The American Club on Piccadilly only existed for 72 years; but it rapidly became an integral part of the London club landscape.

The American Club building at 95 Piccadilly, on the corner of White Horse Street. The boarded-up door on the left, on White Horse Street, was the main entrance. (Picture credit: Brian Mawdsley, via Historic England website.)

Origins

The Club was set up for expatriate Americans in London. It followed - and was modelled on - a long history of 19th century clubs for expatriate groups in the capital, including those for French, German, Indian, Norwegian, and Swedish citizens.

It was part of a wider move towards clubs embracing Americans in London during the closing phase of World War I: US entry into the war in 1917 had increased the number of Americans in the capital on war business, and Buck’s had been founded in 1919 as a wartime reunion club for army officers, with a sizeable American contingent.

The American Club was without permanent premises for its first year, but funds were raised to secure a building. US Ambassador to London John W. Davis formally opened the clubhouse on 14 July 1919. There were 300 founder members - 200 London-resident members who were American by birth, plus 100 Londoners with “American connections” who were associate members.

It was conceived and executed as a “gentlemen’s club”, and remained so throughout its history, resisting the admission of women or any amalgamation with the American Women’s Club - which had actually pre-dated the American Club, having been set up in 1898, and being based at the time in a clubhouse on Grosvenor Street. The American Women’s Club was a much larger establishment, with 1,500 members by the 1920s.

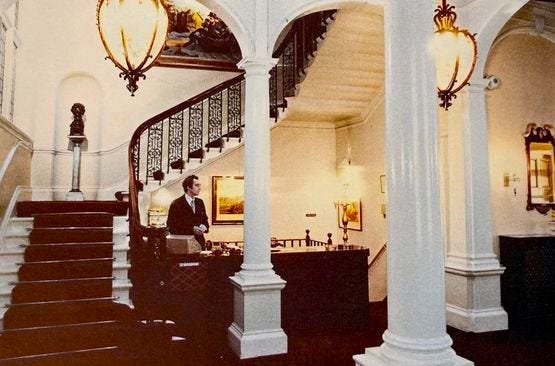

The main lobby on the ground floor of the Club pictured in the 1970s, and colourised with the Kolorize.CC app. (Photo credit: Malcolm Lewis, in Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen's Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1979).)

The Club

By the 1960s, the Club had grown to 800 members, half of whom were based overseas, making it a smaller-than-average London club (although it still had a much larger membership than many comparable US city clubs).

Charles Graves noted that the Club’s food had a “transatlantic flavour”, with popular options including “corn on the cob, corned beef hash, Hawaiian chicken and cherrystone clams”, and an annual New Year’s Day egg-nog party for members, offered on the house. Graves also observed that the general choice of alcohol was more British than American, with members favouring Scotch whisky over rye or bourbon.

The membership focused around US executives based in London - Woolworth’s consistently had directors among the membership for most of the Club’s existence. There were also numerous airline pilots who flew into London, thanks to a corporate membership scheme with Pan Am. The Club also had a long-standing policy of extending honorary membership to various US diplomats in London, including the Ambassador; and from 1967 it awarded honorary membership to the incumbent President of the United States, with Presidents Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan and Bush Sr. all having accepted.

The first-floor dining room of the Club pictured in the 1970s, and colourised with the Kolorize.CC app. (Photo credit: Malcolm Lewis, in Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen's Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1979).)

The building

The 1,182m² building dates to 1886, designed by Alfred Lovejoy of Roper & Lovejoy, in a Franco-Flemish inspired design. It consists of four main storeys, plus a basement, and a gabled attic. It was approached from the side, by an entrance on White Horse Street.

It had been the London home of Conservative MP Sir Bertram Falle and his wife Lady Mary Falle, née Sturgis, a Boston heiress who was the daughter of Russell Sturgis, the opium magnate who later became head of Barings Bank. In 1919, the Falles agreed to sell to the new club their house, which had 77 years remaining on its lease.

The Club’s layout emphasised card games. The ground floor had a main lobby, a white-and-gold Reading Room overlooking Piccadilly and Green Park, and a Bridge and Gin Rummy Room; the first floor contained the main Dining Room, as well as the olive-and-green American Bar; while the second floor contained the Poker Room, Committee Room, and three of the bedrooms; the remaining three bedrooms were on the third floor. It has been Grade II listed since 1972.

The ground-floor drawing room of the Club pictured in the 1970s, and colourised with the Kolorize.CC app. (Photo credit: Malcolm Lewis, in Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen's Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1979).)

Closure

The Club faced many of the same difficulties of other London clubs in the 1960s and 1970s, but its closure was not inevitable. Although it never had a particularly large membership to begin with, and membership had dwindled to just 400 by 1989, it did not experience financial collapse; nor did its lease - which was due to run until 1996 - run out.

