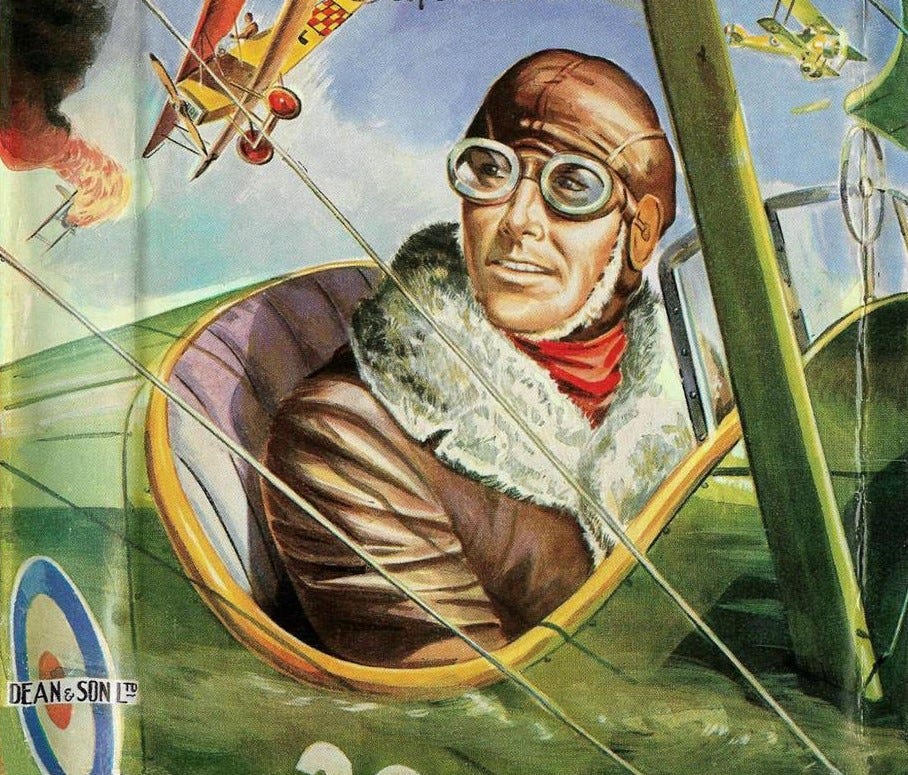

The ‘Biggles’ series, of nearly 100 novels and short story collections by Captain W. E. Johns, tells the adventures of archtypal square-jawed British air ace James Bigglesworth, known to his friends as “Biggles.” The best-selling tales, firmly in the ‘ripping yarns’ tradition, were published from 1932 to 1968, and fall into several distinct phases: cynical World War I air ace stories, free-wheeling inter-war capers, more straightforward World War II adventures, and a range of post-war ‘Special Air Police’ tales that could veer into espionage and detective fiction.

They have rather fallen out of fashion in recent decades, due to their archaic language and attitudes. Yet for generations raised on Biggles books, they bring to mind reliably exciting tales of derring-do, from a seemingly more innocent age. For those less familiar with them, they are usually the butt of endless jokes, not wholly unfanned by Johns’ often double entendre-laced book titles (who can forget Biggles Takes It Rough?), and his predilection for using the word “ejaculated” as a synonym for “said”, at almost every opportunity throughout the books.

Biggles, and his friends Algy and Ginger (and in the later stories, Bertie), can all be seen in the tradition of Richard Usborne’s ‘Clubland Heroes’ - a popular literary trope in the early 20th century, of morally upright, imperial British children’s heroes, whose values were represented by their all belonging to London clubs. David Cannadine has suggested this tradition extends to Ian Fleming’s literary James Bond.

And it obviously embraces Biggles, too. Mayfair clubs appear in 16 of the books. It is clearly stated several times in the books that Biggles is a member of the Royal Aero Club, and what little we see of his social life in London seems to revolve around it. For instance, in Biggles Defies the Swastika (1941), when he is undercover in Norway and has overpowered the German officer Schaffer, they have this exchange:

‘We shall meet again.’

