elected to the United Service Club after his promotion.

Flashman and the M.C.C.

We learn more about Flashman’s aptitude for cricket in Flashman’s Lady (1977), which gives some background to his joining the Marylebone Cricket Club, then already based at Lord’s Cricket Ground in St. John’s Wood, outside the contemporary boundaries of London.

Flashman admits to some pride over his talent for cricket:

“When I look back nowadays on the rewards and trophies of an eventful life - the medals, the knighthood, the accumulated cash, the military glory, the drowsy, satisfied women - all in all, there’s not much I’m prouder of than those five wickets for 12 runs against the flower of England’s batters, or that one glorious over at Lord’s in ‘42”

He makes it clear that he began playing cricket with some skill during his school days in the 1830s, as part of Rugby’s team, working towards a match at Lord’s:

“It was in the ‘thirties, you see, that round-arm bowling came into its own, and fellows like [Alfred] Mynn got their hands up shoulder-high. It changed the game like nothing since, for we saw what fast bowling could be - and it was fast - you talk about Spofforth and Brown, but none of them kicked up the dust like those early trimmers. Why, I’ve seen Mynn bowl to five slips and three long-stops, and his deliveries going over ‘em all, first bounce right down to Lord’s gate. That’s my ticket, thinks I, and I took up the new slinging style, at first because it was capital fun to buzz the ball round the ears of rabbits and funks who couldn’t hit back, but I soon found this didn’t answer well against serious batters who pulled and drove me all over the place. So I mended my ways until I could whip my fastest ball onto a crown piece, four times out of five, and as I grew tall I became faster still, and was in a fair way to being Cock of Big Side - until that memorable afternoon when the puritan prig [Tom] Arnold took exception to my being carried home sodden drunk, and turfed me out of the school. Two weeks before the Marylebone match, if you please - well, they lost it without me, which shows that while piety and sobriety may ensure ensure you eternal life, they ain’t enough to beat the MCC.”

Flashman’s penchant for cricket is explored in Flashman’s Lady (1977).

After Flashman’s expulsion from Rugby, he concedes:

“that was an end to my cricket for a few summers, for I was packed off to the Army and Afghanistan”

which accounts for the events of the first Flashman book, spanning 1839-42. The beginning of Flashman’s Lady (1975) picks up the story when

“I came home a popular hero in the late summer of ‘42, to a rapturous reception from the public”

Bumping into his old school nemesis Tom Brown in The Green Man pub (“a famous haunt of cricketers”), he accepts Brown’s invitation to join the Rugby old boys’ team for a match against Kent, held at Lord’s cricket ground. Recalling the match of 1842, the elderly Brigadier-General Flashman reminisced:

“It looked so different, even; if I close my eyes I can see Lord’s as it was then…The coaches and carriages packed in the road outside the gate, the fashionable crowd streaming in by Jimmy Dark’s house under the trees, the girls like so many gaudy butterflies in their summer dresses and hats, shaded by parasols, and the men guiding ‘em to chairs, some in tall hats and coats, others in striped weskits and caps, the gentry comfortably buttoned up and the roughs and townies in shirt-sleeves and billycocks with their watch-chains and cutties; the bookies with their stands outside the pavilion, calling the odds, the flash chaps in their mighty whiskers and ornamented vests, the touts and runners and swell mobsmen slipping through the press like ferrets, the pot-boys from the Lord’s pub thrusting along with trays loaded with beer and lemonade, crying ‘Way, order, gents! Way, order!’…

“Or I see it in the late evening sun, the players in their white top-hats trooping in from the field, with the ripple of applause running round the ropes, and the urchins streaming across to worship, while the old buffers outside the pavilion clap and cry ‘Played, well played!’ and raise their tankards, and the Captain tosses the ball to some round-eyed small boy who’ll guard it as a relic for life, and the scorer climbs stiffly down from his eyrie and the shadows lengthen across the idyllic scene, the very picture of merry, sporting old England, with the umpires bundling up the stumps, the birds calling in the tall trees, the gentle evenfall stealing over the ground and the pavilion, and the empty benches, and with willow wood-pile behind the sheep pen where Flashy is plunging away on top of the landlord’s daughter in the long grass. Aye, cricket was cricket then.”

It is clear from the account in Flashman’s Lady that he is not yet a member of the M.C.C. in 1842; but that his status as a keen amateur cricketer, deeply rooted in th game, makes him an exceptionally strong candidate for membership at some point after this.

Colonial clubs

Flashman was an unusually well-travelled individual, particularly by the standards of his time: the stories refer to his visiting Abyssinia, Afghanistan, Australia, Austria-Hungary, Borneo, Bukhara, Canada, China, Dahomey, Denmark, Egypt, France, the German Confederation, the Gold Coast, Hong Kong, India, Madagascar, the Malay Peninsula, Mexico, New Guinea, the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, the Solomon Islands, South Africa, Sudan, Turkey and the USA - often spending months or even years at a time in these countries.

