Scores of London clubs were bombed throughout the Second World War. One of the highest-profile casualties was the Carlton Club. The Carlton - named after its first clubhouse in Carlton House Terrace - was founded in 1832 as the official club for the Tory Party, and mixed social facilities with practical political functions, including electioneering work and whipping operations.

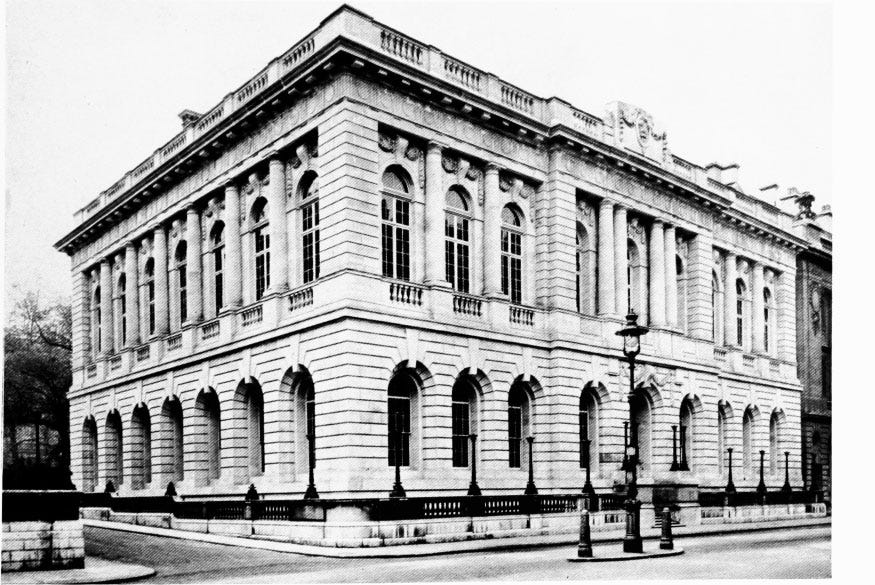

Sir Reginald Blomfield’s 1923-4 alterations to the façade of the Carlton Club, pictured in 1927. Aside from a darkening of the stone due to the London pollution, its external appearance was largely unchanged in 1940. (Photo credit: 'Plate 115b: Carlton Club, Pall Mall', in F. H. W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James’s, Westminster, Part 1 (London: HMSO, 1960).)

The Carlton Club in 1940

I have previously looked at the range of buildings occupied by the Carlton from 1832 to 1940. Since 1836, it had occupied a large site at 94 Pall Mall, next door to its great Liberal rival the Reform Club, from which it was separated by the narrow alley of Carlton Gardens. It remained a political powerhouse for Conservative politics - famously hosting the Carlton Club meeting of 1922 which ousted the Lloyd George coalition government - and through the 1930s, Winston Churchill had used the Club as a backbench Tory MP, lobbying his colleagues over issues from India to appeasement.

Like all clubs, the Carlton in 1940 was already hit by the privations of war; most notably with food rationing, particularly the stipulation which prevented any meal from costing more than 5 shillings. It was also impacted by the conscription of its younger members, though its demographic meant that many members remained above conscripting age, or else engaged in London on vital war work. These difficulties did not, however, stop the Club’s members from continuing to rally round and use the Victorian facilities of its opulent Smirke building, even if they were in diminished circumstances. This continued through the first month of the Blitz.