‘Perhaps,’ smiled Biggles. ‘If we do I hope it will be after the war. Look me up at the Aero Club, and I’ll stand you a dinner in return for the use of your uniform.’

Information on Biggles’ club membership can be vague, thanks to Johns’ propensity for sparse prose - but a number of details can be fleshed out.

The Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club was described by its former Secretary in the 1940s as having a pioneering spirit:

“Here were the men who blazed the skies, pioneers whose names are history, like the De Havillands, Short Brothers, Handley Page, Hawker Siddeley, Fairey Aviation, Rolls and Royce, men who made he Royal Air Force the greatest striking force in World War II.”

The Club was established - originally as the Aero Club - in 1901, at the instigation of keen amateur balloonist Vera Hedges Butler, who the previous year had become one of Britain’s first women to pass the driving test. She first made the suggestion of a club for aviators while on a balloon flight, at 4,000 feet, suggesting a British equivalent of France’s Aéro-Club. She and her father the wine merchant Frank Hedges Butler became the founders, along with pioneering aviator the Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls - who was later killed in an air crash.

They began by meeting in an apartment at 4 Whitehall Court, next door to a range of other London clubs, including the nascent Royal Automobile Club. In these early days, as well as providing typical club facilities, the Aero Club would enter teams to compete in the races of the era. The Club’s object was:

“The encouragement of aero automobilism and ballooning as a sport, and to develop the science of aerial navigation in all its forms and applications.”

From 1910, they were granted Royal patronage, allowing them to change the name to the “Royal Aero Club.” It also began setting up a range of provincial Aero Clubs across the United Kingdom from the 1910s, which were formally affiliated, both giving the Club an instant form of reciprocation, and helping it to build a community of practice among qualified pilots.

3 Clifford Street, Mayfair, the home of the Royal Aero Club from 1916-33. (Photo credit: Buckley Gray Yeoman website.)

The Club’s first standalone clubhouse, from 1910 to 1916, had been at 166 Piccadilly; but this still pre-dated Biggles learning to fly in 1917. By the time he became a pilot, the Club was based at 3 Clifford Street (diagonally just opposite Buck’s), where it remained from 1916 to 1933. The Clifford Street premises are not described in the books (fewer than a dozen of the 98 books were set prior to 1933), but it can be inferred that he was already a member during part of the Club’s time in this location.

117-119 Piccadilly, with the Royal Aero’s old clubhouse at number 119 taking up the left half of the block. (Photo credit: Charles Watson, via the Historic England website, and the Listing for the building.)

In 1933, the Club moved to larger premises at 119 Piccadilly, and these are explicitly described in the stories. The building was the former home of the Royal Automobile Club - it had been their first full clubhouse from 1902-13, between moving out of their own apartment in Whitehall Court, and moving to their present palatial abode in Pall Mall. After the RAC moved out, the building had served for 20 years as the clubhouse of the Cavendish Club, before it was acquired by the Royal Aero Club in 1933. Like the Clifford Street building, it would have been conveniently located for Biggles, approximately 10-15 minutes’ walk from his Mayfair flat in Mount Street, which he often shared with Algy and Ginger.

The building was badly damaged by a high explosive bomb in December 1940, which destroyed its squash court and caused wider structural damage. The Club also suffered financially during the war, negotiating with its landlord a reduction in its lease. By the end of the war, it began looking for cheaper accommodation.

Londonderry House, home of the Royal Aero Club from 1947-61. (Photo credit: Ian Malpass-Scott.)

From 1947 until 1961, the Royal Aero Club moved to Londonderry House, at 19 Park Lane. The house was built around a 1760s-constructed mansion by James “Athenian” Stuart for the 4th Earl of Holderness, and was heavily redeveloped after its 1819 acquisition by the 1st Marquess of Londonderry. It benefitted from luxurious interiors, and its art holdings were considerable, including works by Canova, Bellini and Stubbs. But it was also in a desperately poor condition when the Club moved in, with only one working toilet in the whole building, and a ballroom ceiling which promptly collapsed.

