Clubs in the work of James Gillray

Clubs recurred throughout the birth of the political cartoon

James Gillray (1756-1815) is widely regarded as “the grandfather of the political cartoon”, his topical etchings by turns witty, erudite, vulgar, and rendered with tremendous technical brilliance. He mocked all the great institutions of the day - and so it should come as little surprise that clubs featured as a recurring trope in his work, especially as he lived and breathed “Clubland.”

Gillray conveyed a remarkably consistent image of clubs across more than three decades of practice. Throughout his career, he had a ringside seat on the clubs of St. James’s, first living nearby on Old Bond Street, and then from 1797 until his death in 1815, living at 27 St. James’s Street - next door to Boodle’s, at number 28, and diagonally opposite from Brooks’s. Lodging in his attic room, he therefore not only had a prime view into the Great Subscription Room on the first floor of Brooks’s, where so much late-night gambling happened, but he was also well-placed to see members waddling in and out at all hours, in varying states of intoxication.

Here, I want to look at how early clubs were invoked as an image, through 10 satirical prints that Gillray produced, from the start of his career (1784) to near its end (1809). As the best-selling printmaker of his day, it tells us much about how clubs have been seen in art, and in popular culture.

What is not covered in this piece are puns, such as Charles James Fox in The Republican-Hercules Defending his Country (1797) holding aloft a club marked “Whig Club”, though the Brooks’s allusion in that print was certainly intentional. Nor does it cover the legion of prints he produced about the St. James’s and Pall Mall areas in general, with their shops and private homes. I am interested here in how Gillray rendered the clubs.

Returning from Brooks’s (13 April 1784)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Returning from Brooks’s (1784) is one of the earlier prints attributed to Gillray; we are not even entirely sure whether it is his work, because he changed his style quite dramatically in his earlier years, both in the name of experimentation, and to occasionally obfuscate his output so as to evade possible prosecution. The British Museum describes this work thus:

“The Prince of Wales, drunk, staggers along supported on his right by [Charles James] Fox, on his left by Sam House. He wears a 'Fox' favour and a Prince of Wales plume in his hat. Fox, whose left arm is linked in the Prince's right, points at him with his right forefinger. House (right) stands in back-view, turning his head to look at Fox.”

It therefore combines many of Gillray’s favourite targets of satire: Royalty (at a time when it was still scandalous - and possibly seditious - to represent Royals in satirical print), hypocritical anti-establishment politicians, and the aura of supposedly grand surroundings, as they stagger out of Brooks’s in inebriation. Gillray has not yet perfected his trademark caricature of Fox, but Fox was such a gift to cartoonists that we would go on to see much, much more of him in Gillray’s work.

The inclusion of ‘Honest’ Sam House, ‘the republican publican’, described by Callum Smith as one of “the most frequently depicted members of the lower orders during the 1784 Westminster election” lends the trio a cross-class composition, representing upper, middle and lower classes - and casting doubt on the Prince of Wales’ company.

At this stage, Brooks’s was just a name in the title - there is no attempt to portray the Club itself, merely the idle, dissolute specimens being poured out of it after a long night.

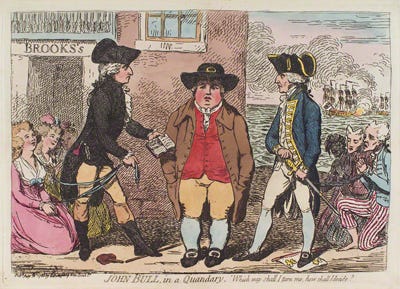

John Bull in a Quandary. Which way shall I turn me, how shall I decide? (31 July 1788)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The next example of a club in a Gillray print, John Bull in a Quandary (1788) - also of Brooks’s - is much more easily recognisably in Gillray’s style; but it is also a relatively rare print (so please excuse the small resolution of the above image). It is a more abstract image, showing an impossible scene, with the very-much-inland Brooks’s placed on the coast, so that we can view it alongside the burning galleon on the coast.

