Lost Clubs: The United Service Club (1815-1975)

"The Senior": one of London's most influential clubs

116 Pall Mall, John Nash’s clubhouse occupied by the United Service Club from 1828 until 1975; embedding Decimus Burton’s 1850s architectural embellishments. On the left is the 117 Pall Mall annexe acquired by the Club in the 1850s, and embedded into the pre-existing building by Burton. (Photo credit: 116 Pall Mall website.)

The United Service Club was widely known as “The Senior” - partly to differentiate it from the Junior United Service Club, and partly because of its roots as a club for senior officers. In its 160-year history, it occupied one of the most conspicuous sites on Pall Mall, and it was highly influential in moulding the militarised shape of Victorian Clubland.

Origins

The Club’s origins were somewhat informal. It began with a group of senior army officers chaired by Lieutenant-General Thomas Graham, recently ennobled as the 1st Baron Lynedoch. They would meet in the Thatched House Tavern at 74 St. James’s Street; and on the 31st May 1815, they formed a General Military Club. After the Battle of Waterloo less than three weeks later, the Club assumed something of the character of a wartime reunion society, and it was decided to absorb the new Naval Club which had also been formed in 1815, so that in 1816, they merged under the name of the United Service Club.

Early buildings

From 1816, the newly-merged club occupied a residential townhouse in Mayfair, at 23 Albemarle Street. However, it was only intended as a stopgap while they raised funds for a palatial new clubhouse on Charles Street, which was completed three years later.