The building had been offered to the Club by former Secretary of State for the Air the 7th Marquess of Londonderry, for a peppercorn rent of £25 a year, and the Club paying the building’s astronomical £10,000-a-year rates bill, while the Marquess continued to be able to use the premises as his London home. It was an amicable enough arrangement for the first couple of years: the 7th Marquess, a known Nazi sympathiser (and the real-life inspiration for “Lord Darlington” in The Remains of the Day), was living in some disgrace at his stately home of Mount Stewart in County Down, giving the Club a wide berth. But after his death in 1949, the 8th Marquess of Londonderry assumed the title and was an increasingly frequent presence in Londonderry House - not an easy situation, due to the 8th Marquess’ alcoholism and erratic behaviour, and he died of liver failure in 1955, aged 52. The Londonderrys sold the building for £800,000 in 1962 (around £25 million today), leading to its demolition, and the redevelopment of the site in 1965.

The displaced Royal Aero Club, meanwhile, had moved in 1961 to a space inside the Lansdowne Club, which gave them a museum for their artefacts, and their own bar. This Mayfair address, just off Berkeley Square, would have also been convenient for Biggles on Mount Street. And there is something all too appropriate about Biggles spending his later years, just before his mooted retirement in Biggles Does Some Homework (written in 1968, published in 1997), in a museum. The Club’s arrangement with the Lansdowne ended in 1968 - the year Captain W. E. Johns died.

We do not know, therefore, when Biggles died, and whether he would have taken in the Royal Aero Club’s painful last few moves. In 1968, the Club moved into the newly-opened Junior Carlton Club modernist office building on Pall Mall; but this arrangement did not last; and in 1971, it merged into the United Service Club further up Pall Mall. However, that closed down four years later, and its membership merged into the Naval & Military (“In & Out”) Club, then based on Piccadilly. The Royal Aero Club still exists as a co-ordinating and regulatory body for recreational aviation, but has long since ceased to provide club facilities. Biggles, born in 1899, would presumably have died before most of these developments.

The Royal Aero Club in the canon

It is strongly implied throughout the series that Biggles, Algy and Ginger are all members of the Royal Aero Club. For instance, the opening of Biggles in the South Seas (1940) states:

It was a perfect morning in early spring, when Major James Bigglesworth, better known to his friends as Biggles, with his two comrades, the Honourable Algenon Lacey, M.C., and ‘Ginger’ Hebblethwaite, turned into Piccadilly on their way to the Royal Aero Club where they had decided to take lunch. They walked slowly on the Park side of the great thoroughfare, enjoying the sunshine, and it was with some reluctance that they finally crossed over to the Club entrance.

They are clearly regulars, used to the rhythm of the Club’s dining operation, for Biggles observes, “If we go in right away we can get a table near the window,” and after being joined by a friend, “they went in through the swing doors and settled themselves at a window table laid for four.”

Biggles is also given to simply popping in. In Biggles Buries the Hatchet (1958), Johns describes an impromptu visit by Biggles:

The others had gone on home, but he had taken a taxi and broken his journey at the Royal Aero Club, in Piccadilly, not for any particular reason but merely to see if any old friends were passing an hour or two at this natural rendezvous for professional air pilots, past and present. He saw no one with whom he was on familiar terms, but spent a little while in the reading room skipping through the foreign aviation journals. It was dark when he left.

The main staircase of the now-demolished Londonderry House on Park Lane, home of the Royal Aero Club from 1947-61. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Foundation; colourised using the Kolorize.CC app.)

In Biggles Follows On (1952), it is clearly implied that Air Commodore Raymond is also a member of “the club”:

The Air Commodore was not in his office. Biggles went to his home, and caught him just as he was leaving for the club, where he usually dined

and Biggles joined him “in a quiet corner of the dining-room.”

The Club was also a way of keeping tabs on other aviators. In Biggles in Africa (1936), when Felix Marton wanted to hire Biggles to investigate the disappearance of his aviator son, Biggles’ first step before even meeting with Marton was to place some background queries with the Club:

‘I’ve just been speaking on the telephone to the Secretary of the Royal Aero Club to refresh my memory with the circumstances of - but never mind that.’