It is an ephereal picture, outlining John Bull’s dilemma. Jim Sherry’s analysis is thus:

“The choice of…Pitt and his Tory government [on the right] is Admiral Hood who is shown in naval uniform as if he was about to draw his sword in defence of his country, his foot trampling a French flag. Behind him are French sailors captured by Hood at the Battle of the Saints (shown in the background).

“Visually balanced against Hood is the Whig choice for Parliament, Lord John Townshend, the close friend of Charles James Fox. His conquests are not French sailors but young wives, for which (it is implied by the book in his hand) he is being prosecuted by their husbands for criminal conversation (Crim Con) to recover damages. His foot tramples a broken staff of liberty rather than a French flag. And in the background is not a battle from which he has emerged victorious but a gentleman's club, Brooks’s, known first and foremost for its gambling tables.”

The Club is therefore invoked as an idle and dissolute influence on a character identified with loose morals.

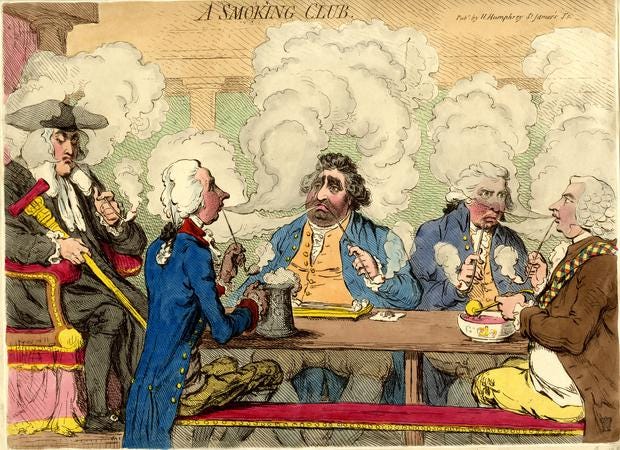

A Smoking Club (13 February 1793)

© Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

A Smoking Club (1793) sees us move from Gillray’s repeated abuse of Brooks’s, to offering up a parody that could be based on any number of clubs. The emphasis is on the casual mannerisms found in an informal club - but the setting is quite different. It is in the gallery of the House of Commons, with the suggestion that politics is starting to be conducted along the lines of a club.

On the nearby government bench are the Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger (left), and the Home Secretary, Henry Dundas (right). The further opposition bench has Charles James Fox (left) and the Whig MP-playwright, Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

The British Museum’s analysis notes:

“At the head of the table (left) in a raised arm-chair (in the manner of the chairman at a tavern-club) sits a man in the hat, wig, and gown of the Speaker (Addington) [Identified by Wright and Evans as Loughborough, ‘cogitating’ between the parties; this is inconsistent with the House of Commons setting and with Loughborough's appointment (26 Jan. 1793) as Chancellor.] holding the mace, which has been transformed into a crutch-like stick. He puffs smoke at both Treasury and Opposition benches. Pitt, on the Speaker's right, holds a frothing tankard inscribed 'G.R' and directs a cloud of smoke at Fox, who puffs back. Before Fox is a tray of pipes and a paper of tobacco, implying that he excels in abuse. On the extreme right Dundas, a plaid across his coat, puffs at the scowling Sheridan seated close to Fox; he has a punch-bowl inscribed 'G.R' in which he dips a ladle. Small puffs of smoke issue from the pipes, great clouds from the smokers' mouths…The House of Commons is burlesqued as a smoking-club, a plebeian gathering in which quarrelsome members were wont to puff smoke at each other”

The Clubs continue to be seen by Gillray as a bad influence, though this print showed more of a “both sides” approach, rather than simply berating Brooks’s and its influence on the Whigs.

Promis'd Horrors of the French invasion, or Forcible Reasons for Negotiating a Regicide Peace (20 October 1796)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion (1796) remains one of Gillray’s masterpieces; bold, crude, daring and ambitious - not to mention huge in scope, density and detail. By this stage, Gillray has gone beyond affectionate mockery of the Whigs with whom he had sympathised in his youth, and had fully gone down the safer route of becoming a propagandist for Pitt’s ministry. The print warns of the spirit of the French revolution spreading to Britain, projecting the Whigs as channeling a revolutionary spirit.