Yet we see Flashman visiting noticeably few clubs in these places - something all the more surprising when one considers how many of them were British colonies where the social life for the small British population revolved around the clubs; or how many clubs were found in the USA, where Flashman spent several years of his life (including much of the Civil War).

I suspect the reason for this is narrative. Unless a novel was a direct continuation of the preceding story, Flashman often started one of the books back home in England, on one of his rare visits home, before being catapulted to another adventure steeped in historical events worldwise. The scenes set in England were most likely to be at Flashman’s stately home at Gandamack Lodge, Ashby, Leicestershire - but when he was in London, the clubs provided the reader with an anchor to a familiar institution. Once Flashman was transposed to Asia or America, Fraser’s literary emphasis was on setting local atmosphere, and embedding Flashman into as much of the scenery as possible, rather than reminding readers of home.

On the balance of probabilities, it is highly likely that he visited a number of the clubs in these places - particularly the British military clubs in British colonies - but that these details were surplus to the requirements of the books, along with many of his long ocean voyages. He would not have been a member, but a guest. He would therefore most likely be familiar with the clubs of Bombay, Cairo, Calcutta, Cape Town, Durban, Hong Kong, Johannesburg, Macao, Madras, Manila, Melbourne, Ootacamund, Paris, Port Elizabeth, Singapore and Sydney.

I am less sure about his visiting American clubs - his status in US society was much more precarious during his time there, including stints as a fugitive from justice (and indeed he managed to fight on both sides in the American Civil War).

The only overseas club membership we know about, from his biographical note, was the Blackjack Club of Batavia [now Jakarta], the capital of the Dutch East Indies. He is listed as having been a member there, without having been expelled. He was presumably included on the ‘Overseas List’ when he returned home (i.e. he no longer paid a subscription once he moved abroad), and it is quite possible that the Tranby Croft affair was not as extensively reported in Batavia as in Britain.

Flashman’s Reform Club encounter with Gladstone

Flashman’s last major brush with Clubland comes in ‘Flashman and the Tiger’ (first published as a short story in 1975, and later included in the 1999 short story collection of that name). Set in 1894, it is chronologically the last of the Flashman stories (though an 88-year-old Brigadier-General Flashman does make a cameo in Fraser’s Mr. American (1980), in a scene set in 1914).

‘Flashman and the Tiger’ describes the 62-year-old Flashman’s encounter with Gladstone in the lavatories of the Reform Club, shortly after the latter’s resignation as Prime Minister on 4 March 1894:

“I passed the next few weeks agreeably enough. There was plenty of interest about town, what with a Society murder…and a crisis in the government, when that dodderer Gladstone finally resigned. I ran into him at the Reform Club - not a place I belong to, you understand, but I’d been to a champagne and lobster supper in St. James’s, and just looked in to unload. Gladstone was standing brooding over a basin in a nonconformist way, offensively sober as usual, when I staggered along, middling tight.

“ ‘Hollo, old ‘un,’ says I. ‘Marching orders at last, eh? Ne’er mind, it happens to all of us. This damned Irish business, I suppose -’ for as you know, he was always fussing over Ireland; no one knew what to do about it, and while the Paddies seemed to be in favour of leaving the place and going to America, Gladstone was trying to make ‘em keep it; something like that.

“ ‘Where you went wrong,’ I told him, ‘was in not giving the place back to the Pope long ago, and apologising for the condition it’s in. Fact.’

“He stood glaring at me, with a face like a door-knocker.

“ ‘Good-night, General Flashman,’ he snapped, and I just sank my head on the basin and cried: ‘Oh, God, what a loss Palmerston was!’ while he stumped off, and took to his bed in Brighton.”

Like Flashman, Gladstone in 1894 would have been a visitor at the Reform Club. He had previously joined the Reform Club, but relatively late in life, in 1869, when it was more-or-less expected of him as the recently-appointed Liberal Prime Minister, and he was the first member to be elected under new powers for the General Committee to elect no more than two people a year who were distinguished in public life. There is little evidence of his having used the club very much, and his membership lapsed in 1874, at the end of his first government. While Gladstone was a member of many clubs over the course of his life, he appears to have only made particularly heavy use of two, both on Pall Mall: the Carlton Club (during his earlier years as a Tory and then a Peelite), and the United University Club (for which he purchased pews for the servants, so they could worship nearby). We can therefore infer that if he was in the Reform Club in 1894, it was most likely as a guest speaker. (This seems a more likely explanation than his being there for a private meeting in the evening - with failing eyesight by 1894, it would have been more convenient for him to have summoned others to his home, whereas he is more likely to have ventured out if he wanted to address an audience; and the Reform Club in 1894 would have afforded him an audience among fellow Liberals.)

Conclusion

George MacDonald Fraser’s research for ‘The Flashman Papers’ was extensive, and this is reflected in the highly plausible way that clubs were portrayed, with the details all tallying. Little wonder that when the first Flashman book was published in 1969, the New York Times found that 10 of the first 34 reviews mistakenly believed that it was a real memoir.

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

Love those books. Imagine if they were made into films….