Around the World in 80 Days, Part 6 - the 2021 mini-series

This is Around the World in 80 Days week. That’s right, with its depiction of the Reform Club being so iconic, I’m going to do a separate post for 6 days this week, each one looking at a different version of Around the World in 80 Days, and how it depicts the Reform Club.

For this final part, I look at the latest television adaptation of ‘Around the World in 80 Days’, aired by the BBC in 2021. Although the setting obviously spanned the globe, for budgetary reasons the series was mainly filmed in two countries doubling for the rest of the world: South Africa and Romania. And the interiors and exteriors of the “Reform Club” were filmed in these two countries respectively.

The Reform Club interiors were filmed in Cape Town City Hall. The dimensions are very different to the real-life Reform Club, with far higher ceilings in the clubrooms, not to mention the presence of stained glass windows. To make it more plausible as a club, the interior was heavily redressed with the insertion of fake pillars, bookcases, and club furniture.

This is what the space in the Cape Town City Hall normally looks like, without all the ‘clubroom’ redressing. The room presents some design challenges, though. There is no real parallel to a balcony level inside a clubroom of the Reform Club - only the balcony over the central saloon under the main atrium. So the inclusion of a balcony in a smoking room seems a bit incongruous.

The pillars (which on closer inspection look to be made of moulded plastic!) are a fairly good reproduction of the pillar design which punctuates the Reform Club, with the dimensions clearly modified to fit this room. The first episode credits the Reform Club for their assistance.

For the armchairs, we revert to the “generic club-type armchair” design so often seen in period dramas onscreen. Although it looks elegant, this design of wingback leather armchair, so popular in the Georgian period, wasn't really to be found in early Victorian clubhouse design like the Reform Club, which favoured lower-slung armchairs with low centres of gravity, for lounging in - a Clubland trend which was exacerbated by the 1870s, when this story is set.

There are some nice prop period pieces, such as the light fittings inserted in the background, closely modelled on those found in the Reform Club - although it is left ambiguous as to whether they are gas (as they should have been for this period, with Britain’s first gaslight exchange two doors away, on Pall Mall) or electric (as they would later be).

Where this depiction of the Reform Club really starts to fall short is in the choice of art. The designers went for a generic “Best of British” selection of busts; here we see Shakespeare & Queen Victoria, the latter of whom incidentally looks far too old in her bust for this setting - they seem to have used an 1890s bust of an elderly Queen Victoria, for a story set in 1872.

As it happens, there is a bust of Queen Victoria in the central saloon of the Reform Club (over the fireplace, in the glass window through to the Coffee Room, facing anyone who comes in through the main entrance). But it is of her as a young Queen, in 1837.

But the wider incongruity is that the bust of Victoria is the exception, rather than the rule. All the other busts (and paintings) are of Whig, Reformer and Liberal politicians the Club was associated with from the 1830s to the 1850s. There is no Shakespeare. This club was built as a parallel Establishment, in the Whig, Radical and Reformer tradition - more Roundhead than Cavalier. (Cromwell had a huge personality cult among Victorian Liberals.)

And that is my criticism of the set dressing, not found in the original room, which makes up most of what we see of the Reform clubroom. It’s not bad, with nice touches like newspaper stands and period rugs - but a lot of it is rather generically “We got this as a Victorian prop from the storeroom or an antiques shop”, rather than having much to do with Victorian Clubland, or the Reform Club in particular. And some of the features are decades out. The 1989 mini-series was a lot more accurate, in using the real clubhouse next door as a filming location.

On the other hand, one of the stronger areas is the depiction of the servants’ area and kitchen. This was not a side of club life seen in earlier period dramas.

Some of the details are hard to make out in the gloom, but it is fairly close to the austere atmosphere below-stairs, where little money was spent on decor.

The Reform Club's kitchens, designed by entrepreneurial celebrity chef Alexis Soyer, were considered the foremost, trend-setting kitchens of their day, with a revolutionary production-line layout & no expense spared. Guided tours were given.

