47 Parliament Street today, seen from Whitehall - originally built as the home of the Whitehall Club, which it housed from 1866 until 1906. The Red Lion pub can be seen on the left.

My first graduate job involved working in a former clubhouse. Eighteen years ago, I was a lowly parliamentary researcher in the House of Commons. The parliamentary estate today sprawls well beyond Charles Barry's vast gothic building, taking in a network of adjoining buildings, many of them interconnected by underground tunnels beneath Westminster and Whitehall. And one of them, I remember being told on my first day, was a “former gentlemen's club.” Quite literally club government.

Today, 47 Parliament Street stands opposite the Red Lion pub, subsumed into the parliamrentary estate as a research library. Although not open to the general public, the wood-panelled library and ornate plaster ceilings stand testament to its former function, as a purpose-built clubhouse. It has been a Grade II* Listed building since 1970, so many of its architectural features are preserved. But from 1864 to 1866, it was constructed as a purpose-built clubhouse.

The Whitehall Club, as it was called on its launch in 1866, was rather unusual. Its target market was the largest group of affluent individuals with disposable income in the Westminser of 1860s: builders.

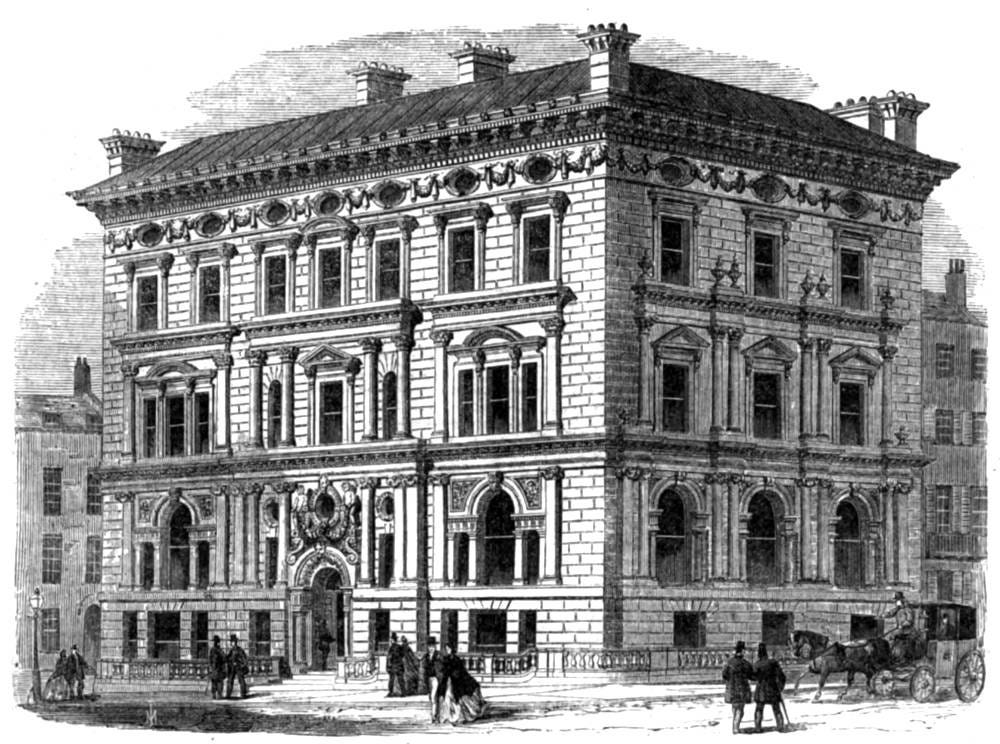

The Illustrated London News noted on its opening in January 1866:

This new association has no political character, but is chiefly composed of the leading engineers, contractors, and other men of business having frequent occasion to resort to the neighbourhood of the Houses of Parliament and of the Government offices in Whitehall.

This was important. It should be borne in mind that much of Westminster in the 1860s resembled a building site: the Great Fire of 1834 had almost totally obliterated the old Houses of Parliament, and the construction of the current Palace of Westminster took over three decades, continuing until the late 1860s. There was also a simultaneous rationalisation of ministerial offices, for instance, with the periodic rebuilding and patching up of the War Office, then on Pall Mall (on a site now occupied by the Royal Automobile Club). Consequently, the Whitehall Club’s founder members were the beneficiaries of a vast construction boom - but it was already coming to an end, just as the clubhouse opened.

