Clubs in popular culture: Blades in Ian Fleming's James Bond novels

A deep dive into a fictional club

Blades as eventually seen onscreen, in Die Another Day (2002), using the Reform Club as a filming location.

In the film Die Another Day (2002) - not well-regarded as a James Bond film, or as a film - we finally get to see a version of Blades onscreen. Yet what we see in that movie, a fencing-themed club filmed at the Reform Club and in studio sets designed in a matching style, scarcely tallies with what we have been led to expect. The club recurs through six of Ian Fleming’s original Bond novels. Save for one detail, it is a mostly-consistent world, in a fantasy club. This article looks at Fleming’s world-building around Blades.

For most of his adult life, including the entirety of his time writing Bond books, Fleming was a club member. He had joined White’s in 1936 - the oldest club in London - but subsequently resigned, complaining “they gas too much”, which would not have been desirable for someone working in Naval Intelligence. He joined Boodle’s on 6 January 1942, it being the second-oldest club in London, which was then (as now) characterised by a strong dose of country aristocracy and squirearchy. Boodle’s remained “much-used” by the author until his death in 1964. Although there are elements of both clubs in the literary Blades, it is clearly intended to be an entirely original, fictitious club - albeit one whose details heavily lean on Boodle’s.

The Club makes its deput appearance in the third James Bond novel, Moonraker (1955), where it receives its fullest description, and features heavily in the early part of the plot. After that, it is not mentioned again until the seventh book, Goldfinger (1959), and it has further passing mentions in Thunderball (1961) and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963), before being briefly seen again as a setting for short scenes in the final two Bond novels, You Only Live Twice (1964) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1965). Unless otherwise stated, all quotations are from the Club’s first and fullest appearance, in Moonraker (1955).

