William Hogarth’s “A Rake’s Progress” (paintings 1732-4; engravings 1734-5) is a seminal piece of social satire. Across its eight panels, it tells the tale of an idle and dissolute young man who comes to London and fritters away his fortune on loose living, and ends up in debtor’s prison, and then bedlam.

Two of the eight panels depict White’s club in its earliest incarnation - one shows us the exterior, the other the interior. They tell us much about how White’s was seen in its earliest incarnation, as an informal gambling club behind White’s hot chocolate shop. They are also a visual indicator of the 1733 fire and its aftermath, which was to play a key part in the evolution of White’s into a fully-fledged club.

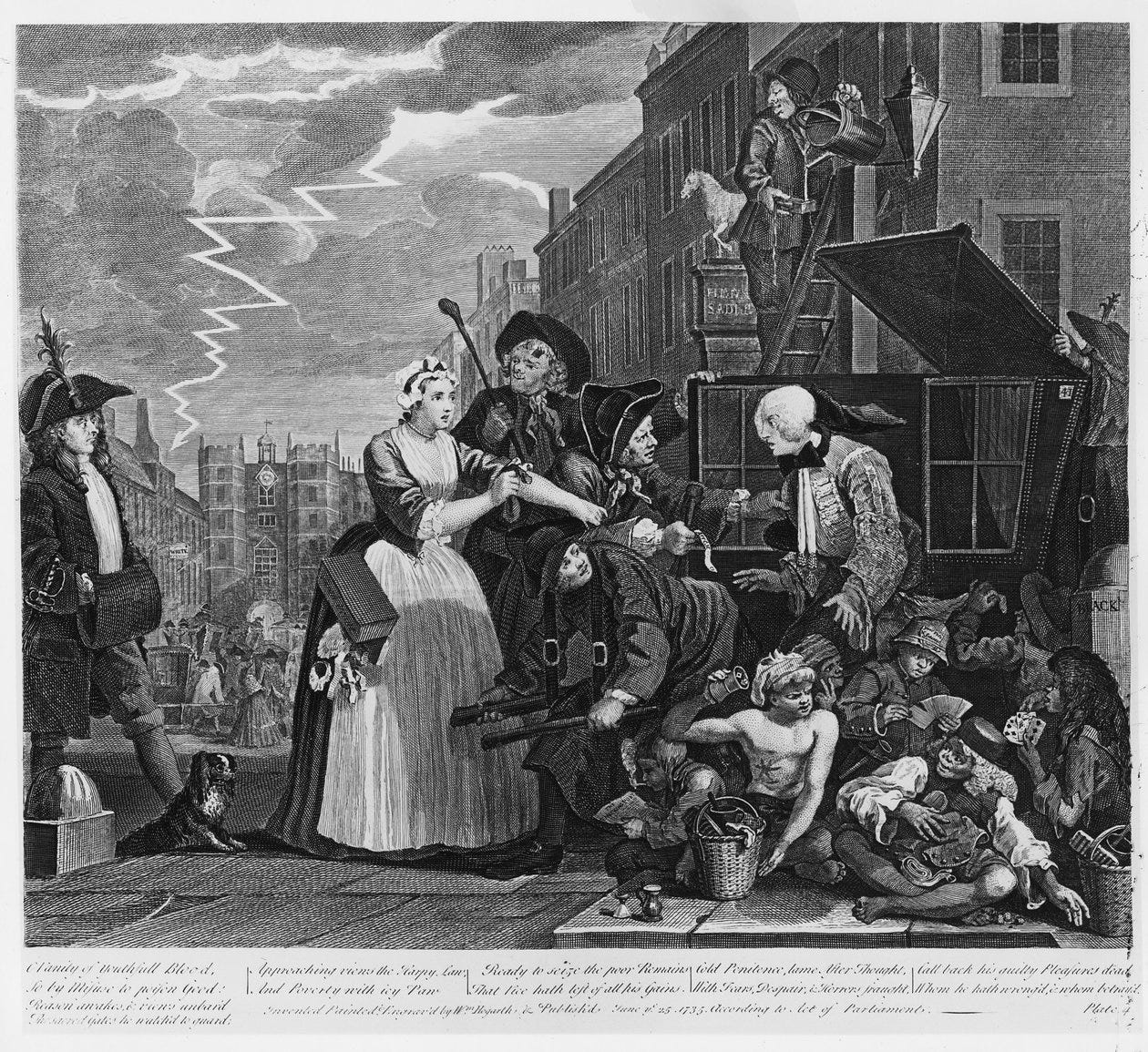

Panel IV: The Arrest

In this panel, White’s is merely part of the background - though is much more prominent in the engraved version than in the original painting. We see the young rake in a sedan chair attempting to attend a Queen Caroline’s St. David’s Day birthday at St. James’s Palace, seen in the distance at the foot of St. James’s Street, while he is being accosted by a bailiff. Only the kindly financial intervention of the former fiancée he spurned in the very first panel saves him from the bailiff. A lamp man refilling the lantern in the background spills oil over the rake - a literal rendering of the old observation that blessings are accompanied by oil over the head.