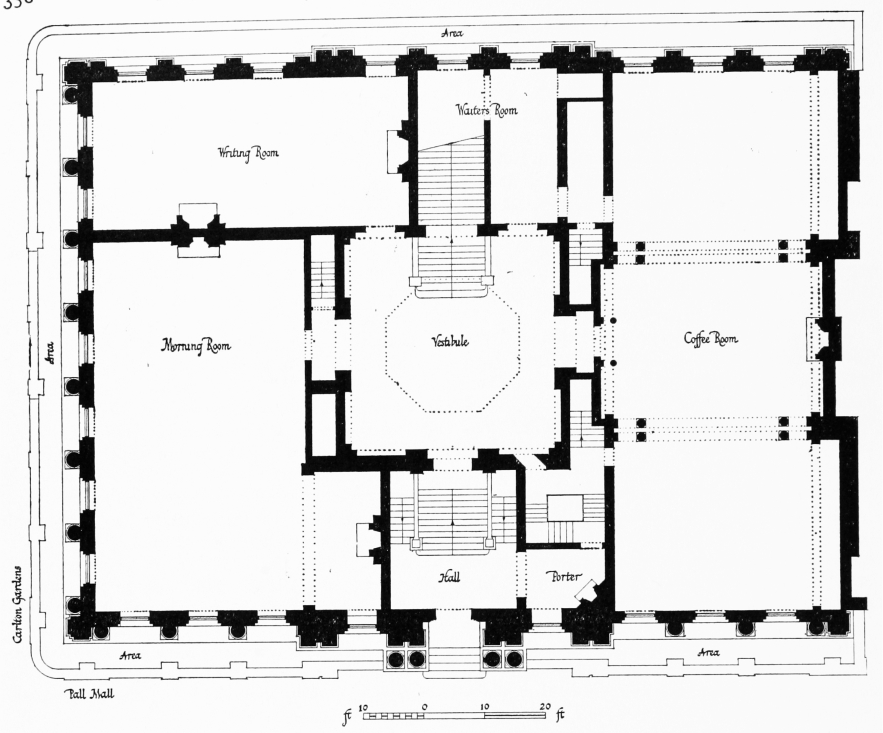

Ground-floor plan of Sydney Smirke’s clubhouse for the Carlton Club, constructed 1854-6 & in use from 1856-1940. The Morning Room on the left-hand side was where Sir Clive Morrison-Bell was located in the eyewitness account quoted at length below; Sir Clive would have been by the window near the top-left corner of the room, staring diagonally across to the fireplace in the bottom-right corner. (Picture credit: F. H. W. Sheppard, Survey of London: Vols 29-30, St James Westminster, Part 1 (London: London County Council, London, 1960), p. 358.)

Air raids on London

The Luftwaffe’s failure to disable the RAF in the Battle of Britain during the summer of 1940 caused them to switch tack. The Luftwaffe’s attention shifted to the civilian bombing campaign known as “The Blitz.” This was to continue with intensity for the next eight months, with occasional bombings and “mini-blitzes” for the remainder of the war. And for the 57 consecutive nights from 7 September to 3 November 1940, Londoners had to cope with nightly bombings.

The remains of the first-floor Smoking Room of the Carlton Club, after the bombing, photographed on 15 October 1940. The Smoking Room was located above the ground-floor Coffee Room. (Photo credit: author’s collection.)

14th October 1940

The evening started like many others that autumn, with the expectation of another bombing raid, and the blackout. The Club had several large dinners booked that night. Dining times had been moved forward half an hour, to allow staff to return home early so as to minimise time spent commuting in the Blitz.

It is often said that half the cabinet were assembled in the Club that night, though it is also possible this figure was exaggerated; for security reasons, press coverage was rather vague on the precise attendees. Assorted memoirs, letters and other sources have identified the names of some dozen politicians present that night, though the only serving cabinet member among them was the Conservative Chief Whip Captain David Margesson, who lived in the Club.

The exterior of the Carlton Club photographed on 15 October 1940, showing fallen masonry littered across the surrounding street - but the walls still standing. Sir Clive Morrison-Bell observed that, “Great blocks were lying about in the street” after the bombing. (Photo credit: author’s collection.)

The fullest eyewitness account of the bombing remains a letter written the next day from former Tory MP Sir Clive Morrison-Bell (still clearly in a state of shock) to the Carlton’s Chairman, the 5th Earl of Clanwilliam, quoted in Petrie and Cooke’s history of the Carlton:

“In a sense I am in a good position to tell the story, for though there were some ten or more Members sitting together talking in the centre of the morning-room, I was musing myself in the far corner of the room to the right of the door as you go in; having just put down the evening-paper, I was sitting there looking for a moment towards the Pall Mall end of the room, and thinking it was about time to go and have some dinner. In what immediately followed I somehow seemed to feel myself a kind of fascinated spectator in the back row of the stalls, taking an objective sort of interest in the unbelievable and amazing goings-on at the far end of the room. I suppose really before the darkness supervened it could only have been a matter of a few seconds, perhaps ten or twelve at the outside, and yet what happened all seemed to me at the time, for some unexplained reason, to be following quite an orderly course. I tried during what proved to be rather a sleepless night to reconstruct what must have more or less taken place.