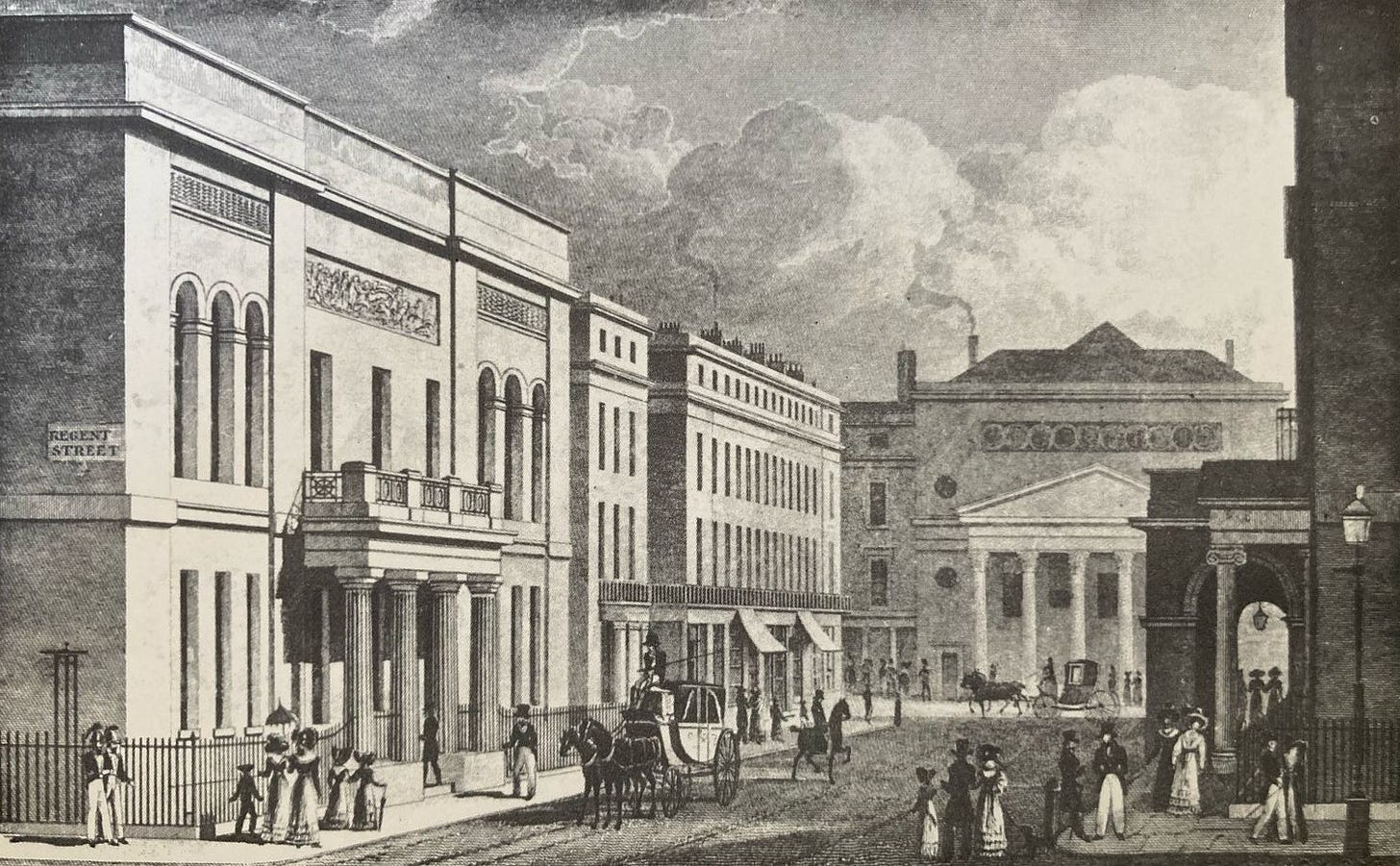

The Charles Street clubhouse (left) occupied by the United Service Club from 1819 to 1828, on the corner with Regent Street. It was later demolished in 1854. The Theatre Royal Haymarket can be seen in the distance.

In 1819, the Club moved to 11-12 Charles Street. The building was imposing, but suffered from a poor use of space, and proved to be impractical. Moreover, the building would have been one of the largest clubhouses in London when it was commissioned in 1816; but this was no longer the case barely a decade later. The surrounding district was in the middle of a period of great change, as Regent Street was constructed from 1810-25. The Club was soon dwarfed by palatial new clubhouses nearby, including the United University Club on Suffolk Street which opened in 1826, and the Union Club on Union [now Trafalgar] Square which opened in 1827, and the Athenæum and Travellers Club buildings then under construction on Pall Mall. Consequently, a decision was made in 1825 to dispose of the site and build anew, making the most of the large new plots of land on Pall Mall, available from the recent sale of Carlton House.

The existing Charles Street clubhouse ended up being purchased by the new Junior United Service Club - set up for those who were on the waiting list for the United Service Club - and it provided their building until 1854, when it was demolished and they erected a clubhouse of their own on the site, which served them for the next 99 years.

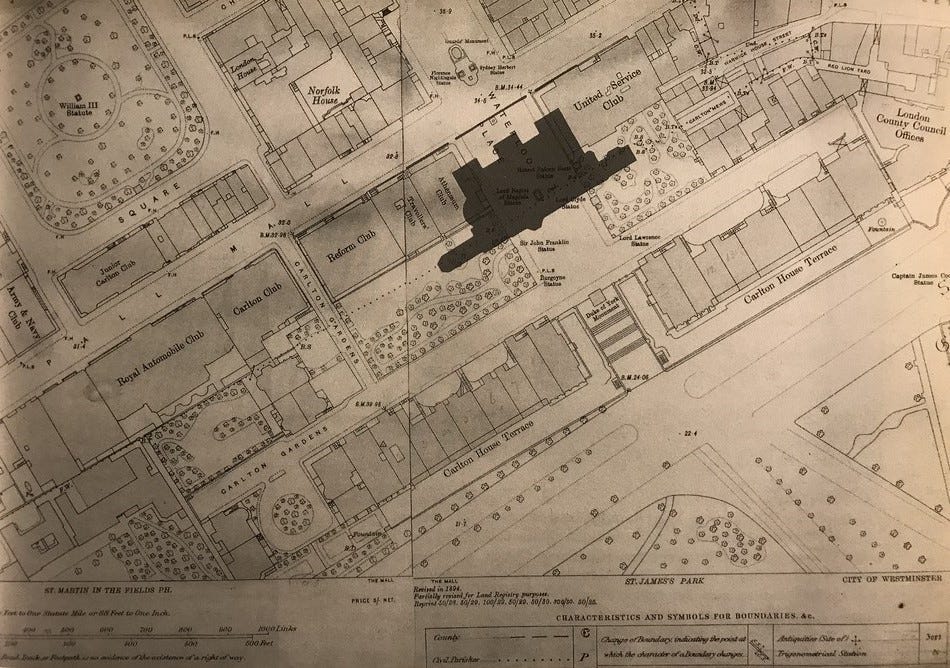

The former Royal palace of Carlton House, superimposed over an 1894 Land Registry map of the surrounding district. The United Service Club’s 1828-1975 clubhouse at 116-117 Pall Mall can be seen at the eastern end of the old Carlton House site. (Picture credit: Hugh Tait and Richard Walker, The Athenæum Collection (London: Athenæum, 2000), p. xvix.)

