This piece first appeared in the Sherlock Holmes Journal (34:3), Winter 2019, pp. 110-117, drawing on material I had first shared in a talk to the Sherlock Holmes Society of London for their Annual General Meeting on 14th March 2019. It is a follow-up to my earlier piece identifying the fictional Diogenes Club in the Sherlock Holmes stories.

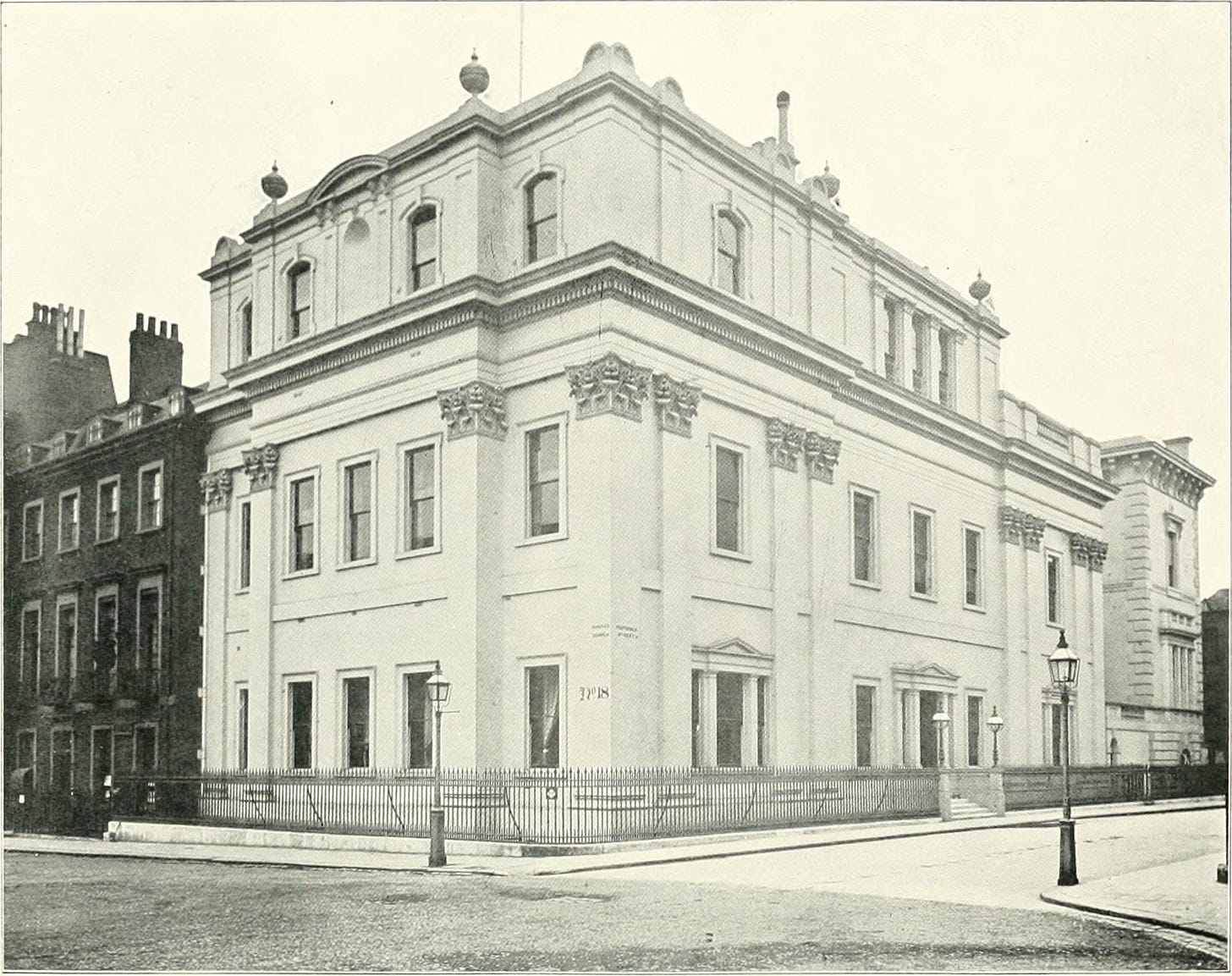

The Oriental Club on Hanover Square from 1826 to 1962 - the most likely candidate for Doctor Watson’s Club.

Considerable effort has been expended over the years in correctly identifying Mycroft Holmes's club, the Diogenes.[i] Yet clubs can be found throughout the canon, in 13 of its 60 stories.[ii] By the 1890s, when London contained some 400 West End clubs, to say nothing of the thousands of working men's clubs which peppered the country, clubs were an established facet of British life.

It is therefore unsurprising that Dr. Watson should have had a club of his own – yet doubly surprising, given the rich vein of Sherlockian scholarship, that so little effort has gone into correctly identifying it.

