Around the World in 80 Days, Part 2 - The 1956 film

This is Around the World in 80 Days week. That’s right, with its depiction of the Reform Club being so iconic, I’m going to do a separate post for 6 days this week, each one looking at a different version of Around the World in 80 Days, and how it depicts the Reform Club.

Michael Anderson’s 1956 epic of Around the World in 80 Days, starring David Niven as Phileas Fogg, is still one of the best-known versions of this tale. Yet while much of the film is given over to spectacular location filming, the portrayal of the Reform Club leaves a lot to be desired.

Exterior

The exterior was filmed on the Pall Mall entrance of what was a real club, four doors down from the Reform Club: the United Service Club, aka “The Senior”, for senior army & navy officers. That building still stands today, as the Institute of Directors.

Despite recognisably having bona fide clubhouse architecture, the United Service Club didn't look much like the Reform Club. By the 1950s, the Reform had modern touches outside the building like Belisha beacons directly in front of the entrance, making it very difficult to convincingly portray as a Victorian-era setting.

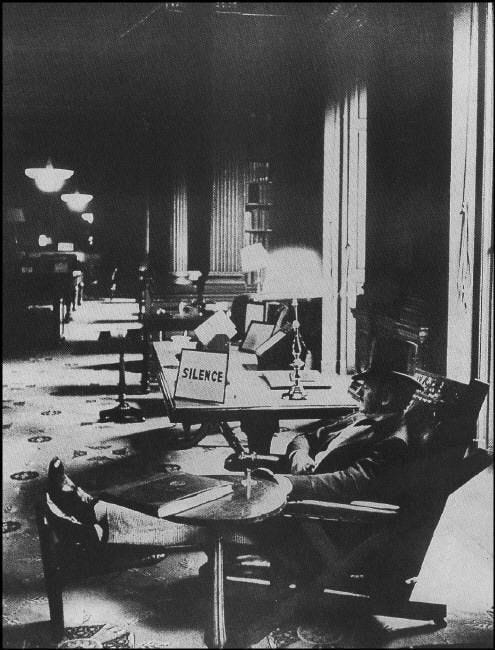

David Niven, in costume as Phileas Fogg, in a publicity photo taken in the real-life Reform Club. This image does not appear in the film.

Interior

The interiors were entirely filmed on a studio set. David Niven did, however, take several promotional photographs inside the real-life Reform Club, in costume as Phileas Fogg (see above).

While it has a lot of Clubland touches, the studio set bears absolutely no resemblance whatsoever to the Reform Club at all. Around the World in 80 Days (1956) had a highly fragmented production, and was reportedly filmed across 112 locations in 13 countries and 140 sets; but I suspect the sets for the Reform Club were shot in an English studio, judging from the number of actors hired who were UK-based in the mid-1950s. (Finlay Currie, Trevor Howard, Robert Morley, Ronald Squire, Basil Sydney, etc.)

Before we even get to the interior decor, the Georgian townhouse opposite glimpsed through the front entrance’s backdrop painting is all wrong. There is actually a short connecting road running from Pall Mall into St. James’s Square that should be more or less visible from that perspective (which is technically counted as part of the Square for the purposes of street numbers); and the angle of the building opposite is askew.

The porter's lodge (which, curiously enough, the porter isn’t actually inside as the scene plays out) looks nothing like that of the Reform Club’s. It seems much closer to that of the Garrick Club, with its glass cage.

And the pale-blue-with-black-trim colour scheme does not resemble the Reform Club at any time - though some superficial resemblance in the columns makes me wonder if the set designers worked off black-and-white images of the interior, without knowing the colour palettes involved.

The set cunningly manages to combine the outer ‘porter’s lodge’ area with an inner main ‘club room’ lounge area just beyond. As a studio set, it is very economical.

But no London club is laid out like this. They typically have a lobby or atrium or staircase beyond the porter’s lodge, rather than any Smoking Room-type setup located so immediately close to the front entrance. If they followed the film’s layout, it would make for a very ‘busy’ area lacking in privacy, when the film emphasises that it is supposed to be a place of silence.

In the real Reform Club, someone coming up the steps through the main entrance, past the porter’s lodge and into the main atrium would be faced with this, the central lobby. Note the completely different layout, design, materials and colour scheme.

Steps are another shortcoming of the film’s studio set - presumably for budgetary reasons. The set’s floorplan is completely flat.

