Lost Clubs: The Pioneer Club (1892-1939)

A ladies' club at the forefront of late Victorian social reform, which suffered a long, slow decline in the early 20th century

A colourised photograph of the interior of the Club’s Grafton Street clubhouse, pictured in Cassell's Magazine, 1 December 1897. Note the motto emblazoned near the ceiling, “LOVE THYSELF LAST.” (Photo credit: Wikimedia; colourised with the Kolorize.CC app.)

The Pioneer Club was one of the most notable Victorian ladies’ clubs in Mayfair. Frequently the subject of press coverage - often villifying it - the Club was associated with the ‘New Morality’ of the late 19th century, including feminism, temperance reform, anti-vivisection, and anti-vaccination. The Club was also unusual for its time in being open to women of all classes - although its Mayfair location ensured that the emphasis remained upon high society.

A colourised photograph of afternoon tea at the Club’s Grafton Street clubhouse, pictured in the Graphic, 1908. (Photo credit: Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 97; colourised with the Kolorize.CC app.)

Objectives

The Club claimed its name from American poet Walt Whitman, and his 1865 poem Pioneers! O Pioneers! A frosted glass partition in the Club’s front hall carried the following abridgment of phrases from the poem (which was not a direct quotation):

We the route for travel clearing

Pioneers, O Pioneers!

All the hands of comrades clasping

Pioneers, O Pioneers

The Club had American connections beyond its choice of name. In 1889, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs was formed in the USA - the only club in the UK which belonged to it was the Pioneer Club. The GFWC’s founder remarked that the Pioneer, “Grew more upon the lines of clubs of women in America than most of the women’s clubs in England.”

In its late Victorian and Edwardian heyday, the Club had a reputation for progressive politics and close identification with social reform. Erika Diane Rappaport believes that as a result, “Both proponents and critics of changing female roles believed the Pioneer was the cradle of the New Woman.”

Unusually, the Club practised what it preached on temperance reform, and was reportedly the only temperance club in London, declining to serve alcohol. It did, however, include a Smoking Room - a common feature among ladies’ clubs, which often made a point of defying Victorian conventions against women smoking.

Men were allowed as guests and as speakers, but were not allowed to visit more than once a month - with exceptions made for the husbands of members. The Club did, however, employ plenty of male staff.

A colourised photograph of the weekly Thursday evening debate at the Club’s Grafton Street clubhouse, pictured in the Graphic, 1908. (Photo credit: Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 97; colourised with the Kolorize.CC app.)

The Club saw itself as dedicated to serious, scholarly study, including a lecture room for regular talks and debates, and a “silence room” which survived across multiple changes of premises. It also published a quarterly journal, The Pioneer.