Admittedly, the clues offered are rather slender. Watson's club merited two mentions in the canon. Firstly, in 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', Watson briefly alluded to having “spent all day at my club and did not return to Baker Street until evening.”[iii] Secondly, in 'The Dancing Men', Watson returned from a billiards game at his club, where he had considered – and dismissed – an investment proposal from a fellow member.[iv]

Leslie S. Klinger has speculated that Watson might have been a member of London's most prestigious military establishment, the United Service Club, basing this deduction on the Club's number of infirm members, but this seems highly unlikely.[v] The Club's large number of infirm members was not due to any particular propensity in its admissions policy – as Klinger incorrectly deduces from its “Cripplegate” moniker – but was simply a by-product of the exceptionally large number of elderly members the Club contained, having been founded for senior army and naval officers of the ranks of Major and Commander and above (ergo the Club being popularly known as “The Senior”).[vi] Whilst a relaxation of the rules came into effect in 1894, permitting army Captains to join as well, this date cannot be reconciled with the 1888 date provided by William S. Baring-Gould for the events of 'The Hound of the Baskervilles'.[vii] There is no indication in the canon of Watson having ever been a senior officer – and there are a fair few indications, including his lowly status as “Assistant Surgeon”, and his modest means in only affording shared rooms on his army pension, that he was a mere subaltern, most likely a 2nd Lieutenant.[viii] (Watson wryly noted that the Afghan campaign brought “honours and promotion to many, but for me it had nothing but misfortune and disaster”, suggesting that no promotion came his way before his medical discharge.) So the United Service Club would have been a closed world to him.

How, then, are we to extrapolate Watson's club, with so few clues available?

The Drawing Room of the old Oriental Club building on Hanover Square.

The most popular clubs of Victorian London were the purely social clubs, which did not have any theme, but simply existed to promote conviviality.[ix] (These were also the first clubs to close down in the twentieth century, making their success short-lived.) Yet Watson was unlikely to have been a member of a social club. Quite apart from cutting a solitary figure in the canon, with few named male friends aside from the remarkably antisocial Sherlock Holmes, consider the following exchange from 'The Hound of the Baskervilles':

“You have been at your club all day, I perceive.”

“My dear Holmes!”

“Am I right?”

“Certainly, but how?”

He laughed at my bewildered expression.

“There is a delightful freshness about you, Watson, which makes it a pleasure to exercise any small powers which I possess at your expense. A gentleman goes forth on a showery and miry day. He returns immaculate in the evening with the gloss still on his hat and his boots. He has been a fixture therefore all day. He is not a man with intimate friends. Where, then, could he have been? Is it not obvious?”[x]

Similarly, in 'The Dancing Men', Holmes observed that when Watson was in his club, “You never play billiards except with Thurston.”[xi] Clearly, Watson's club was far from being a hive of social activity.

The second most common type of London club in the nineteenth century (and “by far the largest category after 1880”) was the political club.[xii] It is unlikely that Watson belonged to one of these, either. There is conspicuously little mention of politics in the canon, much less of Watson's own politics.[xiii]

This leaves the next most common type of London club, which was based around shared interests.[xiv] We can immediately discount several large subcategories of these. With 'A Study in Scarlet' having received its first publication to a rather muted reception in 1887, yet Watson already being an established fixture in his club by the 1888 events of 'The Hound of the Baskervilles', we can immediately dismiss the clubs with large literary memberships, such as the Athenaeum or the Savile Club. At that stage, he would have been simply too obscure an author to have been elected. It is also unlikely that Watson would have had any obvious grounds for membership of clubs in the arts, such as the Arts Club, or the Garrick. Nor would his war wound have lent itself to active membership of a sporting club, such as the Badminton, Boxing or Hurlingham Clubs. Nor would Watson have seemed a natural 'fit' for any of the clubs themed around educational background – while we know that he was a University of London man, it was not a university which had its own affiliated clubs; and indeed, University of London alumni were specifically barred from the various university clubs. And he would have been unlikely to have joined any of London's clubs for expatriates of other nations, such as the Argentine Club, the Scandinavian Club, or Den Norske Klub. This leaves a major category of clubs that he would have been well-qualified for: the military clubs. But which one?

A clue to the whereabouts of Watson's club is offered by his complete unfamiliarity with the Diogenes Club on Pall Mall.[xv] It is therefore unlikely that Watson spent much time walking around that thoroughfare, with its high concentration of clubs. We can therefore immediately discount the Army and Navy Club at 36-39 Pall Mall, which directly faced my own nomination for the Diogenes Club, the Junior Carlton Club.[xvi] (The United Service Club also fails on this count, having been located at 116-119 Pall Mall.)

