In its late-Victorian and Edwardian heyday, the Empress Club was Mayfair’s premiere ladies’ social club, offering opulent facilities for independent-minded women. But it was rocked by repeated scandals and other difficulties, including suicide, bankruptcy, and fire, and it ended up becoming one of many Clubland casualties of the 1950s.

The former Empress Club building today. (Photo credit: Collins Construction website.)

Origins

The club opened in April 1897 as a proprietary club. Its owner, Otho Oliver, drew inspiration from two sources. The first was the general interest in the wave of women’s clubs which opened across London’s West End from the 1870s onwards, earning the three adjoining streets of Albemarle Street, Dover Street and Grafton Street the sobriquet of ‘Petticoat Alley.’ These focused on allowing Victorian middle-class and upper-class women to entertain when shopping in town - and were located close to the shopping precincts of Oxford Street and Regent Street.

Otho Oliver’s second source of inspiration was based on more immediate experience: his older brother Gilbert Oliver was a perfume merchant who in 1894 had opened the Tea and Shopping Club (later renamed the Ladies’ County Club) on Hanover Square, and had seen it rapidly become a chic establishment. Seeking to replicate its success in the heart of ‘Petticoat Alley’, Otho Oliver found premises in Dover Street.

The Empress Club’s original building, for its first year of operation from 1897-8, was at 32 Dover Street. (Author’s own photograph, taken in 2024.)

Membership

Peter Gordon and David Doughan write in their Dictionary of British Women’s Organisations, 1825-1960:

“Its membership consisted largely of ladies from aristocratic families, including the feminist activist Princess Sophia Duleep Singh.”

While the building contained suffragists, it was conspicuously apolitical - suffrage activity on ‘Petticoat Alley’ was much more likely to be focused around the organisations hosted by the Ladies’ Athenaeum, which from 1907 occupied the Empress’ former clubhouse and the adjoining building, at 31-32 Dover Street.

The Club flourished in the late-Victorian and Edwardian era. By 1898, it had 2,700 members, and by 1901 its membership had grown to 4,000.

Elizabeth Crawford shows how the 1901 census gives an insight into who was living at the Club:

“On the night of the 1901 census Otho Oliver, the owner and club secretary, was living on the premises, together with a female manager and a large domestic staff, comprising around 40 female and 12 male servants (including an engineer). There were around 30 women guests staying at the club, as well as several family groups, including husbands.”

The Morning Room of the Empress Club, photographed in 1899. (Photo credit: Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 95.)

Buildings

For the Club’s first year of operations in 1897-8, it opened a clubhouse at 32 Dover Street, the former London townhouse of the Earls of Mexborough. While a substantial building, described by Country Life at the time as “a very fine one”, Oliver nevertheless had more ambitious plans for a purpose-built complex offering extensive facilities, and so this building was merely a stopgap until work was complete on the nearby 35 Dover Street clubhouse.

The Empress Club’s home for most of its existence, from 1898 to 1955, was at 35 Dover Street. (Author’s own photograph, taken in 2024.)

35 Dover Street was to serve as the home the Club in several incarnations, for almost the rest of its existence, from 1898 to 1955 (barring an interval in 1910-1, which I will come to). Doughan and Gordon describe it as, “One of the most luxuriously appointed clubs in London.” It was designed by John Thomas Wimperis & William Henry Arber, who were best known for building theatres, from Blackburn to Plymouth, but who in 1891 had also designed the nearby Grafton Gallery on Bond Street.

The building had seven storeys above ground, plus a further two storeys below ground, and embedded a further building at the rear, at 15 Berkeley Street. Its facilities included a grand dining hall, a separate dining room, a tea room, a smoking gallery, a smoking room, several card rooms, 12 reception rooms, and 100 bedrooms. Gentlemen guests could only be admitted to the dining room, tea room and smoking room. On its opening, the bedrooms were available for a minimum of 4/-, with 1/6d extra for a coal fire. Afternoon tea cost 1/-, and was served with an orchestra playing in the background.

The presence of a smoking room and smoking gallery allowed ladies to smoke - something that was still considered controversial at the time. At the time, respectable society often frowned upon the idea of women smoking. In response, ladies’ clubs such as the Empress would emphasise their smoking offer as an assertion of independence, while magazines like Punch would use the trope of smoking ladies as something to attack ladies’ clubs.