“It would be just about 8.30 P.M. For some moments a ’plane seemed to have been hovering about somewhere overhead, when suddenly one instinctively realised the final rushing sound of an approaching bomb. Immediately came the most appalling and frightful crash. I will not attempt to describe it, for by now most Members will have a pretty good idea of the deafening noise that a nearby bomb makes; but I think it would take the Prime Minister himself adequately to paint the effect of a high explosive bomb at what might be described as the far end of the room. I heard [Carlton Club Secretary] Colonel [Audley] Willis say next morning that he thought there were two bombs, and I am inclined to agree that he is right in this, for I remember quite distinctly a sort of double sequence. First appeared from near the far fire-place a great triangular wedge of brick, something which might be described as looking like a large slice of brown cake. It appeared, from where I sat, as if it might be the fire-place wall being forced out by the explosion across the room in an easterly direction; then immediately afterwards, in reality I dare not say much more than a split second, another large brown slice came crashing down. This, in a way, seems rather to confirm the theory of a second and almost simultaneous bomb. If, as it appeared likely, it was the fire-place wall coming out into the morning-room, this would immediately let loose the ceiling and with it the library floor, and so on right up to the roof itself. So down this brown avalanche crashed on to what used to be the newspaper table. It was rather like thunder rolling down, and with just at first the slightest break, which might or might not fit in with the second bomb theory. In fact I seemed to have time take in a sort of wave of crashes approaching the cente of the room towards where the little group of Members were sitting. Then something new occurred. Great masses of black smoke came pouring through the swing-doors from the hall across the room, blown no doubt by the explosion but obviously not the explosion itself, for nobody in the direct path, as these ten Members would have been, could have survived.

“One might here pause to ask where did the actual explosion force go? Across the room at the far end I should think, and fortunately not up to it, or surelyby the blast we should all have been blown to smithereens. Besides a lot of it must evidently have been taken up and absorbed by the stoutness of the building itself and the solidity of its walls. My theory, for what it is worth - and an inspection of the building might alter it in many respects - is that the bomb (or bombs) came through somewhere about the corner of the committee room [above the front entrance of the Club], perhaps not far from where the old wireless used to stand; then some of the wall went out, letting down the roof, but with the other wall (that cross wall near the fireplace) holding, so that the force was thus diverted across instead of up the room. It is a chastening thought to reflect that had all this occurred about twenty minutes later, it would almost certainly have found most, if not all, of the Members gathered around the wireless in the Library upstairs to hear the nine o’clock news, and they would thus have been not very far away from the direct path of the bomb.

“But to return to the story; the danger still seemed to be the roof. It was crashing down in tons. What was going to stop the advance? ‘Look out, there’, I instinctively shouted, though in that din could hardly have been heard, and anyhow what could any of them have done? And then came darkness, thick darkness with choking black smoke and a bitter acrid taste that dried up one’s throat.

“All this takes some time to describe, I know, but it could really have been only a matter of a few seconds. And what stopped the roof coming down until the whole thing was on our heads? I really don’t know, but I should have liked to have had a look inside, by daylight, to have seen if there was some structural reason. Anyhow I now found myself wondering - for the objective spectator attitude had faded and in a flash given place to the personal-safety factor - will this roof-crashing reach my corner, and, at the best, bottle me up, where I am sitting? It is an extraordinary circumstance that the roof with its many tons of girders and masonry must have stopped coming down within a few feet of where the Members were sitting; I rather think it was Victor Warrender who was sitting in the circle with his back to the window, and this mass of rubble must have come down within four or five feet of his chair, and anyhow it was only a foot or two more from the others; the high tide probably reached up to that red-leather sofa that faced the Pall Mall windows.