We see Pitt tied up at the pillory in the middle of St. James’s Street. (There was just such a structure on the street at the time, and club members looked out at the criminals being punished there.) A revolutionary red bonnet hangs atop the pillory, while Fox sadistically flagellates Pitt with some glee. There is some geographical flexibility, as Tory-identified White’s is moved half-way down the street so as to be placed directly opposite Whig-identified Brooks’s, and we can contrast the very different activities within them. The blood of the aristocracy is seen quite literally flowing down the open gutter at the centre of St. James’s Street. Whig peer Charles, 3rd Earl Stanhope, holds aloft a pole suspending the severed head and legs of Foreign Secretary Lord Grenville.

White’s on the left is being stormed by bayonet-wielding troops. Gillray, who often depicted John Bull, cogitated at length on the ways Britain was represented, and how it saw itself as being apart from France; one of the prime tropes used was in contrasting the large standing army found in France, which was seen as synonymous with despotism, with England’s post-Civil War distaste for large standing armies (which went hand-in-hand with identifying as a maritime power). The idea of soldiers storming White’s was therefore designed to trigger particular distaste, in what was supposed to be a bastion of calm. Reinforcing the idea is the way that members were shown being defenestrated from the balcony - including the Prince of Wales, and his younger brother Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. The corpses of other members are seen suspended from the light fitting in front of the Club, including Pitt acolytes George Canning and Lord Liverpool. Overturned gaming tables have been thrown out onto the road, with playing cards soaking in the blood running down the gutter.

Brooks’s on the right, by contrast, was depicted as both the architect and the beneficiary of this violence. A blood-drenched guillotine, of the type so identified with the excesses of the French Revolution, is seen having been erected on the balcony. Three decapitated heads are served up on a platter marked “Killed off for the public good” - those of former Home Secretary Viscount Sydney, Secretary at War (and leading anti-Jacobin) William Windham, and Master of the Rolls Lord Alvanley. Meanwhile, the Whig MP Thomas Erskine, popularly identified at the time with being defence counsel for the radicals in the “treason trials” two years earlier, is seen burning a copy of the Magna Carta while holding aloft a “New Code of Law.” An anthropomorphic bull, with its head a caricature of Whig peer Francis, 5th Duke of Bedford, is seen ramming and upending Edmund Burke, who drops two manuscripts marked Reflections Upon a Regicidal Practice, and Letters to the Duke of Bedford. Overflowing bags filled with looted cash are carried into the clubhouse, marked “Remains of the Treasury”, and “Requisitions from the Bank of England.”

St. James’s Palace, as a symbol of the monarchy at the end of St. James’s Street, can be seen in the distance having been set ablaze.

Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion stands as the only surviving print by Gillray to depict White’s. Unlike his great inspiration Hogarth, who over half a century earlier had rendered White’s as a thoroughly wicked place in A Rake’s Progress (1734), Gillray does not render it in entirely unflattering terms. True, it is a place of gambling excess, with its upended tables; but Gillray’s White’s is presented as a sympathetic victim, contrasted with an excess of wickedness emerging from Brooks’s.

The Feast of Reason, and the Flow of Soul,' - i.e. - the Wits of the Age, Setting the Table in a Roar (4 February 1797)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Altogether more gentle is the satire found in the following year’s The Feast of Reason, and the Flow of Soul (1797), which presents a more generic and intimate supper club. Jim Sherry’s description tells us:

“The Feast of Reason. . . shows five notable Whigs siting at a table engaged in what can only very broadly be described as conversation. They include (from left to right) George Hanger, the longtime carousing companion of the Prince of Wales, with spilled glass and his trademark bludgeon in his boot, Charles James Fox, the Whig opposition leader (with his back to us), Richard Brinsley Sheridan, playwright, ardent Whig, and perennial debtor, looking (as usual in Gillray's prints) furtive and unreliable, the diminutive Michael Angelo Taylor, Member of Parliament, Whig supporter, and frequent subject in Gillray's prints after 1793, and finally John Courtenay, a sarcastic speaker in Parliament, and member of both the Whig Club and Brooks's.

