Good Chaps: The Rise & Fall of an Idea in Clubland

I recently read a fascinating interview with Simon Kuper, on Peter Geoghegan’s Substack, to publicise Kuper’s new book, Good Chaps. And I was struck by the echoes of what he has to say about the ‘Good Chaps’ theory, that was popularised by Peter (Lord) Hennessy, and its implications for Clubland:

These people thought the highest thing you could do with your life was public service. Coming from the top of society, they presumed their public service would be at the top of the state. They had a strong patriotic moral code, came from a small caste so they knew each other, and most of them weren’t going to steal from the state – so you didn’t need rules or laws to stop them from going to work for a company selling to government, or from meeting the Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro on behalf of a hedge-fund manager, as [Boris] Johnson did. Good Chaps (and World War One volunteers) like Attlee and Eden and Macmillan wouldn’t have done that. Their code wouldn’t have allowed it. Because they were bound by codes, they didn’t need rules. And so the British state doesn’t have many. As Peter Hennessy used to say, the state here works on the Good Chaps theory.

In other words, rules are only necessary when people cannot be trusted to do the right thing in the first place.

William Hogarth, ‘Midnight Modern Conversation’ (1733), which portrayed the mannerisms of informal clubs in coffee houses, at the birth of the club era, when there were minimal rules in place.

This has obvious London Clubland echoes, and it is worth looking at how the notion of “Good Chaps” has had parallels in clubs – and has been challenged. Early clubs of the 17th and 18th centuries stressed “clubbability” and “conviviality” – both important concepts, which I think are worthy of future standalone posts of their own. These involved an element of sociability and reliability in all members. But it should be remembered that they existed against a backdrop of the earliest London clubs being entirely run for profit by private landlords – London’s first member-owned club, the Union Club, would not be founded until 1799. Consequently, the emphasis was very much on how much a member could be relied upon to pay for their gambling bills and bar tabs. The sometimes sordid question of how the money for that was raised seemed of secondary importance.

This went hand-in-hand with an aristocratic social underpinning to many of these 18th century social clubs, which stressed the norms of good manners and codes of honour. And as per Hennessy and Kuper’s model, it was a tight-knit community where everyone knew each other – which increased the scope for immediately-felt consequences such as social ostracism. If we look at early club rulebooks, there was minimal emphasis on regulating behaviour. The first set of rules for White’s, adopted on its conversion from a coffee-house to a club in 1736, has just ten rules. Five of them were about the admission process for electing new members, three were about regulating attendance at meals and mealtimes, one was to set up the subscription, and one was to clarify the hours when gambling would take place. There were no rules around behaviour; though if contemporary accounts, and contemporary satire of White’s (reflected in the illustrations by Hogarth, and Gillray, as below) is anything to go by, early Clubland could have sorely done with some rules on behaviour. Nonetheless, the assumption was that noblemen did not require guidance, and certainly not anything as petit bourgeois as a set of rules around conduct.

James Gillray, ‘Anacreontick’s in Full Song’ (1801), spoofing the manners found in early clubs.

Many of these assumptions changed with the evolution of clubs in the 19th century. Beginning with the United Service Club in 1815 – London’s first club to be focused around a theme, rather than being of a purely sociable nature – the new clubs of the capital increasingly assumed a middle-class character. This was firstly of an upper-middle class nature (the United Service Club only admitted officers from the ranks of Major or Commander and above - and this was in an age when many army commissions were still routinely bought). Yet paralleling the successive extensions of the franchise through the 19th century, London’s Clubland became increasingly middle-class, and then lower-middle-class, as the century proceeded. Taking their lead from the Union Club – which saw itself as a sort of parliament of clubs, mirroring the composition of the UK – the clubs used its rulebook as a template, and notions began to evolve of “conduct unbecoming”, “injuriousness to the club”, and being “unfit to be a member.” These were, however, less informed by the changing class composition of club membership, and were more the product of bitter experience, as clubs invariably came to grapple with issues caused by misbehaving members.

It is worth acknowledging that the broadening base of London club membership was not simply a matter of social class. As clubs increasingly became ‘pillars of the establishment’ in the 19th century, they became increasingly preoccupied with propriety and reputation. Gone was the devil-may-care attitude of 18th century amateurs, and instead came a patchwork of venerable institutions that represented the organs of the British state: the universities (the United University Club, Oxford & Cambridge Club and the Athenaeum), the military (innumerable establishments including the Army & Navy Club, Naval & Military Club, Cavalry Club and Guards Club), the political parties (the Carlton Club, Reform Club, and National Liberal Club), finance (the City of London Club, and the Gresham Club), the legal profession (Law Club), agriculture (Farmers Club), and so forth.

Club membership became less a matter of sybaritic pleasure in discreet gambling rooms, and more a matter of service to the state. It was against this backdrop, with its implication of “Ask not what your club can do for you, but what you can do for your club”, that the ‘Good chaps’ theory reached its apotheosis in Victorian Clubland.