Biggles would also avail himself of the Club’s written records on other pilots. In Biggles Works It Out (1951), he investigates a vanished ex-pilot, and notes that:

‘his name had been erased from the list of members of the Royal Aero Club. After that he had faded out of aviation circles. His present address was unknown.’

To Biggles and his friends, the Club was also a matter of personal identification and expression, which they felt gave them recognition and standing. In Biggles & Co (1935), we read of Algy’s time in captivity:

For a long time, while the sun sank and the white light of day faded slowly to the purple of evening, he employed himself by composing a letter which he would insist that the Royal Aero Club should send to the German Government when he got back, protesting, in sometimes violent and sometimes plaintive language, against the treatment that had been meted out to him as a stranger in a foreign land.

The Club also appears to be something of an anchor in Biggles’ career, and if anything, his visits appear to have become more frequent in the later stories. In Biggles Flies to Work (1963), he mentions, “I saw Sammy [Marsden] in the Aero Club a few weeks back”; while the denouement to Biggles and the Gun Runners (1966) notes, “one day he ran into Sandy [Grant] at the Royal Aero Club.” One of the very last books in the series, Biggles and the Deep Blue Sea (1968), set in the present day, notes Biggles “and Algy had been home for nearly two months when they happened to drop into the Royal Aero Club for lunch,” clearly still members after at least three (and possibly five) decades.

The Royal Aero Club’s role in issuing Aviator’s Certificates

From 1910 to 1945, the Royal Aero Club had a key official regulatory role in aviation: as the recognised body overseeing aviation, it issued all Aviator’s Certificates to newly-qualified pilots. The overlap with the pilot community, at a time when aviation was a small but growing field, was therefore considerable.

(This role for the Club can be seen as a parallal to the early role of RAC in the regulation of motoring, as a new sport involving a new technology - it was thought it was best left regulated by the enthusiasts who best understood it, and while a club did not have the official recognition of a Learned Society, it was thought to carry some authority - especially after the granting of the “Royal” title.)

An aviator’s certificate, of the kind issued by the Royal Aero Club from 1910-45. (Photo credit: RAF Museum website.)

We actually see this role outlined at the start of Biggles Hits the Trail (1935). The occasion is a small dinner party at Biggles’ apartment as he makes a tongue-in-cheek speech to his two comrades:

‘Gentlemen,’ resumed Biggles, with a withering glance at Algy, ‘I feel I should fail in my duty if I allowed this auspicious occasion to pass without a few words on the reason for this festive gathering to-night. As you are aware, we sent our guest of honour - who, as we are all friends, I will call by his apt if undignified pseudonym, Ginger - to Brooklands Aerodrome for a course of instruction in the art of flying, and its allied subject, ground engineering. Last week he was tested for his Pilot’s “A” Licence, and yesterday notification of its award was made by the Royal Aero Club.’

‘Hear, hear! - hear, hear!’ exclaimed Algy enthusiastically.

The Aviator’s Certificates later become a plot point in ‘The Case of the Lost Souls’, a short story in Biggles of the Special Air Police (1953). Investigating the pilot Lucius Landerville, Biggles tells Ginger:

“I fancy I know where I can look him up.”

“Where?”

“At the Royal Aero Club.”

Biggles follows up, and explains how he tracked down the suspect:

“Forty years ago, ballooning was still a popular sport…At the Aero Club, where aeronauts’ certificates were issued as pilots’ licences are today, I found that forty years ago two of our leading balloonists were brothers named Landerville. The trail was getting hot.”

In this tale, Biggles also finds the Royal Aero Club a fruitful source of human intelligence, observing, “A fellow at the Club told me that at one time he used to run a popular bar in Paris.”

Cutting through red tape

The Royal Aero Club also opened doors to overseas flying, cutting through red tape. Biggles makes this clear in Biggles Flies Again (1934), when he is asked if he had been given permission to fly over Persian airspace:

‘No, we haven’t,’ he confessed, ‘but we do not anticipate any difficulty. Most National Aero Clubs extend their courtesy to foreign pilots.’