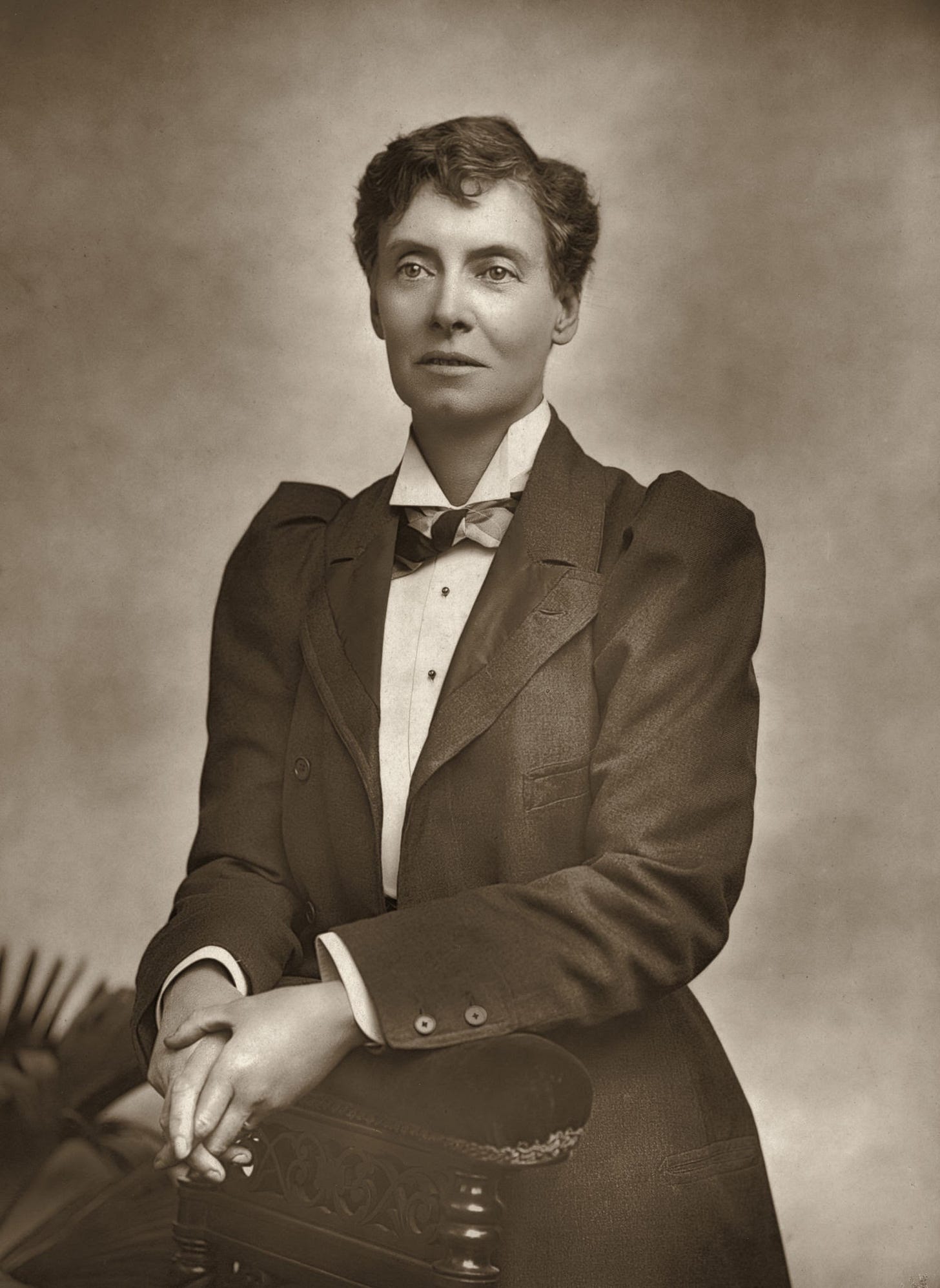

Emily Langton Massingberd (1847-97), founder of the Pioneer Club. (Photo credit: author’s collection.)

The founder, and her early death

The Club was founded by wealthy heiress and social reformer Emily Langton Massingberd. Erika Diane Rappaport writes that she “spent much of her income and energies on the temperance movement, women’s suffrage, and her own bid for a seat on the newly formed London County Council.”

The death of Massinberd’s husband in 1875, when she was aged just 27, left her in possession of a large inheritance; as did the death of her father in 1887. She put her inheritance to use on her social and political campaigns - and on the Club. Her “masculine” mode of dress, much commented upon in contemporary press coverage, was often invoked in descriptions of the Pioneer Club’s reputation for progressive politics, particularly by the Club’s male critics.

Like many other ladies’ clubs of the late Victorian era, the Pioneer Club was financially dependent upon a wealthy patroness. However, Masssingberd’s premature death in 1897, from complications of an operation at the age of 49, did not lead to the dissolution of the Club - as was the fate of so many other clubs dependent upon the charity of one individual. This was because Massingberd made generous provision for the Club in her will; indeed, within months of her death it moved to larger premises on Grafton Street, one of the most socially prestigious addresses for women’s clubs in the late Victorian era.

Lady Elizabeth Cust (1830-1914), who became chairman of the Pioneer Club after Massingberd’s death in 1897. (Photo credit: Paul Frecker.)

Nevertheless, the period after Massingberd’s death proved fractious. A number of members were dissatisfied with the Club’s direction after her passing, and formed the breakaway Grosvenor Crescent Club. This was because prior to Massingberd’s death, the Club had planned to move to 15 Grosvenor Crescent in Belgravia. A membership backlash against the move saw Lady Elizabeth Cust appointed chairman and treasurer, with the Pioneer Club remaining in the Mayfair area under her leadership.

Meanwhile, a breakaway group led by Leonora Philipps went ahead with the move, forming the splinter Grosvenor Crescent Club which operated until 1910, with decreasing political involvement so that by the 1900s it was a purely social club.

Without Massingberd’s leadership and patronage, the Pioneer Club gradually \lost some of its early drive and purpose, though it was still a centre for reforming lectures well into the 1910s.