The full title of this print is "The Feast of Reason, & the Flow of Soul,"-i.e.-the Wits of the Age, Setting the Table in a Roar." The first part of the title alludes to lines from Pope, Imitations of Horace, II.1 and the second, to Hamlet, Act V, Scene 1. Both serve to contrast the sorry state of the present day (and the feeble offerings supposed to pass for wit) with a finer, richer past.

While the comedy here is aimed unambiguously at the Whigs, and so takes us into the realm of Brooks’s, the setting is less clear - it could even be in a private residence; but the atmosphere tallies with Gillray’s club dinners shown before and afterwards. The tone is more a lament than a condemnation.

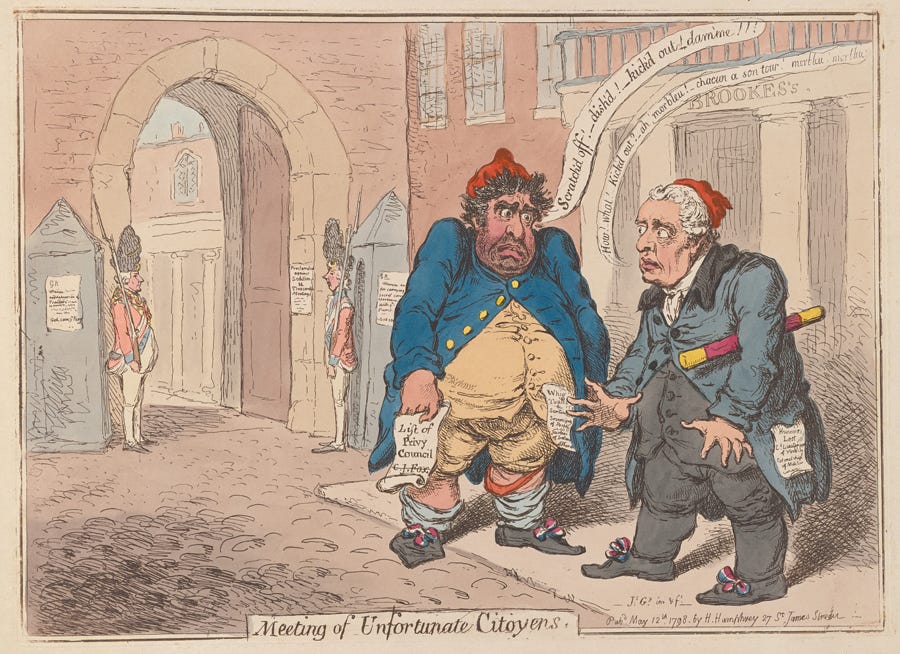

Meeting of Unfortunate Citoyens (12 May 1798)

© Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

The following year, Gillray returns to making Brooks’s a direct object of ire in Meeting of Unfortunate Citoyens (1798). It shows two of the most prominent Whigs, Charles James Fox and Charles, 11th Duke of Norfolk, deep in conversation outside of Brooks’s, ruing their marginalisation by the Crown, with St. James’s Palace visible behind them. Norfolk was recently disgraced, after having proposed a loyal toast - “Our sovereign’s health - the majesty of the people” - which was taken as an expression of republican sentinement. Gillray had already satirised this in The Loyal Toast (1798), but this print deals with the aftermath, and the cold shoulder of society. Jim Sherry’s commentary notes:

“Norfolk carries the baton of the hereditary Earl Marshal, a title and position which had belonged to the Dukes of Norfolk since the 17th century. Both are portrayed as (indeed they were) ardent supporters of the French Revolution. The title of the print itself describes them using the French term "Citoyens." Both wear a revolutionary bonnet rouge, both sport tri-color laces on their shoes, and Norfolk's speech is peppered with French phrases "ah! morbleu! - chacun a son tour!" Both express their surprise and chagrin ("Scratch'd off!- dishd! - kick'dout! - dam'me!!!") at being literally and figuratively marginalized by the King and his Tory ministers while Pitt and Dundas stand guard at the gate.”