The Grand Dining Hall of the Empress Club in the Edwardian era. (Picture credit: Elizabeth Crawford, womanandhersphere.com)

On 29 June 1901, Queen magazine wrote a gushing description of the new drawing room:

“[Its] walls, mirror frames and ceiling are in white, the graceful effects of molding being given by means of patent Daekoria, by which excellent reproductions of this kind of decorative work of all periods may be obtained. The panels of the walls, the hangings, and coverings of the furniture are in crimson Beresford brocade, and the comfortable chairs and lounges, tall, cool palms and tasteful screens make this withdrawing room the ideal of comfort for the rapidly increasing race described by our transatlantic cousins as club women.”

(Quoted in Erika Diane Rappaport, Shopping for Pleasure: Women in the Making of London’s West End (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 254n.)

A cross-section of the clubhouse, with the front at 35 Dover Street (left), and the rear at 15 Berkeley Street (right) showing the size of the complex behind the facade. (Picture credit: Collins Construction website.)

Turmoil in 1905-1911

Although the Empress Club remained an extremely fashionable club, it appears that its orignal owner, Oliver Otho, had built it on a house of cards. Litigation against him in 1905 from Baron de Bernice, over the commission on a £10,000 loan, ended in a 1906 High Court order which pushed for the forced sale of the Empress Club - something which was still being advertised as looming in 1907, and in 1908. In the meantime, the Club’s ownership was in the hands of a receiver. The sale proceeded in 1908, and included a separate auction of many of the Club’s possessions.

Otho Oliver himself was declared bankrupt in 1910. Oliver was absent for his bankruptcy hearing, where he was described as a “club proprietor” who was “lately carrying on business at 51A New Bond Street” (which was the address of his brother’s nearby perfume emporium). He seems to have fled the country: the judge noted that his “present residence the Judgement Creditor is unable to ascertain”, and I have not been able to find any trace of his whereabouts after 1910. As he was not included in the 1911 census, he may well have left the country.

In the interim, the Club under its new management relocated for part of 1910-1911 to 2 Burlington Gardens, one and a half streets away. (That building was demolished prior to 1926.)

Little wonder, given all this turmoil, that Elizabeth Crawford highlights how the Club seemed to be operating in diminished circumstances compared to a decade earlier, with the 1911 census suggesting live-in staff at the Dover Street clubhouse had shrunk from 52 to 25, and the number of overnight guests from 30 to 14, all of them women.

Change in ownership

In the spring of 1911, the following advert was taken out in several newspapers:

“NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the premises No. 35 DOVER STREET and 15 BERKELEY STREET, formerly occupied by the Empress Club have been acquired by the UNITED ARTS CLUB for the use of its Members, and the Club premises are NOW OPEN.

“THE EMPRESS CLUB has been closed and has ceased to exist. The Proprietors of the UNITED ARTS CLUB have no connexion with the persons formerly carrying on the Empress Club, and have not received, and accept no responsibility for Entrance Fees or subscriptions paid by members or proposed members of the Empress Club prior to the 27th May, 1911. Applications, therefore, as to the repayment of or otherwise as to such entrance fees and subscriptions should be made to the persons to whom the same were paid.”

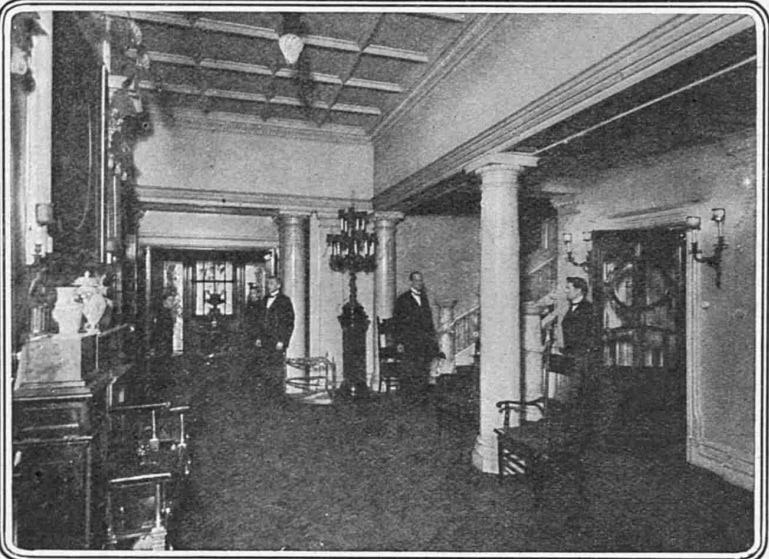

The renovated vestibule of the Club, for its 1912 re-opening. (Photo credit: The Sketch, 5 June 1912.)