Pall Mall clubhouse

The Club built its new clubhouse at 116 Pall Mall, on the corner with Waterloo Place. For the architect, they commissioned the premiere architect of Regency London, John Nash.

Nash, who enjoyed the patronage of King George IV, was responsible for many of the most notable buildings of the era, including the nearby Regent Street that led up to the new building, which had originally been conceived as a grand triumphal approach to Carlton House. (Ironically, Carlton House was demolished in 1826, just one year after the completion of Regent Street.)

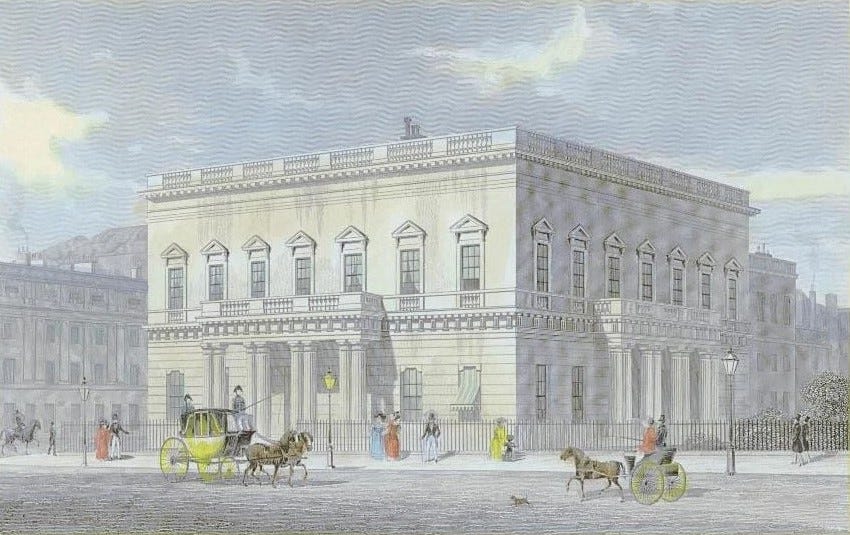

The Pall Mall clubhouse, as completed by John Nash in 1828. It retained this appearance until the 1858 refacing by Decimus Burton. (Picture credit: Thomas H. Shepherd, ‘The United Service Club House’, Louis C. Jackson, The United Service Club and its Founder (London: Sanders Phillips, 1931).)

Nash’s 1828 clubhouse represented a major escalation of Clubland architecture; an attempt to outdo recent clubhouses like the Travellers, United University and Union Clubs. Though its exterior was neoclassical, its interior was rooted in English country houses, as was common in clubhouses of the era.

In 1842-3, the Club commissioned Decimus Burton to make some minor alterations to the Club. Burton was exceptionally well-suited to the task: he was a disciple of Nash (who had died in 1835), and he had designed the Athenæum directly opposite the Senior, across Waterloo Place.

The modified clubhouse today (left), embedding Decimus Burton’s 1858-9 Roman-influenced alterations, and complementing Burton’s earlier Greek-influenced Athenæum (right) across Waterloo Place. (Photo credit: Canvass Events website.)

In 1858, the Senior at 116 Pall Mall acquired the adjoining building at 117 Pall Mall, and for the task of annexing this space and almost doubling the size of the clubhouse, they once again turned to Burton. According to Louis C. Jackson in 1937:

“Now that he was given his chance with the Senior, his first care was to embellish the rather plain exterior. He provided a frieze, also a large external cornice with a ballustrade over it, and widened the lower cornice. The window dressings were made more effective and the upper portico columns were fluted. He removed the columns of the west front and substituted a stone ballustrade for the area railings. He also found it necessary to replace Nash’s mastic stucco by Portland cement stucco.

“There is no doubt that the outside of the Club was considerably improved by his work, especially by the frieze”

The result of Burton’s work on both sides of Waterloo Place, in work done nearly three decades apart, was to create a neoclassical space, with the Greek-inspired Athenæum on one side, and the Roman-inspired United Service Club on the other side, each with their own frieze, columns and ballustrade, in styles both distinct and complementary.

A tinted colour photograph of the first-floor hall balcony in 1931, above the main staircase. (Picture credit: Louis C. Jackson, The United Service Club and its Founder (London: Sanders Phillips, 1931).)