The earlier books also fleshed out the regulatory role of the Club in other ways. They often contained contextual footnotes and asides from Captain W. E. Johns, as when Biggles remarks in Biggles and the Black Peril (1936):

‘I don’t see why it should be if our papers are in order. We’ve got our passports. We can get carnets from the Aero Club, and set off on an ordinary air tour. Who is going to say that we aren’t just air tourists?’

Johns elaborates on this with a footnote informing the reader:

Touring abroad by air is not merely a matter of ‘Go as you please.’…there is the Customs’ Carnet (pronounced carnay) which is issued by the Royal Aero Club to avoid difficulties with customs officials in the matter of import duties.

The RAF Club

It is often assumed by fans that Biggles must have been a member of the Royal Air Force Club. This was established in 1918, as the successor to the short-lived Royal Flying Corps Club at 13 Bruton Street (1917-18); and has since 1922 been located at 128 Piccadilly, next door to the Cavalry Club (now the Cavalry & Guards Club).

Yet there is slender evidence in the canon for Biggles having belonged to the RAF Club. The reasons for this may have been social as well as practical. In addition to the Royal Aero Club having played a regulatory role in pilots’ certificates, it was also the more prestigious club, for qualified aviators. The RAF Club was not set up until nearly two decades later, and it was conceived as much more of a mass-membership club, embracing plenty of ground crew as well as flyers.

It is unclear whether Biggles’ Mayfair apartment was rented or owned; and if the latter, whether he had bought it himself or inherited it. But notwithstanding such an expensive address, pilots were not especially well-remunerated in either the RAF or in the police; and the inter-war stories hint at recurring financial difficulties, with Biggles being erratically employed or under-employed - in Biggles in Africa (1936), for instance, a pyjama-clad Algy grumbles, “There’s nothing much to get up for, is there? None of us has done a day’s work for weeks.” This makes it much less likely that Biggles or his friends would have sustained multiple club memberships, especially among two such similarly-themed clubs, so close to one another.

Yet Biggles was far from unaware of the RAF Club’s existence. At the beginning of Biggles in the South Seas (1940), his friends and he bump into an old acquaintance, ‘Sandy’ Macaster, smoking a pipe by the main staircase of the Royal Aero Club. When they ask him if he has had lunch yet, he replies:

‘No. I was just thinking of going into the Air Force Club for a change.’

Biggles responds with an invitation for Sandy to join them for lunch in the Royal Aero Club instead.

Biggles and his friends also show an awareness of the RAF Club in Biggles on the Home Front (1957 - though its placement of the Royal Aero Club on Piccadilly means it must have been set no later than 1947). Biggles is investigating a package left on the park side of Piccadilly, and he quizzes Ginger:

“Do you remember the buildings on the other side of the road?”

“The R.A.F. Club and the Royal Aero Club take up quite a bit of ground. They’re the only two I can recall. One can usually find room to park a car there.”

“I wasn’t thinking so much of parking space as the buildings.”

“The Clubs?”

“Yes.”

“What’s remarkable about that?”

“If the car incident had to be considered alone I’d say nothing. But when I tell you that the man who met me under the clock was wearing an R.A.F. tie you’ll get the drift of the lines on which I’m thinking.”

Ginger’s eyes opened wide. “He might have gone to one of the clubs to meet someone.”

“It’d be reasonable to suppose he’d park the car somewhere near his destination, if only to save walking.”

“Why not try the clubs to see if he’s there?”

“Not likely. He might see me, in which case he’d certainly wonder how a shady character like Ted Walls came to be a member of the club.”

Later in the book, Biggles observes, “I feel pretty sure now that he went either to the Air Force Club or the Aero Club after pinching that car.” He clearly sees both clubs as part of the same realm.