Like some of Gillray’s previous prints, there is a little dramatic licence taken with dimensions and layout. The real St. James’s Palace is several hundred metres away, at the end of the street, whereas here it is rendered as adjoining, to drive the point home - Brooks’s, as their spiritual home is on the right, while the palace on the left is now out of bounds, protected by guards.

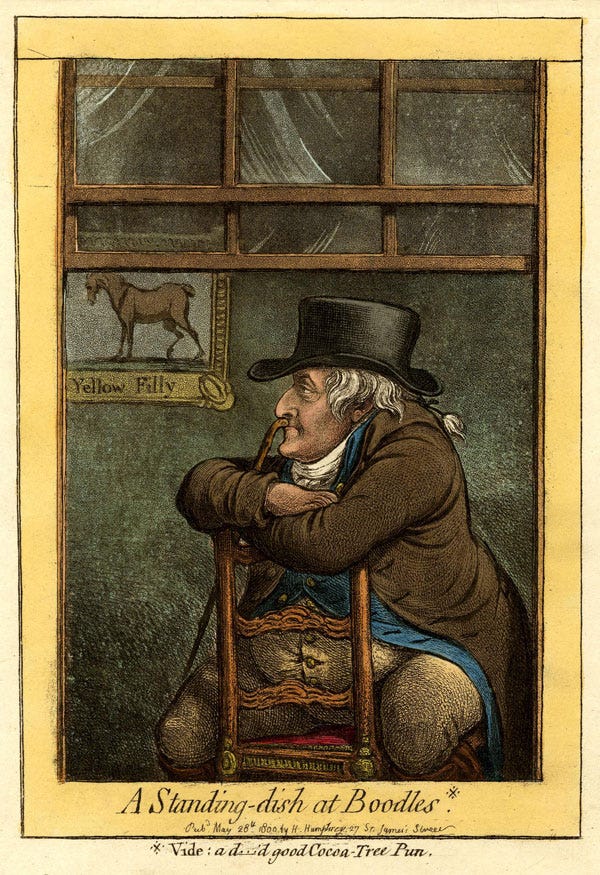

A Standing-dish at Boodles (28 May 1800)

© Trustees of the British Museum

A Standing-dish at Boodles (1800) remains, unsurprisingly, a favourite at Boodle’s to this day. It depicts the view through the window of Gillray’s next-door neighbours, Boodle’s, showing us Sir Frank Standish, 3rd baronet, in the Club. Sir Frank, an MP and keen gambler, was also staple of Clubland - he was a member of both Boodle’s and Brooks’s (and, as the above subtitle implies, most likely the Cocoa Tree Club), and he also frequented White’s. (He does not appear in the White’s membership rolls, but he made at least three appearances placing wagers in its betting book.) Gillray renders him as pensive and corpulent, with a plain interior for Boodle’s, and a background picture of Yellow Filly, the horse Sir Frank owned, which won the Epsom Oaks in 1786.

Jim Sherry highlights that Gillray’s framing is not an original composition; that it was copied - possibly as a commission - from a pre-existing portrait of Standish by another artist, which survives in the British Library; but that in comparing the two it is obvious that Gillray embellished the original image with a number of important flourishes (such as Standish’s cane) which may well have been gleaned from Gillray’s first-hand observations.