Members and staff

The Club made much of the Duke of Wellington having been a founder member - he accepted an offer to join the new club, just five days before the Battle of Waterloo. In the ensuing years, the membership list read like a Who’s Who of generals and admirals.

In the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars, veterans did not only swell the ranks of the membership. They provided staff, too. In this respect, the Club proved highly influential on an employment practice which became very common in 19th century Britain, with the clubs looking to ex-soldiers and ex-sailors to staff these institutions.

The Club underwent a major change to its membership in 1892, when it abandoned the stipulation that only senior officers above the rank of Major or Commander qualified for membership. This relaxed some of its recruitment difficulties, but it continued to be the club most closely identified with senior officers.

A tinted colour photograph of the first-floor Library in 1931. (Picture credit: Louis C. Jackson, The United Service Club and its Founder (London: Sanders Phillips, 1931).)

Wider impact

I would suggest that the Club’s main contribution to club life - and this cannot be underestimated - was in bringing officers’ mess culture to clubs more generally, and through this, helping to regulate what we think of as the norms around club customs and service.

While there had been other military clubs before, such as the Guards Club founded on St. James’s Street in 1810, these were often dominated by subalterns, and the atmosphere could be boisterous and rowdy - more in keeping with the aristocratic hooliganism that could be a feature of the 18th century social clubs. By contrast, the emphasis at the United Service Club was on seniority and propriety; and along with the Athenæum opposite, it helped to popularise a more serious, sober idea of Clubland in the 19th century, in contrast to the frivolity of the 18th century.

A tinted colour photograph of the ground-floor Smoking Room in 1931. It had originally been the Coffee Room [dining room]. (Picture credit: Louis C. Jackson, The United Service Club and its Founder (London: Sanders Phillips, 1931).)

There was also the architectural legacy. Burton’s neo-classical piazza on Waterloo Place, with his construction of the Athenæum on one side and his refacing of The Senior on the other, and the uninterrupted row of three palatial clubhouses west of that from 1841-1940 (Travellers, Reform, and Carlton - with the RAC added on the end, from 1913) came to visually define ‘Clubland’ in print and film. By way of an indicator, from 1890-8, the Illustrated London News ran a five-part occasional ‘In Clubland’ pictorial supplement: the five clubs selected were (i) the Carlton, (ii) the Reform, (iii) the Athenæum, (iv) the United Service, and (v) the Travellers. In short, the United Service Club was seen as one of late Victorian London’s quintessential clubs.

The United Service Club’s four-page pull-out supplement from the Illustrated London News in 1894, as part of their occasional ‘In Clubland’ series. (Author’s own collection.)

Imitators

As well as the Junior United Service Club (1828-1953) referred to above, there were various other clubs inspired by The Senior, which took after their namesake. There was a Ladies’ United Service Club on Curzon Street (1872-1920), for the wives, widows, mothers and daughters of army and navy officers.

Yet it was in the colonial sphere that clubs most obviously emulated The Senior:

The Bengal Military Club opened in Calcutta in 1845, one of the earliest clubs set up by the British in India, changing its name to the United Service Club in 1853, and continuing until 1949.

Elsewhere in India, the Bangalore United Service Club was set up in 1863, and still exists today under its post-independence name, the Bangalore Club.

In Shimla, which the British declared the imperial “summer capital” of India in 1864, a United Service Club there had been founded the previous year, continuing until 1947, when the withdrawal of British troops after independence removed the Club’s membership base.

In Australia, the United Service Club Queensland was founded in Brisbane in 1892, and still exists.

Not all of these clubs followed the United Service Club’s lead in being for senior officers only (but then, neither did The Senior itself, after 1892.) However, they all emulated its model of a cross-services club. Closer to home, many others would follow this model, too, including the Oriental Club (1824-present), Army & Navy Club (1837-present), the East India Club (1849-present, whose original name was the East India United Service Club), Naval & Military Club (1862-present), Junior Naval & Military Club (1879-1939), and two unrelated Junior Army & Navy Clubs (1871-92 & 1911-68).

The main entrance to the clubhouse on Pall Mall filmed in 1956, as a location (doubling for the exterior of the Reform Club) in Around the World in 80 Days, with David Niven playing Phileas Fogg.