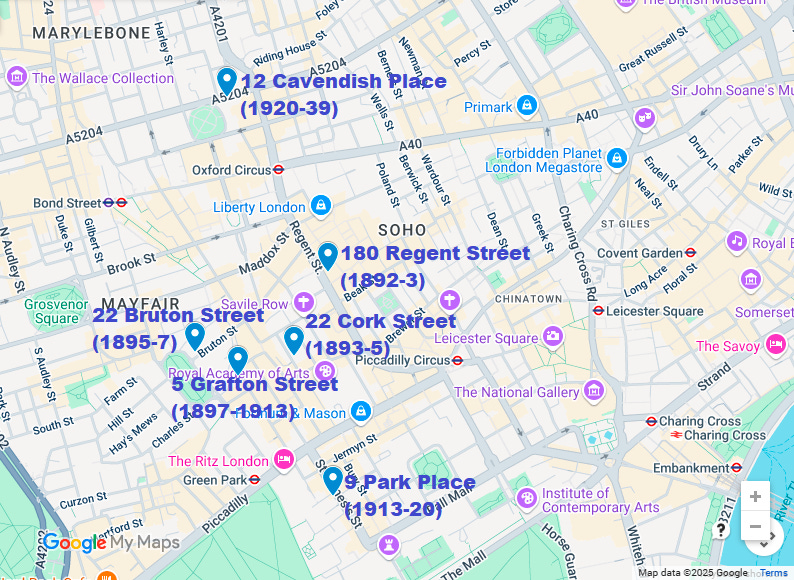

The shifting location of the Pioneer Club. (Picture credit: base map from Google Maps.)

Changing premises

The Club had a peripatetic existence, occupying six clubhouses across its 47-year existence. The very first clubhouse, occupied for just the initial year of its existence, was over the shop parade at 180 Regent Street from 1892-3. Like many ladies’ clubs of the era, it was particularly conveniently located for the shops of Regent Street and Oxford Street, where female club members could exercise their financial independence. According to Peter Gordon and David Doughan, these premises were:

“over a perfumer’s shop, where it had a drawing room and visitors’ room, separated by doors that could be folded back to make one room for debates and discussions, a tea room doubling as dining room, a dressing room and a reading room. There was also an unspecified number of bedrooms for members’ use. Mottoes were displayed prominently: ‘Silence is Golden’ (in the reading room), ‘In great things Unity, in small things Liberty, in all things Charity’, ‘They say - what say they? - Let them say’, and most prominently, ‘Love thyself last’. An allegorical painting of a female figure entitled ‘The Birth of a Planet’ by a Mr Maskell, a gift to the club from Mrs. Massingberd, was displayed above the mantelpiece.”

The original clubhouse building at 180 Regent Street, pictured in 2024. (Photo credit: Google street view.)

In 1893, the Club moved south to 22 Cork Street in Mayfair, where it remained until 1895. (The building has long since been demolished.) It then moved to another nearby Mayfair address, 22 Bruton Street just off Berkeley Square, which it occupied for another couple of years from 1895-7.

The 22 Bruton Street clubhouse, pictured in 2024. (Photo credit: Google street view.)

It then found a longer-term home in the heart of “Ladies’ Clubland” at 5 Grafton Street, where it remained for 16 years, from 1897-1913. In these premises, the Club prominently displayed a Frederic Remington sculpture, ‘Pioneer Woman’, depicting a North American frieze, which was presented to it in 1897.

The 5 Grafton Street clubhouse, pictured in 2024. (Photo credit: author’s own photograph.)

The Club moved to 9 Park Place - a few doors along from Pratt’s and the Royal Over-Seas League - where it remained from 1913-20. (The building was subsequently demolished.)

In 1920, the Club moved to its northernmost location - still close to the shops of Oxford Street - at 12 Cavendish Place, just off Cavendish Square, which was to be its final clubhouse, remaining there until its dissolution in 1939.

The Club’s final home, at 12 Cavendish Place from 1920-39, pictured in 2022, with The Langham visible in the background. More recent pictures from 2024 show the building abandoned and boarded up. (Photo credit: Google street view.)

Later years, and dissolution

By the inter-war years, the Club was operating in diminished circumstances. It had lost much of its earlier dynamism, and increasingly became a purely social club. Its membership slowly dwindled, though was momentarily bolstered in 1928 when the Ladies’ Imperial Club closed down, and merged into the Pioneer Club.

The Club struggled on through the 1930s. Doughan and Gordon note that it continued “a modest existence” through the 1930s:

“However, in November 1939 it was resolved that since the club could no longer meet its liabilities, it should be wound up, which marked its effective end (although for various reasons the company was not officially dissolved until 1961).”

The remaining members merged into the Sesame Club on Grosvenor Square. That, in turn, wound up in 1964.

Further reading

David Doughan and Peter Gordon, Women, Clubs and Associations in Britain (London: Routledge, 2006).

______________________________, ‘Pioneer Club’, in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007, rev. 2025).

Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.