The United Arts Club was a ladies’ club which had been operating since 1905 a few doors away, at 10 Dover Street. While they were initially keen to distance themselves from the fled Otho Oliver, not least to disclaim any financial liability, this did not last. In June 1912, they had a relaunch of the clubhouse, calling it the New Empress Club. Promotional material for the relaunch tapped into the branding and identity of the old Empress Club. Although the Club’s legal name continued to be the “New Empress Club” for several years thereafter, contemporary press coverage suggests that it was usually known simply as the Empress Club, and by the end of World War I, this was the only way anyone would refer to it.

The grand dining hall of the Club, as the time of its 1912 re-opening. (Photo credit: The Sketch, 5 June 1912.)

World War I

When war broke out, the Empress Club threw itself into various initiatives in support of the war effort. In October 1914, it provided office space to the Red Cross. The following December, the Club’s Emergency Voluntary Aid Committee (EVAC) chaired by Lady Shackleton organised a bazaar in aid of soldiers and sailors. By 1915, the EVAC was running a scheme to distribute toiletries to soldiers on the Western Front - a so-called “Tubs for Tommies” scheme originated by the Club’s Honorary Secretary Mrs. M. James Burns, which ran until 1918. A Red Cross hut was built on the roof in 1917. Receptions were also held for welcoming American officers that year.

Inter-war years

After the Great War, the Empress Club seemed to struggle, as many London clubs did. The events became more formulaic and predictable, and the bedrooms were increasingly filled by permanent residents.

By the inter-war years, it was more a site of scandal than high society: newspapers reported a 1934 case of anti-Suffrage campaigner Lady Griselda Cheape, who was found dead in her bath in the Club. There was another widely-reported death at the club later that year: 37-year-old Scotswoman Marjerie Augusta Kennedy-Erskine, who had committed suicide in her room on Christmas Day.

World War II

When World War II broke out, the Club resumed the kinds of patriotic activities seen in the previous war: Lady Elibank established “a centre for collecting money and material for comforts for the troops” in November 1939.

However, the Club was to suffer a crippling blow during the Blitz, being damaged in 1941. While it was not directly hit by a bomb, many of the neighbouring buildings were impacted, and the fire spread to the Empress Club.

Another of the many clubs hit during the Blitz was the Royal Societies’ Club on St. James’s Street, which suffered a direct hit. A merger was hastily arranged between the two, and the newly-renamed Empress and Royal Societies’ Club operated from the Dover Street clubhouse from 1941. The arrangement was something of a marriage of convenience: the Royal Societies’ Club - which as the name implies, was comprised of fellows of the learned societies - was a gentlemen’s club, whose male members diluted the raison d’etre of the Empress Club as a ladies’ club, just as the Empress Club diluted the raison d’etre of the Royal Societies’ Club as a fellowship of learned society members. Neither seems to have had much in common with the other, beyond splitting the cost of sharing the same building.

There were attempts at renovating the Club in more modern decor after the war, with a Persian room opened in 1949, which served as a cocktail bar.

Closure

By the 1950s, the Club’s large premises housed a rag-bag of different groups - the attic had been let out to the Variety Club of Great Britain since 1950, making it particularly popular with actors. Many of them availed themselves of the looser scrutiny of a private members’ club to engage in gambling - even when it was illegal. This practice continued for several years.

In 1955, the Club was raided under the Betting Act, and nine men were arrested for illegal gambling on the premises, including popular comedian Tommy Knox of the ‘Crazy Gang’, who was remanded in custody. Knox was bound over to keep the peace, and the Club’s owners, Empress (Berkeley Square) Hotels, were fined £75.

In the aftermath of the raid, and a wave of negative publicity portraying the Club in a seedy light, it dissolved later that year, and the building was sold off.

Fate of the clubhouse

After the sale of the building, it had a varied existence. Much of it was turned into offices in 1955, while the grand dining hall in the basement became a nightclub. In 1961, the nightclub was converted to the Empress Restaurant. Shops continue to occupy the ground-floor arcade.

Collins Construction are currently renovating the main building. Their website states:

“35 Dover Street has most recently been multi-let to office and luxury retail tenants, and the fit out will see the repositioning of the building to create a workspace for today’s commercial market.”

Their plan is to rename the redeveloped building ‘The Empress.’

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.