Clubs are not – as widely assumed – limited to bustling metropolises like London and New York. They can also be found in some of the most remote communities on earth. It is arguably the central role of the club in bringing a community together that can make it a staple in these communities. This is particularly true of the clubs found in the Pacific Islands.

The British influence was central in exporting clubs to this part of the world. And the design and administration of these clubs tells us much of the British mindset and priorities during the years of imperial rule. Although British shipping routes had operated throughout the Pacific in the 18th century, it was only in the 1870s that the United Kingdom formalised its Pacific influence into formal colonies. This followed, in the decades after the 1857 Indian rebellion, a wholesale reorganisation of the British Empire, away from privateers, and towards direct involvement by the state. The Pacific Islanders Protection Act 1875 proclaimed many of the Pacific Islands formally under the control of the British government, enacted two years later through the appointment of a High Commissioner for the Western Pacific, to oversee these territories. The 1886 Anglo-German Agreement then formally partitioned many of the Pacific’s islands between the two respective empires. And whilst the Germans seldom exported clubs to their colonies, the British proved keen to do so.

The sign and current building building of the Lagoon Club in Ambo, Kiribati. (Photo credit: ‘The Weary Traveller‘, blogger.com.)

Many of these British Pacific clubs are in reduced circumstances – though their remains can still be seen across the region. A stark example can be found on the beach of Banraeba, a village on the islet of Ambo, making up part of the atoll of Tarawa, the capital of Kiribati. This was a British Protectorate (as part of the Gilbert Islands) from 1892, and a colony from 1916, until it achieved independence in 1979.

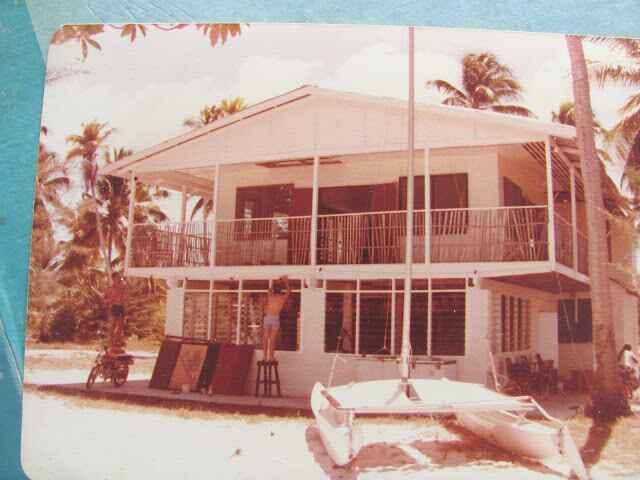

The Lagoon Club’s old clubhouse, prior to its collapse. (Photo credit: ‘The Weary Traveller‘, blogger.com.)

Visitors to Banreaba will find the Lagoon Club - or what remains of it. The Lagoon Club once had a two-storey clubhouse which sat at the end of a complex with tennis courts, a nine-hole golf course, and boats. But the building proved inadequate to the storm surges of Kiribati, and collapsed, to be replaced by the current Maneaba (open-ended building), which is used as a meeting house. The Club still offers a bar, swimming pool, volleyball, and a safe swimming lagoon. It also retains reciprocations with clubs worldwide, dating from its days as a colony.

The Ovalau Club in Levuka, Fiji. (Photo credit: ‘Friends of Levuka Historical & Cultural Society’ Facebook group.)

Another one-time colonial-era club is the Ovalau Club in Levuka, Fiji, which claimed dates to 1904. The British had first settled Levuka as a whaling outpost in the 1830s, but it expanded amidst a wave of penal migration in the 1860s, becoming a colony in 1874, with the colony’s first Indian indentured labourers arriving in 1879. After Fiji became independent in 1970, the Ovalau Club opened up to non-Europeans, and became a pillar of the local community. The Club went bankrupt in 2014, and never reopened, being locked in an ownership dispute, and then suffering damage from Cyclone Winston in 2016, exacerbated by subsequent looting. It nevertheless remains listed in Lonely Planet guides as a major historic landmark of Levuka.

The Ovalau Club undergoing rebuilding and repainting work in 2017. (Photo credit: ‘Street Beats‘ blog, Wordpress.)

There have been attempts at restoration. An experienced builder and project manager from Australia blogged about serious attempts at repainting and rebuilding work in 2017, but later reported having abandoned the project by the following year. A 2022 GoFundMe kickstarter attempted to raise funds, but only yielded $1,830 AUD of its intended $10,000 AUD goal.

The Defence Club in Suva, Fiji, pictured on its centenary in 2015. (Photo credit: Fiji Village.)

Fiji’s capital, Suva, hosts several other clubs. Until only a few months ago, the most formal was the Defence Club, founded in 1915, by a group of Fiji-based European men preparing to serve in the First World War, with the blessing of the colony’s Governor, Sir Bickham Sweet‑Escott. It occupied a building that had been constructed in 1901. The Club purchased its first billiard table in the inter-war years, bought from Sydney for £140, paid by Robert Crompton, a lawyer and former member of the Fiji Legislative Council.