The Arrest: original painting. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

The engraving version of Panel IV is where things begin to get more interesting. (Hogarth’s engravings were always rendered as flipped versions of the original painting compositions, since Hogarth would etch his interpretation of the painting onto a copper plate, which would reverse the image whenever a paper copy was pressed.)

Certain extra details are found in the engraving version. One is the addition of a clear label, marking White’s club at its then location, further down St James’s Street. Another is the addition of a thunderbolt - an allusion to the catastrophic fire which burned down the Club’s premises.

The Arrest: engraving version. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

The fire which burned down White’s on 28th April 1733 is well-documented. Since the death of Francesca, “the widow White” in 1729, both White’s chooclate shop and the White’s club around the back of the building had been run by John Arthur, who had been a faithful servant of both Mr. and Mrs. White since 1701. He was assisted by his son, Robert Arthur. Arthur Sr. was to see much of his life’s work go up in flames. According to the Daily Courant on 30th April 1733:

“On Saturday morning [at] about four o’clock a fire broke out at Mr. Arthur’s, at White’s Chocolate House, in St. James’s Street, which burnt with great violence, and in a short time entirely consumed that house, with two others, and much damaged several others adjoining. Young Mr. Arthur’s wife leaped out of a window two pairs of stairs upon a feather bed without much hurt. A fine collection of paintings belonging to Sir Andrew Fountaine, valued at £3,000 at the least, was entirely destroyed. His Majesty [King George II] and the Prince of Wales were present above an hour, and encouraged the Firemen and People to work at the Engins - a guard being ordered for St. James’s to keep off the populace. His Majesty orderd 20 guineas among the Firemen and others that worked at the Engines and 5 guineas to the Guard; and the Prince ordered the Firemen 10 guineas.”

Although Arthur was insured for up to £400 in damages, he lost over £200 in plate and £100 in cash in the fire.

A newspaper advertisement taken out by John Arthur on 3rd May 1733 in the Daily Post informed readers that after the fire, White’s had:

“removed to Gaunt’s Coffee House, next to the St. James’s Coffee House in St. James’s Street, where he humbly begs that all will favour him with their company as usual.”

Close-up on the engraving version of The Arrest, showing how clearly labelled White’s is in this version, with the thunderbolt.

For the next three years, White’s was to be based at Gaunt’s Coffee House, at the foot of the street near St. James’s Palace, while the former premises were rebuilt on their old site. This is confirmed by the Rate Books for the street, which show Arthur occupying the Gaunt’s building.

When Hogarth came to depict ‘A Rake’s Progress’, these would all have been very recent events, with the rebuilding of that whole side of St. James’s Street being an ongoing occurence over the next three years.

Algernon Bourke, the first historian of White’s, deduced “It would seem that Hogarth had painted this picture before the occurence of the fire at White’s in 1733”, and that “Hogarth made great alterations” to Panel IV between the oil painting version from 1732-3, and the etching from 1734-5, including the addition of a troop of boys in the foreground, and the addition of White’s in the background.

The Arrest: the watercoloured version of the engraving, in the possession of White’s today. (Picture credit: Anthony Lejeune, White’s: The First Three Hundred Years (London: A & C Black, 1993).)

The White’s seen at the foot of St. James’s Street in the etching is therefore not the burned-down building of 1733, but the temporary lodgings it had undertaken at Gaunt’s Coffee House - though the thunderbolt seen coming from the heavens in the etching version might also be interpreted as a symbol of divine intervention; a satirical device.

Bourke deduced that Hogarth had coincidentally included the Gaunt’s building as a backdrop in his earlier painting, and decided to emphasise it more prominently by the time he came to the etching version.

A rare reversed version of Panel IV, which copies the print to flip the image over back to the correct way, matching the original orientation of the painting - and restoring White’s to the correct side of the street, as held in the British Library collections. Algernon Bourke, The History of White’s, with the Betting Book from 1743 to 1878 and a List of Members from 1736 to 1892, vol. 1 (London: privately published, 1892), plate facing p. 19.