Similarly, if we accept that the Diogenes Club was indeed the Junior Carlton – and as I have argued elsewhere, the Junior Carlton is the only club for which all of the evidence fits – then we can also disregard several other nearby clubs from having been Watson's club.[xvii] The East India United Service Club, as it then was, at 16 St. James's Square, overlooked the back of the Junior Carlton Club building, which monopolised the south side of the square – it is unlikely that Watson could have failed to notice the Junior Carlton if entering and leaving the East India with any regularity. Nor was Watson's club likely, for the same reason, to have been on any nearby street to Pall Mall, such as the Junior United Service Club on Charles Street (which unlike its 'Senior' namesake, did admit junior officers), nor the Junior Army and Navy Club which was positioned at 10 St. James's Street from 1882 until 1904.[xviii]

We can also disregard two other military clubs – the Cavalry Club at 127 Piccadilly, and the Guards' Club at 70 Pall Mall – as Watson, formerly of the 5th Northumberland Fusiliers and the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot, would not have been entitled to join. (It is also worth pointing out that the Cavalry Club was not founded until 1890 – early enough for the 1898 events of 'The Dancing Men', but too late for the 1888 events of 'The Hound of the Baskervilles'.)

This leaves us with three military clubs which Watson could have belonged to, that were housed at the following addresses, during the period covered by the canon:

Naval and Military Club, Cambridge House, 94-96 Piccadilly

Junior Naval and Military Club, 97-99 Piccadilly

Oriental Club, 18 Hanover Square

Of these, I would plump for the Oriental Club, for two reasons. Neither reason constitutes definite proof (and convincing cases can still be made for the Naval and Military Club, and the Junior Naval and Military Club next door). Nevertheless, these reasons make the Oriental Club the clear favourite.

Firstly, when selecting a military club, it is likely that Watson would have plumped for one to which he had an obvious connection. While much is made of his service in Afghanistan, it should not be overlooked that he “was stationed in India”, after “landing at Bombay” – by far the most common route for British troops to reach Afghanistan at the time.[xix] It therefore seems likely that Watson would have been most at home in one of the Indian-themed military clubs, of which there were two. The first, the East India United Service Club, has already been discounted above. That leaves the Oriental Club, which welcomed members from across “the East” – not just India.

Secondly, it is likely that Watson's club would have been easily accessible to him. It is debatable, in a “chicken and egg” manner, whether Watson's Baker Street accommodation would have influenced him to seek out a nearby club, or whether Watson had an existing club which would have influenced him to seek out nearby accommodation. We do not know when he joined his club, except that it was prior to 1888. He may well have joined around 1881, fresh on his return from Afghanistan, and around the time of taking up the rooms on Baker Street, which he considered “desirable in every way.” But we should note the location of the Oriental Club from 1826 to 1962 – far further north than most other London clubs – was at 18 Hanover Square, a mere 15-minute walk (or 7-minute hansom cab ride) from Baker Street. Watson would have been far better-served by a club located here, than something further south in Piccadilly or Pall Mall, which would have been a 45 minute walk from Baker Street.

Indeed, Watson's evident unfamiliarity with the St. James's district was highlighted by Baring-Gould, who described Holmes and Watson's chosen approach to the Diogenes Club on Pall Mall in 'The Greek Interpreter' as “extraordinary” – they first walked south-east to get to “Regent Circus” (which Baring-Gould and Klinger remind us is an archaic name for Piccadilly Circus)[xx], north of the eastern end of Pall Mall. From there, they then walked west to get to the top of St. James's Street, then walked south down St. James's Street, then walked east along Pall Mall, forming a broad 'C' shape. Along the way, they would have passed countless smaller streets that would have been viable shortcuts. How to make sense of such illogical perambulations? It is evidently a part of town that Watson was unfamiliar with, since his own club lay well to the north, and he seldom had business in the St. James's district, therefore he needed to navigate from familiar features, which did not take him through the most direct route.

The Oriental Club would have suited Watson well. It occupied a modest but stately 1820s clubhouse on the corner of Hanover Square and Tenterton Street, with high ceilings, and a few well-appointed rooms – now sadly long since demolished.[xxi] Its status as a focal point for men in London who had spent time in “the East” would have ensured that Watson could spend his spare time in like-minded company. While it is not absolutely certain, it seems highly likely that Dr. Watson was a member of the Oriental Club.

The main staircase of the old Oriental Club building on Hanover Square.