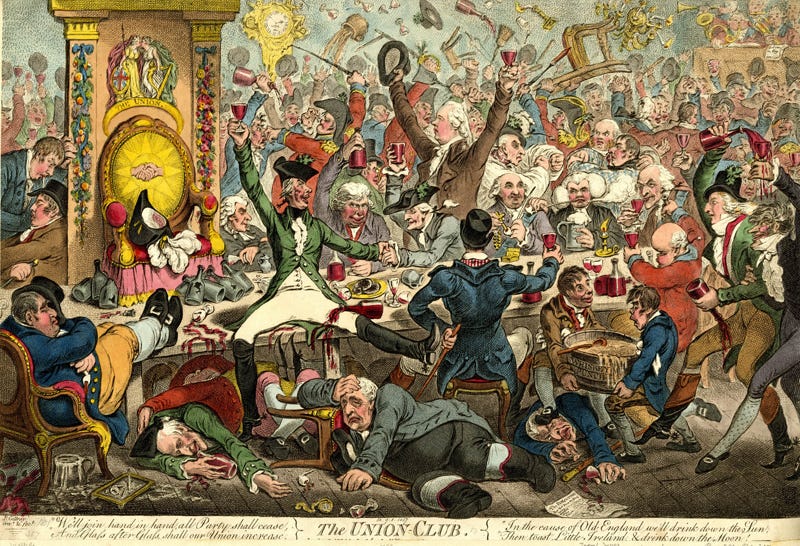

The Union Club (21 January 1801)

© Trustees of the British Museum

The following year’s The Union Club (1801) remains one of Gillray’s masterpieces. The Union of Great Britain and Ireland had been a heated topic of debate, and the recent passage of the Acts of Union 1800, which took effect on 1 January 1801, was marked by the Union Club, that had originally been formed in 1799 in anticipation of such a union. The Club was intended to celebrate the union of Britain and Ireland, and saw itself as a miniature parliament of all that was best in the United Kingdom.

This naturally lent itself to satire - and Gillray was neither the first nor the last engraver to satirisse this. An unknown artist had already published The Union Club some days before Gillray. And a couple of weeks after Gillray’s work, Isaac Cruikshank published The Breaking Up of the Union Club, and Charles Williams published The Union Club, both on 8 February 1801. (The image proved an enduring one, and even two decades later, Gillray’s print would itself be satirised in the notorious The New Union: Club, Being a Representation of what took place at a celebrated Dinner, given by a celebrated - society, published on 19 July 1819 by George Cruikshank, the son of Gillray’s friend and rival Isaac Cruikshank.)

The whole picture renders a very sceptical impression of the best that the United Kingdom has to offer. Vic Gatrell’s commentary notes:

“The Union Club is an elaborate comic fantasy on the debauchery of the Prince of Wales and his friends, the Foxite Whig grandees. In their newly-founded Union Club in Pall Mall, they and their hangers-on celebrate the queen’s birthday, presided over by the Prince of Wales.”

Passed out from a surfeit of alcohol under the table, his legs crossed, is the portly figure of the Prince of Wales. The central figure, raising a glass while knocking over a bottle of wine with his thigh, is Anglo-Irish peer Francis, 2nd Earl of Moira, a veteran of the American War of Independence portrayed with some irreverence. On the near side of the table (or underneath it) are Fox slumbering over discarded tankards; Charles, 3rd Earl Stanhope unconscious under the Prince of Wales; Charles, 11th Duke of Norfolk cradling his head; argumentative adventurer and naval captain Thomas, 2nd Baron Camelford with his back to us, a riding crop behind his back; and at the end of the table, the bulbous-headed Whig and racehorse enthusiast, Edward, 12th Earl of Derby. Entering the far-right of the frame are two fops drunkenly spilling wine, the Whig pro-Catholic Irish nobleman Colonel Montague James Mathew, and the playwright Sir Lumley Skeffington.

Left of the throne, from the bottom up, are Whig peer Francis, 5th Duke of Bedford, above him is Irish Whig MP George Tierney (who two years earlier had fought a duel with Pitt, after being accused of being unpatriotic), vomiting into Bedford’s hat; and there are three faded, phantom figures in the background. One of them is recognisably the late George, 3rd Earl of Orford - notorious in his lifetime for his reckless extravagance.

Right of the throne, sat along the table from left to right and all portrayed as drink-sodden, are Whig MP Thomas Erskine, radical Whig playwright and favourite Gillray subject Richard Brinsley Sheridan, keen horseracing enthusiast William, 1st Earl of Clermont shaking the Earl of Orford’s hand, former Whig Prime Minister (as the Earl of Shelburne) William, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne brandishing a rosary, former Whig pamphleteer Samuel Parr smoking a churchwarden pipe, and Scottish landowner and gambler William, 4th Duke of Queensberry. Behind them, standing triumphantly raising a glass in one hand and his hat in the other, is a drunken George, 4th Earl of Cholmondeley - a rare instance of a Tory peer being mocked in this picture.