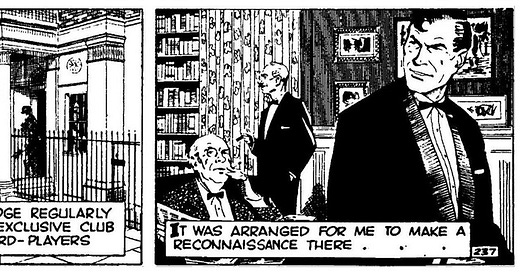

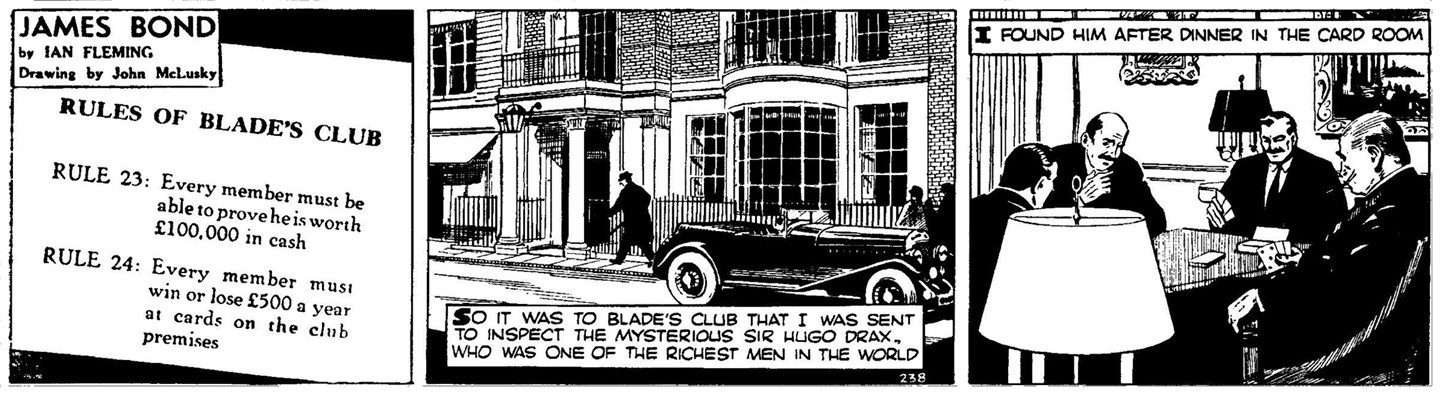

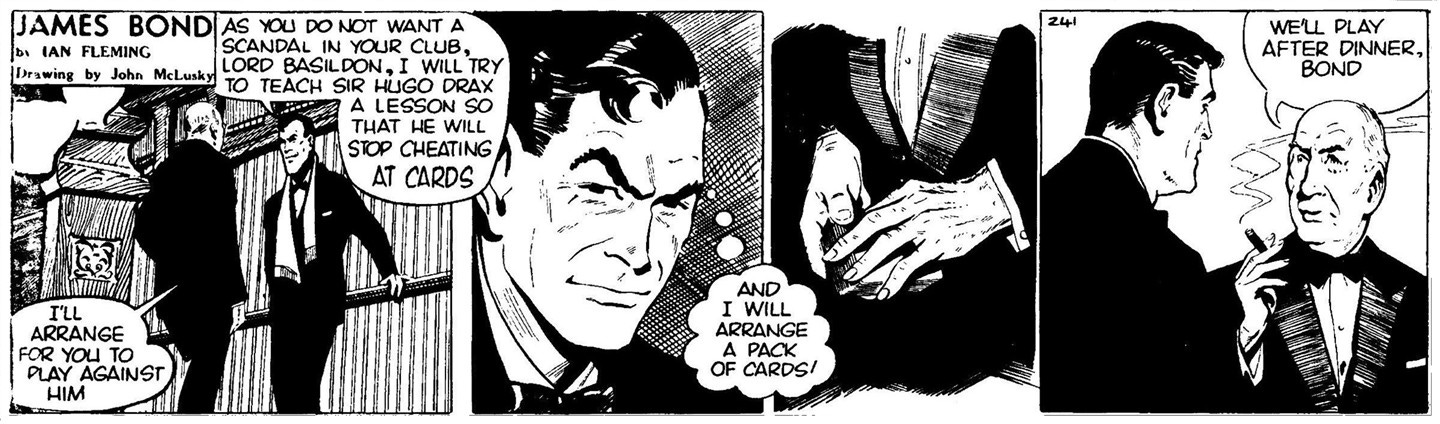

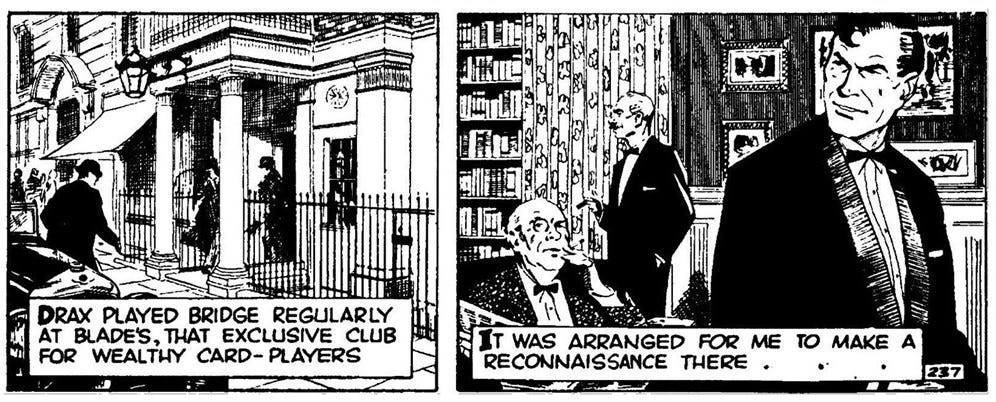

Blades, as portrayed in the 1959 Daily Express comic strip of Moonraker - an adaptation which was, for the most part, very faithful to the original novel. (Although the spelling was changed to Blade’s.) Note the use of the exterior of Boodle’s as the model for Blades.

Culture

Fleming fleshes out the Club’s idiosyncratic and distinctive character. It is described as:

Blades, probably the most famous private card club in the world.

and Fleming notes that it:

remains to this day the home of some of the highest 'polite' gambling in the world.