The Whitehall Club, on its opening in 1866, sketched by M. F Manning. (Picture credit: Illustrated London News, 13 January 1866, p. 48/VictorianWeb.)

Defending the apolitical character of their club in the heart of Westminster, the membership was opened up to civil servants - but as other, more established clubs already appealed to civil servants, the Whitehall Club struggled to carve out a distinctive niche.

Charles Octavius Parnell was the original architect. Parnell was a significant architect in several respects. He had already designed (with Alfred Smith) a noted clubhouse - the Army & Navy Club, whose clubhouse stood on Pall Mall from 1851 to 1962. While it was ultimately demolished for what was felt to be a poor use of space (with more room given over to entry halls than to useable clubrooms), its grand architecture was much admired. Like the later Whitehall Club, it took after Charles Barry’s Reform Club, in pursuing an Italianate palazzo exterior, with an interior more modelled after the fashionable English country houses of the day. The other way in which Parnell was significant was as an influential architect of banks, such as the London & County Bank, completed in 1862 at 18 High Street in the City of London - I have long postulated a link between club architecture and bank architecture in the late 19th century, and Parnell was one of the most obvious overlaps, practising in both areas and adapting common styles.

Charles Octavius Parnell and Alfred Smith’s Army & Navy Club on Pall Mall (1851-1962), the clubhouse Parnell built prior to the Whitehall Club, as depicted in a contemporary print. (Picture credit: author’s own collection.)

In 1906, the Whitehall Club moved to the vicinity of Storey’s Gate: the exact address, 10 Prince’s Street, no longer exists, with the Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre now standing on part of the site.

With the papers of the Whitehall Club not having survived, the precise reasons for the move are unclear; although it is likely to have been a reluctant move: clubs occupying purpose-built clubhouses on prime real estate tend not to move voluntarily, so financial factors are likely to have played a part.

The move would have been convenient for members in one way, however. The period 1908-17 saw the construction of what is now known as the Government Offices, Great George Street (GOGGS). This vast complex, now encompassing the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) and HM Treasurry (HMT) also housed other government departments at the time, including the Home Office, and the India Office. Offices in this location had first been proposed in the 1860s - and indeed the looming prospect of their construction would have been on the mind of the Whitehall Club’s founders - but this initial scheme ran into trouble. As the government’s official history notes:

General agreement about the need for a new War Office building first led to proposals in the late 1850s for its inclusion in government offices in Downing Street, then in the late 1860s for a new building on Great George Street to house both the Admiralty and War Office. Factional opposition in Parliament, as well as concerns over the status of the Commander-in-Chief vis a vis the Secretary of State, delayed matters further. In the late 1870s, an Embankment site was proposed but a financial crisis put an end to that scheme

The construction of GOGGS provided one last major construction project which would have engaged the building tycoons of the Whitehall Club, and the move to Storey’s Gate would have been conveniently close, but not as exposed to the building site as 47 Parliament Street.

World War I proved difficult for many Edwardian-era clubs, with conscription depriving them of the presence of members and staff alike; and food rationing from 1918 dented the clubs’ hospitality offering. Many clubs closed down, either during the war, or in the years immediately following - and the Whitehall Club was no exception.

The Club folded in 1920, with its membership merging into the St. Stephen’s Club. With the St. Stephen’s Club being an avowedly political club - one of the main Conservative Party-affiliated clubs of the day - this was a final surrender of the project for an apolitical club in the heart of Westminster; but it did allow Whitehall Club’s members to maintain a presence in the area: until 1962, the St. Stephen’s club-house was directly opposite Parliament, on the site of what is now Portcullis House.

The St. Stephen’s Club’s clubhouse from 1870-1962, into which the Whitehall Club’s membership merged in 1920. The clubhouse as photographed in 1875. (Photo credit: Leonard Bentley, via FlickR.)

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

I'm so pleased to see this article: CO Parnell is a forbear of mine. He's been badly treated by history: as well as the Army & Navy Club, other losses to a Philistine age include his Palatine Club in Liverpool, and his London & County Bank in Lombard Street, in Italian palazzo style. The bank in your link is in Aldersgate by his son CJ Parnell, who also designed the (still extant, now a restaurant and offices) Yorkshire Club in York. So your interesting link between banks and clubs, both exuding Victorian respectability and solidity I feel, is well supported.

Best wishes.

I had no idea! How cool.