This is also reflected in Biggles and the Plane That Disappeared (1963), when Biggles tries in vain to trace a vanished pilot, establishing “He was not a member of the R.A.F. Club, or the Royal Aero Club.” But it is clear that Biggles is not relying on the internal records of either club, but on “The files and records at Scotland Yard.” It is therefore no evidence of membership of either club, just of his again seeing the two clubs as part of the same world.

The RAF Club at 128 Piccadilly, a building which it has occupied since 1922. (Photo credit: Nikon Owner blog.)

While none of this denotes the RAF Club having been Biggles’ club - merely a club near to his own, of which he was aware - it is distinctly possible that the RAF Club was Bertie’s club.

Bertie’s club

From the World War II adventures, the threesome of Biggles, Algy and Ginger becomes a foursome, with the addition of Bertie - Bertram Augustus Lissie, “The Lord Lissie” (although he seldom uses the title). We know from Biggles Looks Back (1965) that his passport lists his occupation as “gentleman.”

Bertie’s country seat is given as Chedcombe Manor, so unlike Algy and Ginger - who share Biggles’ Mayfair flat - he would have needed a place to stay in town. Given his background, it could be speculated that it was a more traditional, aristocratic club. However, there is evidence that it was the RAF Club. In Biggles Fails to Return (1943), when Biggles (as the title suggests) fails to return, we are told:

Over lunch, and afterwards, in a secluded corner of the Royal Air Force Club, in Piccadilly, Algy, Bertie and Ginger, discussed the situation that had arisen.

This could be read as proof that all three pilots had joined the RAF Club. Yet the nature of the conversation as described hints at a different dynamic. The other two pilots are completely unfamiliar with Monaco, but not Bertie:

For several years he had gone there for the ‘season’ as a competitor in the international motor-car race called the Monte Carlo Rally. He had competed in the motor-boat trials, had played tennis on the famous courts, and golf on the links at Mont Agel. He had stayed at most of the big hotels, and had been a guest at many of the villas owned by leading members of society. As a result, he not only knew the principality intimately, but the country around it.

In other words, Bertie is holding court, and is almost certainly hosting this gathering. It is therefore likely that he was the hosting member.

Bertie’s membership of the RAF Club would doubly make sense, given its generous bedroom accommodation (with over a hundred bedrooms - making it easier than many other London clubs to book at short notice), and his rural base.

Conclusion

Biggles, Algy, Ginger and Air Commodore Raymond were all members of the Royal Aero Club. Biggles and Algy most likely joined when they became pilots late in World War I (or shortly thereafter), when it was still based in Clifford Street; and it was probably by the time it had moved to Piccaddilly that the much younger Ginger joined it, upon gaining his Aviator’s Certificate. They remained with the Club for the rest of their careers, through its moves to Park Lane and then within the Lansdowne Club. Bertie, by contrast, was most likely a member of the RAF Club - allowing the four to rotate hospitality between the two establishments.

Bibliography

Captain W. E. Johns, Biggles Hits the Trail (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1935).

__________________, Biggles and the Black Peril (London: John Hamilton, 1936).

__________________, Biggles & Co (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1936).

__________________, Biggles in Africa (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1936).

__________________, Biggles in the South Seas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940).

__________________, Biggles Defies the Swastika (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1941).

__________________, Biggles Fails to Return (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1943).

__________________, Biggles Works It Out (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1951).

__________________, Biggles Follows On (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1952).

__________________, Biggles of the Special Air Police (London: Thames Publishing, 1953).

__________________, Biggles on the Home Front (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1957).

__________________, Biggles Buries the Hatchet (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, 1958).

__________________, Biggles Flies to Work (London: Dean & Son, 1963).

__________________, Biggles and the Plane That Disappeared (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1963).

__________________, Biggles and the Gun Runners (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, 1966).

__________________, Biggles and the Deep Blue Sea (Leicester: Brockhampton Press, 1968).

__________________, Biggles Does Some Homework (privately published: Norman Wright, 1997).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

Thanks to you for all this information about a world of which I have hirtherto had no knowledge.

May I ask - are all these clubs still very ‘snobby’, or, in the light of apparently challenging times, are some of them welcoming of new members?

Thanks once again.