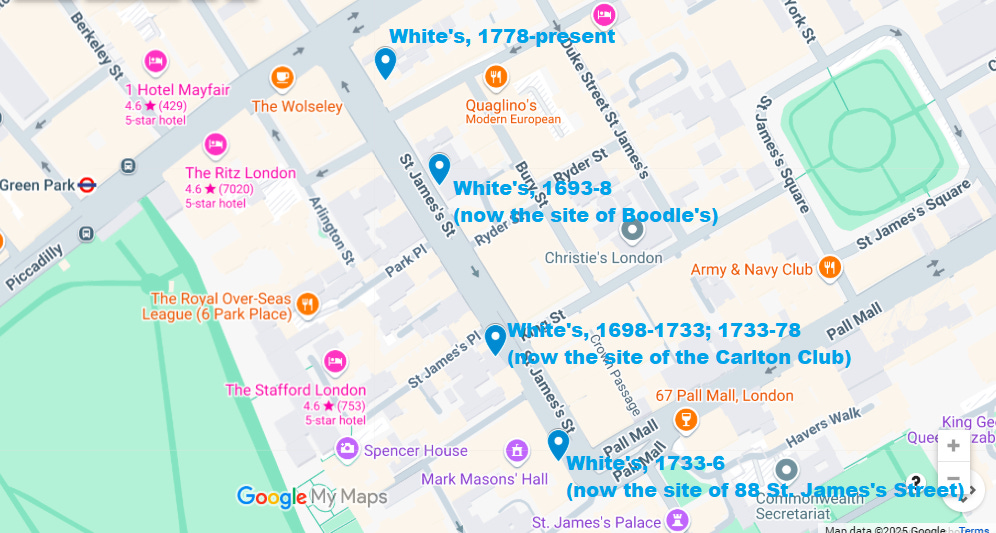

Of course, one consequence of flipping the image over in its conversion from a painting to an engraving is in putting White’s on the wrong side of the street for the engraving version - something which has caused confusion among historians over the years. This is best clarified with reference to the map below. From 1698 to 1733, White’s occupied a site roughly where the Carlton Club exists today at 69 St. James’s Street.

The sites of White’s, superimposed over a modern map of St. James’s Street. (Base map: Google Maps.)

The rebuilding of White’s in 1733-6 proved to be highly consequential. Until the fire of 1733, the focus of the business permises had been on its legitimate front-end, as a fashionable hot chocolate shop, with the gambling in the back room being something of a lucrative sideline. Yet the reconstruction of 1733-6 afforded the opportunity to build a dedicated clubhouse, without any attached chocolate shop. A new set of rules was drawn up in 1736, marking the transition to being a club. John Arthur did not live to see the opening of the new premises, but his son Robert Arthur presided over their opening. Hogarth’s picture therefore captures this final state of transition.

Panel VI: The Gaming House

The Gaming House: original painting. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

Panel VI of Hogarth’s ‘A Rake’s Progress’ captures the rake well on the path to moral and financial ruin. Long reputed to depict the interior of White’s, it shows the rake having lost yet another fortune at the gaming tables - this one having been acquired by a marriage of convenience to an elderly widow in the previous panel. The rake screams up to the heavens for mercy, while surrounded by drunken and indebted gamblers.

Meanwhile, in the background, the members notice that the building is on fire, and they attempt to put out the flames in vain - a detail that is rendered much more clearly in the subsequent etching version below, though is still very much already present in the painting version.

There is some ambiguity as to whether the version of White’s depicted is the one that burned down, or a moral warning that the same thing might happen to the Club in its new premises at Gaunt’s coffee house. It is quite possible that it was a synthesis, with elements of both, and a fair degree of creative licence.

The Gaming House: engraving version. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

Conclusion

Hogarth’s portrayal of White’s in its early years is far from flattering: an idle, dissolute, drunken, low gambling den which is quite literally damned with a thunderbolt from the heavens. Yet this seminal piece of social satire is also an important visual record of a key moment in the evolution of London’s first club, just as it was transitioning from being a hot chocolate shop to a club, in the aftermath of the fire of 1733.

Further reading

Algernon Bourke, The History of White’s, with the Betting Book from 1743 to 1878 and a List of Members from 1736 to 1892, 2 vols (London: privately published, 1892).

Anthony Lejeune, White’s: The First Three Hundred Years (London: A&C Black, 1993).

John Bowyer Nichols (ed.), Anecdotes of William Hogarth, Written by Himself (London: privately published, 1833)

Jenny Uglow, Hogarth: A Life and a World (London: Faber & Faber, 1997).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.