The real Reform Club has steps up from the street to the main entrance, steps from the porter's lodge to the central Saloon, then a huge, ornate staircase up to the Smoking Room on the first floor. Indeed, one of the rejected architects’ plans for the Reform Club building, laden with a succession of staircases, prompted the comment that it was “Curiously preoccupied with ascent.” This may be said of the final building as well.

The paintings adorning the walls of the set are also somewhat ‘off.’ The real Reform Club was (and is) a ‘mausoleum’ to the Whig and Reformist politicians of the 1830s-1850s. However, the film’s studio set went for generic British aristocrats on the walls, with some dating back to the 17th century - I suspect salvaged from the sets of other films.

On the left we can see the Reform Club's members in the film playing whist in the ‘card room’ (actually the same set filmed from a different angle).

You can see how it compares to the real Reform Club card room on the right. (Or rather, how it doesn’t!)

The film set’s fireplace on the left is a fine piece of design, with impressive decorative mouldings. But again, it bears no resemblance to the real thing on the right - Charles Barry’s Reform Club fireplaces are smaller, with small freestanding clocks atop them, rather than embedding a giant clock.

Silence

The opening Reform Club scene extracts a great deal of comic value from the club being a place of silence - a trope already popular in films like Top Hat (1935). But while “silence rooms” were regarded as a distinctive feature of clubs, they were by no means typical - clubs are, after all, first and foremost social organisations, and so if a club had a silence space at all (and many did not), it was restricted to only one or two rooms of the clubhouse.

It therefore makes no sense whatsoever for the main room in front of the entrance (which surely functions as a lobby of sorts, as members have to cross it to access the rest of the Club) to also be a place of silence, and yet for it to be a place where members also play cards and converse. The main thing dictating these contrasting uses is the budget, and the need to have just one set performing many functions.

Dress

In the film’s finale, it is a nice period touch having the members in white tie and tails at 9pm (although it is broad daylight outside), presumably having been at dinner - earlier, they were shown in the Club in daywear. It emphasises Fogg’s eccentricity in turning up in his loungewear (not forbidden, as clubs didn’t have dress codes until the 20th century, and he is still allowed in - but it’s certainly considered unusual).

The servants’ livery is actually very well-researched. Court dress-type servants’ uniforms were in use at the Reform Club until the end of the 19th century; and the buff-and-blue colour scheme is a nice nod to the Whig followers of the legacy of Charles James Fox. This is exactly what at least some of the Reform Club’s servants would have worn in the 1870s. (Precise choice of staff uniforms depended on the exact role performed.)

Women

Now we get the film's biggest sin of misrepresentation, which was not in the original novel. A member exclaims:

“Great Caesar's ghost! A woman - in the Club!”

This would not have happened. While the Club did not elect women as members until 1981, women guests had been frequenting the Reform Club as visitors since the building opened in 1841. The film is set in 1872. Indeed, there are prints of women frequenting the building in the late 1860s.

The Reform Club in 1841 - one of many contemporary prints showing plenty of women guests in the Club. No-one appears to be exclaiming, “Great Caesar's ghost! A woman - in the Club!”

Wider accuracy

Interestingly, there appears to be a club cat (part of the film’s boast about the number of animals used in filming). This is doubtful. The Reform Club rulebook of the time had a ban on dogs. Club committees typically interpreted this to mean a ban on other pet-type animals.

I have been fairly harsh about the accuracy of the set’s overall look - it really seems it was designed by someone who'd never seen the Reform, and worked off black-and-white photos of other club interiors - but the furniture has much more verisimilitude. It has that low centre of gravity of club furniture, ideal for reclining.

However, the view from the back window on the right is non-sensical. The rear windows would open onto the Waterloo Gardens at the back shared with the neighbouring Travellers Club and Athenaeum, with Carlton House Terrace in the far distance. There is no wall jutting out at right-angles from the Reform Club building, it is shaped like a square.

I suspect they just wanted to keep the set design uncomplicated, by adding in a wall, so that they did not have to insert a painted backcloth.

Conclusion

I am enormously fond of this film classic, with which I grew up, and which I have often watched while travelling around the world.

But overall, this is one of the least accurate renderings of the Reform Club; and more than any other, it is to blame for the common misconception that women weren’t allowed to set foot in the Reform in 1872.

(This piece was adapted from an old Twitter thread I wrote on the topic three years ago. This is Part 2 of my 6-part look at six different versions of ‘Around the World in 80 Days’, starting yesterday with a look at Jules Verne’s original novel.)

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.