Decline and closure

For a club which stressed senior military officers, the end of the Second World War proved a serious setback: by way of illustration, in 1945 the British Army and Royal Navy respectively numbered 3.5 million and 860,000; by 1975, the figures were 176,000 and 74,000. (These tallies refer to total numbers, not to the much smaller number of officers.) The Senior therefore suffered not only from a serious curtailing of its potential recruitment pool, but its membership was overly dependent on pre-1945 officers, from when the armed forces were more numerous. By the late 1960s, these members were quite literally dying out.

Various mergers were undertaken, in an attempt to stave off the inevitable: The Senior absorbed the Junior United Service Club in 1953 (which brought in many very similar members); the Union Club in 1964 (which brought in several hundred civilian members for the first time); the Royal Aero Club in 1971 (which made it a truly tri-service club for the first time).

The Club was not helped by its building having been made a Grade I Listed building in 1970. As many clubs found in the mid-20th century, beyond the initial euphoria at the Listing being announced came a plethora of ruinously expensive repairs - for which the Club was now liable.

Eventually, amidst mounting costs and dwindling member revenue, the Club blamed the effects of inflation for being the final nail in the coffin, and closed its doors in 1975. The membership merged into the Naval & Military (“In & Out”) Club.

The clubhouse since 1975

The building was briefly leased to the Department for the Environment for several months of 1976-7, hosting planning hearings in its grand surroundings, before being put up for sale.

The lease on the building was sold to the Number 10 Club, then based at 10 Belgrave Square. The Club was a branch of the Institute of Directors (IoD) for UK company directors, that was flourishing with tens of thousands of members, and was actively seeking larger premises than its relatively cramped Belgrave Square townhouse. A deal was made with the freeholders, the Crown Estate, whereby the Number 10 Club would purchase The Senior’s lease for use by the IoD, as a professional set of premises for the Institute, while still offering some club-like facilities. With a view to respecting its Grade I Listing, a condition of the Crown Estate lease was the maintenance of the original fixtures and fittings of The Senior, including retention and upkeep of all the military portraits which still line the building. After some renovation to convert the building to its new use, it opened as the IoD in 1978.

Purists from The Senior would no doubt baulk at the idea of trade being carried out on their old premises, with co-working spaces and laptop lounges being common today- something that Anthony Lejeune bemoaned in 1979:

“What would the irasible veterans of Wellington’s army and Nelson’s navy say if they knew that their disapproving portraits now looked down on businessmen discussing trade? The Senior is perhaps the most serious - and socially symbolic - casualty yet in London clubland.”

Nevertheless, the arrangement has meant the preservation and ongoing use of a historic space that could have otherwise all too easily been sold off, dismembered and partitioned as so many other former clubhouses have been, as hotels, offices, private homes, private banks, overseas university campuses, or simply as vacant properties left rotting in central London.

The grand staircase of the former United Service Club, as it is preserved today. (Photo credit: 116 Pall Mall website.)

While the IoD is still a membership organisation, it is not run as a club, and so non-members can secure access to some parts of the building and admire the architecture: a tip for readers is that the large Carlton Brasserie and Lounge (which was originally the Coffee Room [dining room], and later the Smoking Room, running the full length of the rear ground floor of the building) runs a “grazing station” from 8am-6pm on weekdays, with unlimited tea, coffee and cake for a half-day or full-day fee. It won’t grant you access to the whole building, since many parts remain for IoD members only, but it will give you a glimpse of areas like the grand staircase, and it offers a comfortable place to park your carcass whilst sizing up the paintings, admiring the architecture, and looking out over Waterloo Place.

The Carlton Lounge of the Institute of Directors today, formerly the Coffee Room of the United Service Club. (Photo credit: 116 Pall Mall website.)

Further reading

Louis C. Jackson, The United Service Club and its Founder (London: Sanders Phillips, 1931).

__________, History of the United Service Club (London: United Service Club, 1937).

The seal of the United Service Club.

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

Seth, thank you very much for this edifying essay on a magnificent edifice! If I might humbly offer a couple of corrections for the record though, The Travellers Club building designed by Charles Berry was not completed until 1832. Also, the article notes “The Bengal Military Club opened in Calcutta in 1845, only the second club set up by the British in India…”. Actually, the first club to be set up by the British in India was the Bengal Club, in 1827 (originally known as the Bengal United Services’ Club!). This was followed by the Calcutta Golf Club in 1829 and the Madras Club in 1831, all of which are still extant today.

Small nits, I know, but hopefully they contribute something to the conversation, and constitute only very marginal corrections of what is otherwise a superb article. Thank you so much, and please keep it coming!