But unlike the stately clubrooms above, they weren’t “decorative.” They served a practical function.

When the series was aired, it generated some vocal criticism for being “woke”, with “stunt casting” of black actors in a period piece. I don’t think this criticism was justified. Victorian London was a global metropolis. London club servants came from all over the world; as indeed did club members. There were non-white members by 1872. If anything, the casting of black actors in this production arguably did not go far enough - in that they were only cast as servants. But they could have plausibly played members in 1872, too.

Nevertheless, I think it’s welcome that what we saw onscreen represented the London of 1872 - a port city at the centre of a global empire, with people drawn from all over the world. And club servants had been disproportionately recruited from London’s immigrant populations since at least the 18th century.

On the topic of diversity, we yet again see the repetition of the “No women in the club!” trope, which comes from the 1956 film (not the novel), and was again repeated in the 1989 mini-series. As I wrote before, although women were not allowed to join the Reform Club for another 109 years, they had been allowed as visitors to the Club since at least the 1840s, and there are multiple depictions of women visitors by the 1870s.

For the main staircase and lobby of the Reform Club, Cape Town City Hall was still used, with minimal redressing of its main staircase (left). It was adequate for its purpose for a quick scene; but to the trained eye, clearly represented a later style of late Victorian colonial architecture; built in 1900-5, over 60 years after Barry’s Reform Club.

Apart from the addition of a desk for the porter at the foot of the stairs, there was little attempt to redress the staircase, seen in its ‘natural’ state in the centre. It’s a very nice staircase. But it looks nothing like the Reform Club’s staircases (right). The Reform has a few (external) steps up to the porter's lodge, a few steps more up to the ground floor; then across the saloon and left to a very grand, but narrower, covered, carpeted staircase.