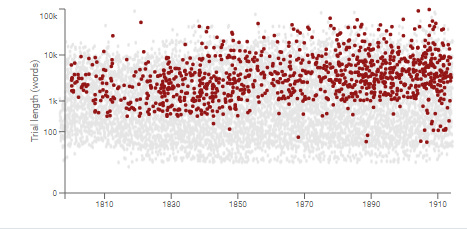

Yet the high ideals of the ‘Good chaps’ approach to clubs was never universally shared. For one thing, there was a general, unquestioned assumption that it would be shared by the non-members of a club who had little or no voice: the staff. Given that staff conditions could be highly variable and even outright poor, it is little surprise to find in the Old Bailey Online records that there were some 1,259 criminal cases involving clubs within the London area from 1800 to 1913, with increasing frequency over time. By far the most prevalent charge was theft, with other common charges being larceny, fraud, burglary and robbery. Although members were implicated as well, charges and convictions were far more common among staff. This also reflects long-standing trends within the hospitality sector across many cultures, of underpaid and overworked staff responsible for immensely valuable assets, being prone to temptations if left without adequate oversight.

Criminal cases involving clubs in London, 1800-1913, measured by the number of Old Bailey cases in which a club was named in proceedings. (Source: Old Bailey Online.)

While it was far rarer for members to be convicted of criminal offences involving their club, the challenge of the ‘Good chaps’ theory is not merely to be measured in something as stark as criminal charges. On a far subtler level came the matter of managing competing interests. It is entirely normal for an active member to throw themselves into the affairs of their club. It is also normal for them to volunteer huge amounts of time and skill. Is it reasonable for them to seek or accept some form of remuneration for their efforts? (Some clubs would categorically say “No”, and would view that as venal; others would insist that only by having a professionally remunerated Board of Directors can they reasonably expect professional standards of them, and secure the most rigorous outcomes. There is no “"right” answer in every context - especially as the needs of a 50-member dining society meeting once a month in one room may be very different from those of a 20,000-member club managing a 100-acre estate with an eight-figure budget.)

And then there is the matter of managing competing interests in a club. If a member runs a successful group – say, for the members of a social club who also like to play squash - are they not simply doing their job, advocating for that group to be as well-resourced as possible by the wider club? But a countering view may be that they are “hogging” the Club’s resources, at the expense of the non-squash-playing majority of club members; that they are using their position and patronage to reward their immediate circle, and to ultimately promote themselves and their own interests within the Club. Neither side is necessarily “right” or “wrong”. But these pressures are found in almost any club of any size, and the question of personal interest complicates matters.

And this is why club rulebooks, guidelines and procedures have become infinitely more complex over the last two centuries; not because having more rules necessarily equates with better governance, but because having no rules to cover a situation can lead to the worst outcomes of all.

Club rulebooks are also – it has to be admitted – generally inversely proportionate to trust in members. The more exhaustive they are, the less trust displayed to members to “do the right thing” if left to their own devices. As a dramatic example of this, I recently highlighted the 1870s rulebook of the Junior Carlton Club, which stipulated:

“No books, papers or periodicals that are the property of the club or supplied by the circulating library shall be taken into the lavatories. Nor may any member place his feet on any sofa or chair or wet umbrella into any of the rooms.”

A reasonable outsider may well ask themselves what kind of member needs to be told this, and have it spelt out in the rules? You also see parallels in areas like the growth of overly prescriptive dress codes, precisely specifying which garments may and may not be worn on the premises, possibly also depending upon the times of day, week and/or year, different rooms of the club, the overall temperature at a given time, and the personal intervention of one or more club officials. None of these dress regulations existed in London clubs prior to the 1950s – they were not deemed necessary, precisely on the ‘Good chaps’ assumption. And I would suggest that the existence of such rules is emblematic of the death of the ‘Good chaps’ assumptions, and the accompanying levels of trust.

Which leads to my final question: about separating out formal rules from cultural norms. Generally speaking, I favour the latter over the former. I am not suggesting an absence of rules. What I mean is that lengthy, formal, rigid, overly prescriptive rules can and do invariably generate friction – and not just from dogmatic, obsessive members, but even from the more light-heartedly mischievous armchair members; the kind of members who are not natural rebels, but who enjoy stirring things up. Most clubs have such members. Where I have seen clubs navigate these areas more amicably, it has been with a strong sense of leadership and direction around cultural norms, and respectfully offering members guidance around such norms. Such clubs still have broad discretionary rules granting the Club’s management broad latitude over enforcement of a wide range of areas. But it is not put to members in that way. Human beings are social creatures; club members doubly so. Members in most settings generally react much more amenably on being told, “It is a long-standing custom or norm to generally behave/dress in this way, in this part of the clubhouse”, than they do to being told, “Rule 36A precisely stipulates the minimum width of your lapels and tie, and the type of your shirtcuffs and collar, in the Smoking Room after 2pm on most weekdays, except the second Tuesday of every month.” It is a matter of learning from the best of the ‘Good chaps’ assumptions, and showing respect to members at all times. Since their earliest days, clubs have always sorely needed rules; but they should never feel oppressive.