“There now seemed to be a sort of horrified pause of a second or two, and then I suppose we all sprang to our feet. Through the din, I could hear far-away voices - ‘Are you there; is anybody hurt there; here give me your hand; who is this, are you sure there is nobody hurt,’ for it must be remembered that we now seemed to be envelped in inky darkness. Somebody said, ‘Better try and get to the door,’ and it was then that I moved across to join up. In this little groping party I cannot recall all who were there, but I remember the Chief Whip [David Margesson], [William] ‘Shakespeare’ Morrison, Harold Macmillan, [Herwald] Ramsbotham, [Ronald] Cross, Lord Hailsham, and evidently young [Quintin] Hogg, for I could hear the latter saying, ‘It is quite alright, Father, it is quite alright’, and I think Lord Hailsham replying, ‘Yes, I am sure it is.’ There were one or two more whom I could not see in the dark; it might interest you to find out who the others were. I flashed a small torch I happened to have in my pocket, but it was hardly possible to see one’s hand with it, owing to the thick and smelly clouds of black smoke.

“But after all, was it, as Lord Hailsham said, alright? How much more roof was coming down? What kept it up now? Was there still a floor to cross on, or had that gone too? And so slowly towards the door, and out into the hall, the little party moved, now all close together. What about that gallery [the balcony on the first floor, over the central hall]? Has it come down, or is it going to? What about the stairs, are they still there? The feeble light hardly showed anything, but the stairs were as a matter of fact still there, even if the ballustrade had gone, and slowly the little group felt its way down towards the front door. Somebody said, ‘Where is [Club Secretary Colonel] Willis? Can we do anything to help him?’ And another voice, ‘He has probably gone down below to find out about his staff.’ At the foot of the stairs a large heavy door was on the floor, and had to be picked up and laid on one side before the street was finally reached, where the first thing to be seen were around twenty incendiary bombs spluttering away all round. I saw somebody, I think it was the Hall Porter, go up and kick one; it barked at him, and exploded, and he kicked it again and shortly got it out. Apparently, a Molotov breadbasket had been released with the bombs. The appalling extent of the damage could only be fully realised the next morning, when great blocks were lying about in the street, some of which must have weighed about a ton. In fact I was moving that night along the pavement, or rather climbing over the debris, I suddenly heard a heavy thud just a few feet behind me, in fact unpleasantly close. It must have been a dilatory block that had decided to come down, and the following morning I noticed a lump there about the size of a small suit-case that from its position fitted in with my particular thud.

“Looking back, perhaps the most wonderful thing about it all was that everybody, both the Members and the Staff, seems to have got away from that inferno without a scratch; strange, nay providential, when it can with truth be said that death itself was stalking through the Club.”

Harold Macmillan confirmed in his memoirs that two main bombs had hit the Club, the first in the morning room, but lodged in the ceiling:

“A bomb had struck the cornice in the far end of the room. Had it come straight through we should no doubt not have escaped. Groping our way out towards the hall, we found some members coming out of the dining-room [the ‘coffee room’ on the above floorplan], where another bomb had fallen.”

Henry “Chips” Channon wrote in his diary later that night that he was sitting down to dinner when Harold Balfour turned up on his doorstep at 5 Belgrave Square, covered in black soot. Balfour had been at the Carlton with Margesson, Warrender and Ramsbotham:

“drinking sherry before going to dinner. With a flash, the ceiling had fallen and the club had collapsed on them. It was a direct hit. Harold swam, as he put it, through the rubble, surprised to be alive. He soon realised that his limbs were all intact and he called out to his companions who all answered, so we know them to be safe. Somehow he got to the front door and found it jammed. At that moment he saw Lord Hailsham being half led, half carried out by his son, Quintin Hogg. A few other individuals, led by Harold, rammed the door and it crashed onto the street. By then a fire had started. Harold remembered that he had left his car, an Air Force one, nearby. He went to it and found only a battered heap of tin, but the chauffeur, an RAF man, was luckily untouched as he had gone into the building…Harold came here for a bath, champagne, and succour, and we gave him all those things.”