[i] Charles O. Merriman, ‘In Clubland’, Sherlock Holmes Journal, 7:1 (Winter, 1964), pp. 29-30; William S. Baring-Gould (ed.), The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. I, (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967), p. 591; S. Tupper Bigelow ‘Identifying the Diogenes Club: An Armchair Exercise’, Baker Street Journal, 18:2 (June, 1968), pp. 67-73; Leslie S. Klinger (ed.), The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Vol. I (New York: Norton, 2004), pp. 640-641; David L. Leal, ‘What was the Diogenes Club?’, Baker Street Journal, 67:2 (Summer, 2017), pp. 16-26; David Marcum, ‘Pall Mall: Locating the Diogenes Club’, Baker Street Journal, 67:2 (Summer, 2017), pp. 27-33; Seth Alexander Thévoz, ‘The Diogenes Club: The Case for the Junior Carlton’, Baker Street Journal, 69:3 (Autumn, 2019), pp. 6-24.

[ii] The clubs featured in the canon are the unnamed club of Thaddeus Sholto in 'The Sign of the Four' (1890); the Tankerville Club scandal referenced in 'The Five Orange Pips' (1891); Arthur Holder's unnamed aristocratic gambling club in 'The Beryl Coronet' (1892), where he racked up huge debts betting on cards and the turf (it was most likely based on either the Portland Club and/or the Turf Club); Fitzroy Simpson's unnamed sporting club where he did “a little quiet and genteel book-making” prior to the events of 'Silver Blaze' (1892); the Diogenes Club which featured in both 'The Greek Interpreter' (1893) and 'The Bruce-Partington Plans' (1908); meanwhile, 'The Empty House' (1903) featured two avowed clubmen, the Honourable Ronald Adair, who belonged to the Baldwin, the Cavendish, and the Bagatelle Card Club, and the unscrupulous Colonel Sebastian Moran, who made a living cheating at cards at the Anglo-Indian Club, the aforementioned Tankerville Club, and the same Bagatelle Card Club to which Ronald Adair belonged; Holmes exposed “the atrocious conduct of Colonel Upwood in connection with the famous card scandal” at the Nonpareil Club after the events of 'The Hound of the Baskervilles' (1902), which seems to have been a thinly-veiled allusion to the Tranby Croft card scandal; the Carlton Club served as a navigation point in 'The Greek Interpreter' (1893), and also served as an address for Sir James Damery in 'The Illustrious Client' (1924); Langdale Pike's unnamed St. James's Street club with a bow window was mentioned in 'The Three Gables' (1926), which could have been White's, Boodle's, the Conservative Club, or the New Oxford & Cambridge Club; and of course, Watson's own unnamed club was mentioned in both 'The Hound of the Baskervilles' (1902) and 'The Dancing Men' (1903).

[iii] 'The Hound of the Baskervilles' (1902).

[iv] 'The Dancing Men' (1903).

[v] Leslie S. Klinger (ed.), The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes: Volume II (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), p. 865.

[vi] Klinger bases his deduction on the Club's entry in Ralph Nevill, London Clubs: Their History and Treasures (London: Chatto & Windus, 1911) – a source which is itself laced with errors, some of which Klinger then repeats, i.e. giving a foundation date of 1831 rather than 1815.

[vii] Louis C. Jackson, History of the United Service Club (London: United Service Club, 1937), p. 101.

[viii] ‘A Study in Scarlet’ (1887).

[ix] Antonia Taddei, 'London Clubs in the Late Nineteenth Century' (Oxford: University of Oxford Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History No. 28), p. 8.

[x] 'The Hound of the Baskervilles' (1902).

[xi] 'The Dancing Men' (1903). Meanwhile, Klinger, New Annotated: Vol. II (2005), p. 866 speculates whether the club may be Thurston's rather than Watson's, but this seems improbable – in the 1890s, club billiard-rooms were still a members-only preserve. The only way they could have played billiards together in a club would have been as fellow members.

[xii] Taddei, 'London Clubs', pp. 4, 9-13, 18-24.

[xiii] David L. Leal, ‘What was the Diogenes Club?’, Baker Street Journal, 67:2 (Summer, 2017), pp. 16-26.

[xiv] Antonia Taddei 'London Clubs', p. 13.

[xv] 'The Greek Interpreter' (1893).

[xvi] Seth Alexander Thévoz, ‘The Diogenes Club: The Case for the Junior Carlton’, Baker Street Journal, 69:3 (Autumn, 2019), pp. 6-24.

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] R. H. Firth, The Junior: A History of the Junior United Service Club, from its Formation in 1827 to 1929 (London: Junior United Service Club, 1929), pp. 20-23.

[xix] 'A Study in Scarlet' (1887).

[xx] William S. Baring-Gould (ed.), The Annotated Sherlock Holmes: Volume I (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1967), pp. 592-3; Leslie S. Klinger (ed.), The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes: Volume I (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), p. 639.

[xxi] Alexander F. Baillie, The Oriental Club and Hanover Square (London: Longmans, 1901); Denys Forrest, The Oriental: Life Story of a West End Club (London: B. T. Batsford, 1968); Hugh Riches, A History of the Oriental Club (London: Oriental Club, 1998), pp. 13-15.