In the background of the picture’s right are various fistfights. The one on the left is with Irish lawyer Sir Jonah Barrington, an avowed opponent of the Acts of Union, having his nose tweaked by army general and keen naturalist Thomas Davies. To the right of Cholmondeley, there is a fistfight between the Anglo-Irish peer George, 4th Baron Coleraine, a hanger-on of the Prince Regent’s, and Whig MP Charles Sturt. Sturt is being held back by fellow MP Thomas Tyrwhitt Jones.

Although this is supposed to be a cross-party gathering, and a number of non-aligned public figures are included, it is clear that (as with much of Gillray’s later art) Pitt’s Tories get off lightly. Instead, it is the Whigs, the army, and the Irish who bear the brunt of much of Gillray’s humour. The picture also bears comparison as much with Gillray’s often-chaotic renderings of the House of Commons, though with the pandemonium dialled up for the club setting. While the Union Club aimed to offer a new beginning, Gillray shows it to be a continuation of existing feuds and vices.

Anacreontick's in Full Song (1 December 1801)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

An altogether smaller scene is Gillray’s Anacreontick’s in Full Song (1801), from later that year. This homes in on the much more intimate real-life Anacreontick’s Society, a drinking and singing club with none of the pretensions and lofty goals of the Union Club.

It also offers us two lines of verse atop the piece:

“Whilst, snug in our Club-room, we jovially ‘twine —

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’ wine.”

Vic Gatrell’s commentary emphasis the bawdy innuendo and lustiness expressed in the songs sung in this kind of club. But Jim Sherry highlights a riddle - why this was printed in 1801, when Anacreontick’s had disbanded some years earlier. Sherry’s explanation is that this was possibly an unfinished plate from several years earlier, which Gillray decided to complete in 1801, a year when his output noticeably slowed compared to the preceding decade.

Unlike the preceding club cartoons based on Brooks’s, Boodle’s, White’s, or the Union Club, this does not portray recognisable well-known public figures. We must therefore infer either that the figures are sufficiently obscure as to have been lost to the mists of time; or else that Gillray chose archetypes, with wonderfully caricatured, expressive faces conveying the debauchery of the Club.