The Carlton Club later in October 1940, photographed from the roof of the Junior Carlton Club across Pall Mall, giving a clear view of the Carlton’s collapsed roof and interior of the building. The areas of roof collapse seem consistent with Sir Clive Morrison-Bell’s hypothesis that the bomb(s) fell into the first-floor Committee Room, over the front entrance, exploding sideways. (Photo credit: Sir Charles Petrie and Alistair Cooke [Lord Lexden], The Carlton Club, 1832-2007 (London: Carlton Club, 1955, rev. 2007).)

Other clubs impacted

The Carlton was not the only club damaged that night.

Its neighbour to the west, the RAC, had several small blazes of its own from incendiary bombs which needed to be put out by its staff firefighting teams, before they turned their attention to stopping the fire from the Carlton spreading. 25 staff were injured, mainly from glass splinters, and numerous RAC bedrooms were rendered unusable.

The Reform Club, to the east, was also damaged by incendiary bombs that night. The next club east, the Travellers, suffered serious damage from incendiary bombs and high explosive bombs, including the collapse of the ceiling over its coffee room. Incendiary bombs on the rear side destroyed the roof, and gutted two floors of bedrooms. Meanwhile, both the Travellers and its eastern neighbour the Athenæum each had their windows facing Pall Mall shattered. The United Service Club and the Union Club, both looking onto Waterloo Place, also suffered damage that night.

The incendiary bombs which fell on the Carlton alongside the one or two main bombs caused serious complication throughout the night. Although the RAC successfully managed to stop the flames from encroaching further west, fire nonetheless spread south, to the rear of the Carlton building, running down Carlton Gardens. The result was the gutting out of the Carlton’s ladies’ annexe at 7 Carlton Gardens.

Across the road from the annexe, at 1 Carlton House Terrace, the Savage Club had also been hit by a bomb, around 3:45am on the 15th October.

Each of the other clubs would recover - but the Carlton’s Pall Mall clubhouse and its ladies’ annexe would never do so.

Aftermath

Harold Macmillan observed:

“Although there must have been over a hundred members and servants in the club, there were no casualties from the attack itself, although one man was killed by a piece of falling masonry on his way out.”

This seems consistent with a source at the Reform Club that night, who reported that there were 38 members in the Carlton, plus an indeterminate number of staff. (A staff of several dozen would have been normal at the time.)

Macmillan described the rest of his evening:

“Margesson and I went to look for his car, but that had been destroyed. We then thought it was time for dinner ; so we crossed the road to the old Carlton Hotel…where we thought we could comfort ourselves with food and drink. We were received in a very doubtful, not to say suspicious, manner by the maitre d’hotel, who in normal times was well known to us both. When we looked in one of the looking-glasses we could see the reason. Our hair, faces, and clothes were completely blackened with dirt and smoke. We gratefully accepted the offer of a bathroom. By that time it was getting pretty late, so I made my way to Pratt’s…where I found my brother-in-law, Eddy [10th Duke of] Devonshire. While we were sitting there, someone came in to say that his house, No. 2 Carlton Gardens, was on fire. We thought we had better go along there. The fire was gradually got under control, and later we were able to go in and carry out some bits of furniture and other effects.”

The Carlton Hotel itself was heavily damaged in a bombing six weeks later, on 28 November 1940, ceasing to trade as a result of the harm caused. The remaining parts of the building were seized by the British government in 1942 for use as office space, before the whole building was demolished in 1957-8, to be replaced in 1963 by the Grade II-Listed brutalist New Zealand House.

The Carlton Hotel, on the corner of Pall Mall and Haymarket, to which members of the Carlton Club repaired for dinner, immediately after the bombing. The building has since been demolished, although the adjoining Her Majesty’s Theatre (on the right), built in the same style, still stands. (Photo credit: 'Plate 36: Carlton Hotel and Her Majesty's Theatre, Haymarket', in F. H. W. Sheppard (ed.), Survey of London: Volumes 29 and 30, St James’s, Westminster, Part 1 (London: HMSO, 1960).)

Winston Churchill paid a visit to the bombsite of the Carlton Club the next day, observing that the lack of death toll in the bombing had been a minor miracle. He later repeated these comments in Cabinet, with one of his Labour colleagues quipping, “The devil looks after his own.”