Instead, the Club failed to plan ahead around its lease provisions. It had been the long-term beneficiary of a peppercorn rent fixed in the 1920s, but this agreement was due to expire in 1990. When the new freeholder sought to negotiate a commercial rent, the Club’s members belatedly realised that they could not afford this, and had not made any alternative provision for relocation, either, and so the clubhouse was closed down in 1990. Realisation of the gravity of the situation all came on very suddenly - as late as 1989, the Club was still recruiting new members, at £125 a year’s subscription, with a £100 joining fee.

Its fate can therefore be contrasted with the fate of the Naval and Military (“In & Out”) Club next door, which faced a similar predicament with the same new freeholder in the 1990s, but which successfully managed to turn that situation around into a move to new premises.

The American Club did not formally merge into any other club, but a number of its members joined the In & Out Club next door. Tim Newark’s history of the In & Out quotes Captain Nick Kettlewell:

“I was Chairman of Membership [at the In & Out Club] and we looked at who they had. Their Secetary suggested we take in ‘The Ivy League’ and not their group or corporate members such as all pilots of Pan Am. This we did. We had to stock up the bar with bourbon and rye and slightly amend dress regulations as Ivy League Americans consider blazer and flannels to be superior to a suit - suits being worn to the office by those who have to work!”

The possessions of the American Club were auctioned off in 1996 for £87,446.

Fate of the building since the closure of the Club

The building’s fate has very much been tied to the neighbouring properties on the same street block, the Grade I-Listed Cambridge House (the former “In & Out Club” building) at 94 Piccadilly, and the Grade II-Listed Green Park Chambers at 90-93 Piccadilly.

As long as both neighbouring clubs had occupied buildings on Piccadilly, the freeholder had been Sir Richard Sutton Estates. However, in January 1989, Sutton Estates sold the freehold to the Al-Marzouq family of Kuwait - who sought to run the estate upon more commerical lines, noting that the lease of both neighbouring clubs was due to expire in the late 1990s. In 1991, they applied to Westminster City Council for permission to convert the whole area into a luxury 110-bedroom hotel - and with a view to this, they signalled that they were not interested in renewing the In & Out Club’s lease beyond 1999 (which was what ultimately led to the In & Out Club agreeing to vacate that year). In the event, in 1996 the freehold for the entire estate was sold on to Syrian billionaire property developer Simon Halabi (then ranked #14 in the Sunday Times Rich List), for a reported £50 million. Halabi’s companies announced an intention to redevelop the site into a hotel, and there was press speculation in the following years that the site could also see nightclubs, luxury private mansions, a spa and a casino. In the meantime, the site remained vacant and boarded-up, and fell into disrepair - particularly the American Club building, whose condition was given by Historic England as “poor” and it was put on the “at risk” register, suffering from extensive water damage and dry rot.

The state of the building and its interior in 2013. (Picture credit: Daily Mail.)

Eventually, after Halabi was declared bankrupt in 2010, the estate fell into receivership. The estate was then sold for a reported £130 million in 2011, on behalf of Allsop LLP as LPA receivers, to Aldersgate Investments, an investment vehicle owned by Simon and Jamie Reuben, who made their fortune in the Russian aluminium trade in the 1990s before branching out into real estate and hospitality. They are currently ranked #3 in the Sunday Times Rich List.

The Reuben Brothers’ original plan, which secured planning permission from Westminster City Council in April 2013, was to convert the American Club back into a single luxury private home. The Daily Mail speculated such a home could sell for £70 million.

The Reuben brothers subsequently applied in May 2017 for a revised plan for the estate, for which planning permission was granted in March 2018. This involves building a large 6-star hotel and residences around Cambridge House, while 94 Piccadilly itself will return to use as a private members’ club, due to open in 2026 (as “Cambridge House”), and the nearby Green Park Chambers at 90-93 Piccadilly will include a shopping arcade. The hotel complex is to be operated in partnership with Auberge Resorts, owned by the US-based Friedkin Group.

95 Piccadilly (left), Cambridge House at 94 Piccadilly (centre) and Green Park Chambers at 90-93 Piccadilly (right), pictured in 2008 (top) and 2021 (bottom), showing the work done during this period. (Photo credit: Google street maps.)

Under these plans, the American Club building at 95 Piccadilly is proposed as part of the interconnected hotel complex, with the ground floor as a lobby area, while the first floor upwards are to contain hotel rooms. Other alterations to the building that were approved included the construction of a sub-basement, and “creation of a new entrance on Piccadilly (to the Club’s former cigar bar [the Reading Room]) to provide street access to a hotel bar .” This plan supersedes the previous plan to turn the building into a single private residence.

Marketing materials for the proposed development of the site. (Photo credit: Auberge Resorts.)

Further reading

Charles Graves, Leather Armchairs: The Chivas Regal Book of London Clubs (London: Cassell, 1963), pp. 155-157.

Anthony Lejeune, The Gentlemen's Clubs of London (London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1979) pp. 20-5.

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

1990. Sigh. Missed it by a few years.