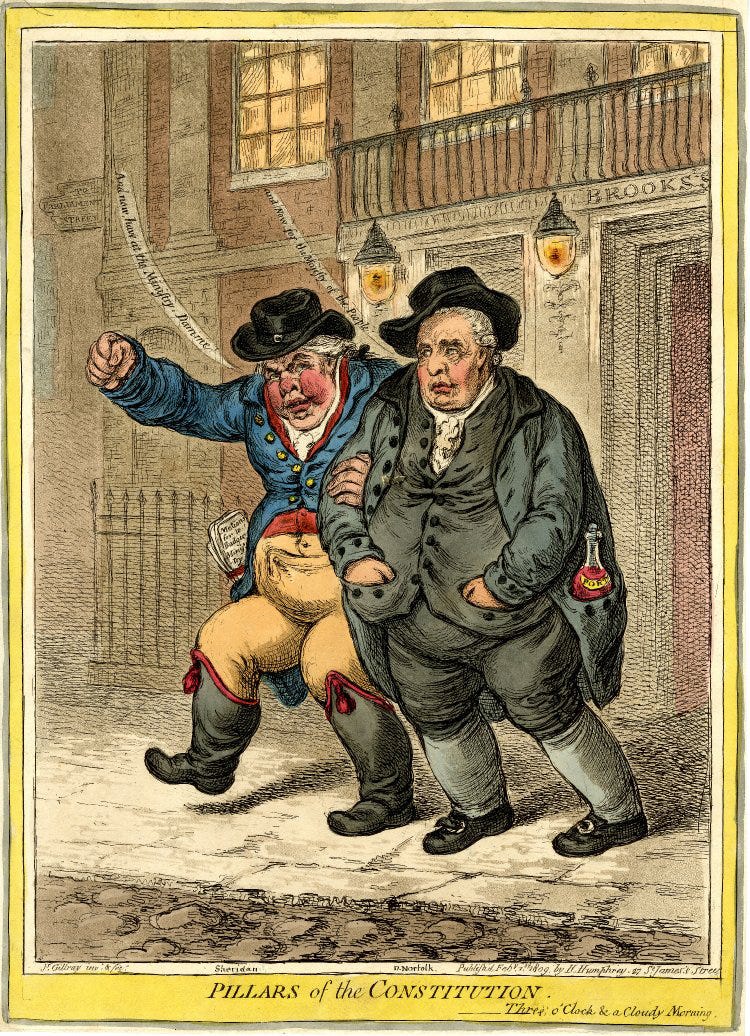

Pillars of the Constitution. Three o'Clock & a Cloudy Morning (1 February 1809)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Pillars of the Constitution (1809) is a wonderfully mature work - and no less scathing for its smaller scale. It portrays two old Gillray Whig favourites, playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan, and the 11th Duke of Norfolk, staggering drunkenly out of Brooks’s at three in the morning. The sign in the background “To Parliament Street”, suggests that fortified in the small hours, they intend to set off to a parliamentary debate during a late-night sitting. Sheridan, ever the eager scribe, has in his pocket a “Motion for badgering the ministry”, while proclaiming, “And now, hav at the miniftry, damme!”, while Norfolk has a full bottle of port in his pocket, and exclaims “And now for the Majesty of the People” - the latter a reference to his scandalous 1798 toast, alluded to above, seen as a declaration of republicanism.

What makes it a particularly damning - and knowing - portrait is the way that the Whigs mixed their business with pleasure, combining the serious (and in the eyes of the Tories, treasonable) conduct of public affairs with louche living.

Gillray’s health and eyesight were already rapidly failing by the time he etched this picture. He had been seriously ailing since at least 1807, and his periodic bouts of mania grew ever more frequent. By 1811, he would no longer be able to work. Pillars of the Constitution is therefore his last surviving print depicting clubs or the Clubland realm he lived around. In many ways, it is a fitting bookend to his earliest surviving Clubland portrait, Returning from Brooks’s (1784). Both prints have their emphasis on public figures rather than the Club, which is merely where the caricatures emerge - but which represents a baleful influence. Both prints focus on human foibles and hypocrisy. But the technique of Pillars of the Constitution is in another league from Returning from Brooks’s. The earlier work renders as a crude pastiche of the style of others. The later work shows a command of caricature, shading and framing, not to mention an eye for telling detail. It does not have the sweep of massive canvasses like Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion or The Union Club, but it does have the sharp focus of a master artist homing in on their theme.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: As can be inferred from the number of references to Jim Sherry above, I owe a particularly large debt and acknowledgement to his splendid Gillray website at https://www.james-gillray.org/, which remains the most comprehensive Gillray resource online. I have also used his dates for all prints, since some of Gillray’s publication dates are disputed.

Further reading

Esther Chadwick, The Radical Print: Art and Politics in Late Eighteenth Cnetury Britain (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2024).

Tim Clayton, James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2022).

Vic Gatrell, City of Laughter: Sex and Sature in Eighteenth-Century London (New York: Walker & Company, 2006).

M. Dorothy George, Hogarth to Cruikshank: Social Change in Graphic Satire (London: Allen Lane, 1967).

Richard Godfrey and Mark Hallett, James Gillray: The Art of Caricature (London: Tate Publishing, 2001).

Draper Hill, Mr. Gillray: The Caricaturist (London: Phaidon, 1965).

Alice Loxton, Uproar! Satire, Scandal & Printmakers in Georgian London (London: Icon Books, 2023).

Joseph Monteyne, Media Critique in the Age of Gillray: Scratches, Scraps, and Spectres (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022).

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.

Thanks very much for sharing this post - I very much look forward to reading more of of these in the future.

Interestingly, or possibly not, the two lines quoted from the Song of the Anacreontic Society were sung to a tune by John Stafford Smith, which, with new lyrics by Francis Scott Key, was in 1931 adopted as the official national anthem of the United States ‘the Star Spangled Banner’.