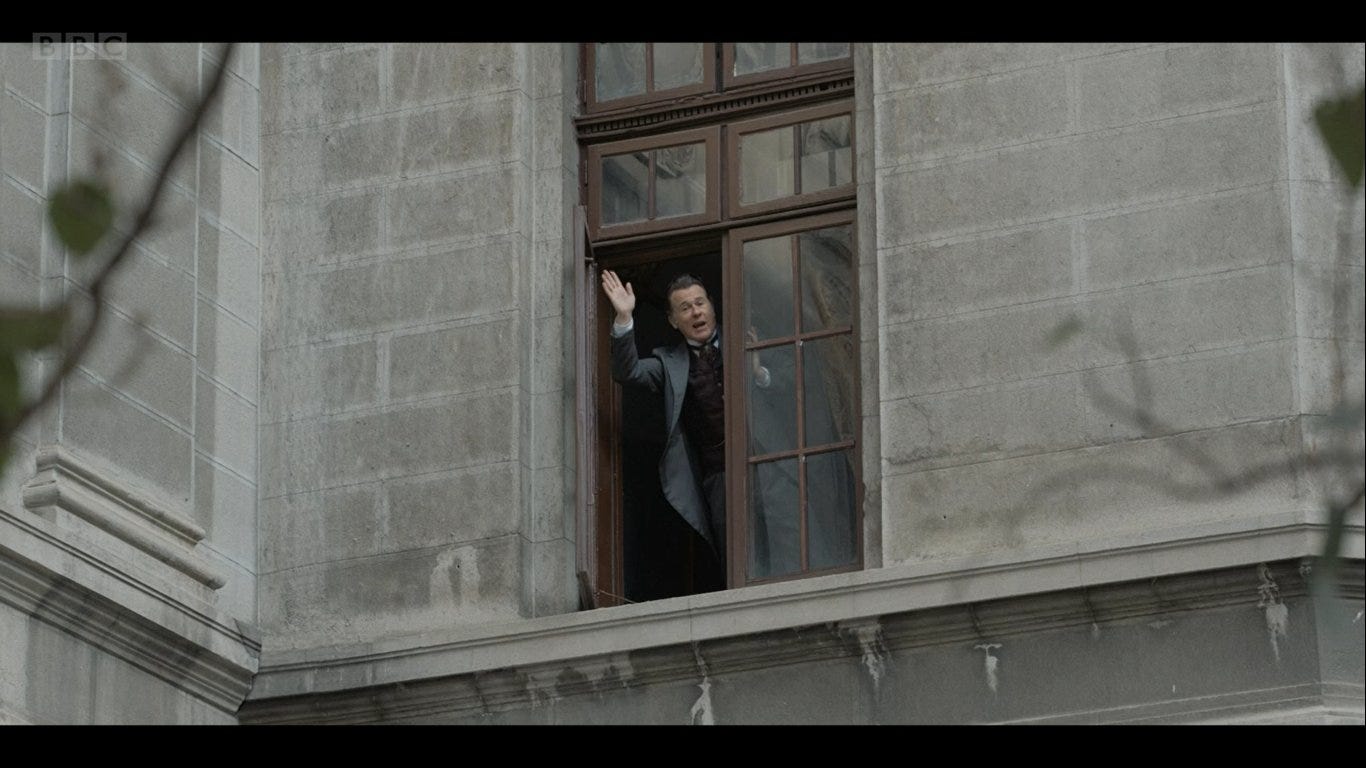

The exterior is a mystery to me. From the lighting, I'd guess somewhere in Romania rather than South Africa, but could it even be in England? I have no idea - all suggestions most welcome!

It's a very ornate building - far more ornate than the real Reform's exterior (whose porous stone is also very prone to being blackened by the London air, needing regular cleaning every few years - the building used looks much cleaner!)

And whereas the Reform basically has a box shape, the building used has wings jutting out in front (as well as very different windows).

As with the 1989 mini-series with exteriors were filmed off Chancery Lane, they took the trouble to put a club plaque outside, to enhance the illusion.

And as a final touch, I mentioned that the first episode credits collaboration from the Reform Club, even though no filming was undertaken there. The real Reform Club seal is, however, seen on the flag outside (and on the plaque by the front door).

The Reform Club’s seal is also seen in some of the interiors, as with the stand which houses a drinks cabinet (though this item of furniture doesn’t much resemble the Reform’s drinks trolleys, which are shorter).

In the real Reform Club, the seal tends to be inset within the architecture of the building itself, throughout the Club - for instance, it can be seen above the pillars in the saloon.

Conclusion

I enjoyed the latest adaptation. It took considerable liberties with the novel, but so did every other version. And while the original novel has some wonderful moments, it also contains plenty of vague passages lacking in drama, and so adaptations have often benefitted from making ‘improvements’ of their own. This is why I like the 1989 and 2021 versions, for all their flourishes. (Though we’re not even going to go anywhere near the 2004 atrocity - not least because it doesn’t feature the Reform Club, substituting it with a ‘Royal Academy of Science.’)

As for the representation of the Reform Club in this latest version, I found it…middling? Considerable effort, research and collaboration had clearly gone into it, especially in reproducing the pillars, and making use of the club seal. Yet parts of the building and its dressing did look rather clumsy, and off-period. There really is no excuse for an 1890s Victoria bust appearing in 1872…

If I am to decide the between the versions, for their depictions of the Reform Club: apart from the brief glimpse of the real Reform Club at the start of Michael Palin's modern-day journey in 1988, the most realistic of these screen renditions was in...the 1983 children's cartoon ‘Around the World with Willy Fog’!

(This piece was adapted from an old Twitter thread I wrote on the topic three years ago. This is the final part of my 6-part look at six different versions of ‘Around the World in 80 Days’; previous articles have looked at Jules Verne’s original novel; the 1956 film adaptation; the cartoon adaptations; the 1989 mini-series; and the 1989 travelogue.)

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.