Because of the wartime news blackout, the bombing of the Carlton was not reported in the press until nearly a month later, on 11 November 1940.

In the meantime, the Carlton’s members set about getting their bearings. The displaced Carlton members were offered hospitality by the Reform Club next door - a display of cross-party solidarity, given the traditional acrimony between the two clubs set up for rival political parties. The Travellers Club also extended hospitality to the Carlton’s members. Such arrangements could not be expected to continue indefinitely, though: with wartime shortages, clubs often jealously guarded their stockpiles of comforts such as port.

The ruins of the Carlton Club photographed nearly a month after the bombing, on 11 November 1940 - by this time, some of the surrounding fallen masonry has been cleared, but the full hollowness of the building can be better seen. (Photo credit: WHNT.com.)

The Carlton searched for an alternative building of its own. By coincidence, a nearby club — Arthur’s — had only recently closed down, in February 1940. Arthur’s had been founded in 1811 as an aristocratic gambling club, and since 1827 it had occupied a purpose-built clubhouse at 69 St. James’s Street, atop a site occupied by White’s from 1698-1733, and again from 1736-1778. There were some concerns among Carlton members about moving from such a large Victorian clubhouse to a more intimate set of Georgian premises, but these were brushed aside, not least as 69 St. James’s Street was seen at the time as simply being a temporary stopgap. After numerous technicalities around the lease were resolved, the Carlton Club moved into St. James’s Street in 1943.

This view from later in the war, with the Carlton and the RAC highlighted, shows that part of the front façade had by this time collapsed. (Photo credit: author’s collection.)

The former Carlton Club site on Pall Mall

The Carlton Club bombsite on Pall Mall was to remain derelict for 15 years, with the gradual disintegration of the external walls. Eyebrows may be raised today at the thought of prime real estate on Pall Mall languishing for so long, but this was not unusual in London during the post-war years: the devastating scale of the bomb damage, the competition between different building priorities, and the serious financial problems Britain faced, all meant that it remained fairly common until the 1960s for large wartime bombsites in prime central locations to remain undeveloped.

The Carlton Club bombsite (right) seen over 15 years on from the bombing, in this screenshot from The Man Who Never Was (1956). By this stage, the front and side walls have either been removed, or collapsed, while the rear wall still stands. London had many such open bombsites still remaining in the 1950s.

Meanwhile, in the post-war years, the Carlton developed plans to rebuild its previous clubhouse on its original site - no mean feat, given the craftsmanship and Victorian building techniques that would have been involved, to say nothing of the dilemmas posed by reconstructing a building whose design had evolved considerably over a century. Winston Churchill in his capacity as Conservative Party leader fronted a financial appeal to members, seeking to raise the funds for this ambitious scheme.

Yet sufficient amounts were never raised, and the plan ended up being kicked into the long grass. Furthermore, the Carlton faced exactly the same financial pressures in the post-war years which led to the closure of so many other clubs, including falling revenues, high inflation, and a demographic time-bomb with older generations of members rapidly dying out. By the early 1950s, the Carlton needed money, and it needed it fast.

It therefore agreed in 1955 to the sale of its lease on the Pall Mall plot to Rudolph Palumbo, one of whose specialisms was the redevelopment of former bombsites. Palumbo redeveloped it into a neo-classical office block designed by Donald McMorran with Duke & Simpson, which was built on the site in 1956-9. It can still be seen today, numbered 100 Pall Mall. (As a Grade II-Listed building, details of its Listing can be found here.)

Abandoning the planned Pall Mall rebuild project also enabled the Carlton Club to raise the funds for much-needed sustenance to take it through a difficult financial patch. It was at this point, after over a decade of occupancy, that the ‘temporary’ premises at 69 St. James’s Street were deemed to be the Club’s permanent home.

The office building numbered 100 Pall Mall, which stands on the site of the old Carlton Club building at 94 Pall Mall, was built in 1959. To the left is the Reform Club, and to the right, the Royal Automobile Club. (Photo credit: LoopNet.)

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.