The Club was initially a European bastion, but it opened up to Fijians decades before independence; its first Fijian member was Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna at an unknown date, but there is a record of his giving a speech at the Club on ‘The Fijian’s View of the European’ in 1939 - the text of which is here. Later Fijian members included Ratu Sir George Cakobau, Ratu Sir Kamises Mara, Fiji’s President Brigadier-General Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, and Ratu Edward Cakobau, the latter of whom also served as President of the Club. The Club remained men-only from Mondays to Thursdays, but had women members who were allowed to use the building from Fridays to Sundays, while Wednesdays were declared “Club night”.

The Defence Club’s Secretary and Manager in 2022, Raja Kumaran, standing behind the wooden Chandos counter. (Picture credit: RAMA/Fiji Times.)

The Club was noted for its ‘Chandos counter’. This once stood in the basement bar of the (now-defunct) Chandos Hotel at 29 St. Martin’s Lane, London, but was removed during a renovation in the early 1950s, and was placed on permanent loan to the Defence Club. The tradition of etching the table with names began among soldiers on leave in London during World War I, but continued over the decades, including after its installation in Fiji.

An interior view of the Defence Club, undated. (Source: Mapio.)

The Club maintained a snooker table, card room, and many of the trappings of traditional English clubs, such as an election process which used blackballing; although some things were updated - like the abolition of the chit system, which allowed members to buy drinks on credit and had been widely abused. The Club also lost the use of its bedrooms over the years.

(The Presidents’ wall at the Defence Club, Fiji, pictured in 2022. Picture: FT FILE/ RAMA/Fiji Times.)

Unfortunately, tragedy struck the Defence Club only a few months ago. On the morning of 26th February 2024, it was reduced to ashes by a devastating fire. The cause of the blaze remains unknown.

The poolside of the Fijian Club. (Photo credit: Fijian Club website.)

The Fijian capital still retains a number of clubs old and new, however. The oldest is the Fijian Club, dating to the 1880s, which offers its members a bar, restuarant with veranda, tennis courts, squash courts, swimming pool, gardens and bedrooms. It enforces a dress code adjusted for the climate - while shorts are permitted and ties are not required, “bare feet and bare torsos” are not tolerated; and all shirts must have a collar, except at the weekend.

The bar of the Roya Suva Yacht Club. (Photo credit: Royal Suva Yacht Club official Facebook group.)

The largest club in Suva today is the Royal Suva Yacht Club, dating to 1932, holding its first race that year, followed by a regatta in Levuka the ensuing year. Since 1976, it has hosted the Sydney to Suva Yacht Race. It offers a wide array of services.

Where clubs are more prevalent today in the Pacific - and generally in greater health than among former British colonies - is in Hawaii. The islands remained sovereign until near the end of the 19th century, retaining a monarchy until 1893, which was followed by the American invasion during a short-lived republic that ended upon annexation as a Territory of the United States in 1898.

The King Kamehameha Golf Club in Hawaii. (Picture credit: King Kamehameha Golf Club website.)

There are a wealth of golf clubs found across the islands today, most of them recent developments from the last few decades. Arguably the most visually striking clubhouse is that of the King Kamehameha Golf Club in Waikapu, Maui, based on Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1957 design for a house Arthur Miller wanted to build in Connecticut for himself and Marilyn Monroe, but which was unrealised due to the couple divorcing shortly after building began. The Hawaiian building was finally constructed in the early 1990s, opening as the Waikapu Valley Country Club in 1993, and then turning into the Grand Waikapu Golf Resort and Spa, before closing in 1999. The Club reopened in its current incarnation in 2006.

The view from the Pacific Club. (Photo credit: Pacific Club website.)

The oldest of the archipelago’s clubs, dating to the Hawaiian Kingdom era, is the Pacific Club in Honolulu, founded by expat English merchant (and later Prime Minister of Hawaii) William Lowthian Green, in 1851. Green had only arrived in Hawaii the year before, and initially established the Club as “The Mess”, to serve as uniting point for other English expatriates. In 1867, it changed its name to “the British Club“, and then in 1892 it settled on “the Pacific Club”. The Club moved to its present site in 1926. By the 1930s, it had absorbed Hawaii’s defunct University Club. For over a century, it remained a club for whites only, but opened up to all races in 1968. Women were admitted from 1984.

The Outrigger Canoe Club of Honolulu. (Photo credit: Alta Club website’s reciprocal club listings.)

Honolulu also hosts the Outrigger Canoe Club, dating to the earlier years of American occupation, in 1908. The Club was founded Waikïkï Beach, as a response to the then-near-extinction of the ancient Hawaiian water sports of surfing and outrigger canoeing. Abandoning its original clubhouse owing to a termite infestation of the wooden building, it settled on its current site in 1964. The Club is credited with the invention of Beach Volleyball. It has an appropriately relaxed dress code for the climate, with Hawaiian shirts welcome, and the stipulation that in most parts of the Club’s complex, some form of shirt is required after 6pm.

The clubs of the Pacific show their strong colonial - and particularly British - roots. They closely follow the membership structure of the traditional London clubs. Nevertheless, like all colonial clubs, they retain a unique blend of influences and cultures.