Card-themed clubs were highly fashionable, for a variety of reasons. There had long been a tradition of London clubs specifically dedicated to playing cards, such as the Baldwin Club on Pall Mall and then Bolton Street, the Portland Club then located on Charles Street, and the revived Crockford’s on Carlton House Terrace. Indeed, the earliest Georgian-era clubs such as White’s, Boodle’s and Brooks’s had all made their reputation on the back of prolific gambling, and each continues to hold and display early gambling counters as museum pieces. And the Turf Club, despite being subsequently renamed over its equestrian connections, started out as the Arlington Club, where the rules of whist were first developed. Gambling on games of chance continued to be very chic in the 1950s, and notionally illegal, lending a frisson to card games, which maintained the alibi of being games of skill, although also having the strong dose of chance which made them so unpredictable. The Betting and Gaming Act 1960 would liberalise these laws, paving the way for chic new 1960s clubs such as the Clermont on Berkeley Square and Quent’s on Hill Street. But until then, the safest refuge for gamblers was behind the respectability of old, established Georgian clubs.

The card room, as seen in the 1959 Daily Express comic strip of Moonraker.

Membership at Blades costs an annual subscription of £50, plus a one-off entrance fee of £100 in 1955 - worth approximately £1,100 and £2,200 in today’s money, making it about half the subscription of today’s London clubs (though with a comparable joining fee), but broadly average for the clubs of mid-20th century London. Indeed, there was rarely any corelation between the prestige of a club and its subscription, and many of the most openly elitist clubs could be relatively inexpensive compared to their for-profit peers.

The composition of the Club is described thus:

The membership is restricted to two hundred and each candidate must have two qualifications for election; he must behave like a gentleman and he must be able to 'show' £100,000 in cash or gilt-edged securities.

This is consistent with many traditional London clubs being cashless, though depending on the solvency of their members to meet regular, monthly accounts billed.

The emphasis on behaviour is a very Victorian concept, since the earlier Georgian clubs tended not to set any rules for behaviour; and the 19th century saw a major evolution in the concept of “gentlemanliness”, which is found in increasingly elaborate behavioural rules upheld by a Committee.

Fleming’s description goes on:

The amenities of Blades, apart from the gambling, are so desirable that the Committee has had to rule that every member is required to win or lose £500 a year on the club premises, or pay an annual fine of £250. The food and wine are the best in London and no bills are presented, the cost of all meals being deducted at the end of each week pro rata from the profits of the winners. Seeing that about £5,000 changes hands each week at the tables the impost is not too painful and the losers have the satisfaction of saving something from the wreck; and the custom explains the fairness of the levy on infrequent gamblers.

In other words, each year members are expected to gamble at least £11,000 in today’s money, or face a fine of some £5,500.

The “amenities” themselves are surprisingly unelaborated upon, beyond food and wine. There is mention of:

a front hall

a staircase

a card room

a dining room

12 bedrooms

lavatories

what presumably sounds like a drawing room

3 bow windows - whose position seems to shift (more on that later…)

Yet beyond that, we hear of nothing else. It should be noted that unlike later 20th century clubhouses such as the RAC and the Lansdowne, the aristocratic 18th century clubs did not (and do not) possess facilities such as gyms, swimming pools, squash courts and Turkish baths. Even a library, as found at Brooks’s, was a relative rarity, which was without a counterpart in clubs like Boodle’s, Pratt’s and White’s.

In keeping with the older clubs, the drawing room is non-smoking, with members having to move to the card room to smoke. We later learn, in You Only Live Twice (1964), that the Club continues to vend new Cuban cigars, long after the Cuban embargo.

However, the Club appears to be remarkably flexible in catering to the whims of its members. Porterfield, the head steward, notes:

“You know that terrible stuff Sir Miles [Messervy - aka M] always drinks? That Algerian red wine that the wine committee won't even allow on the wine list. They only have it in the club to please Sir Miles.”

Four members of staff are named in the books: Brevett, the porter; Porterfield, a veteran who served with M in the navy and who was the Club’s head steward; Tanner, a waiter; and Lily, the headwaitress, described in The Man with the Golden Gun as “a handsome, much-loved ornament of the club.” Of the staff more generally, Fleming has this to say:

Club servants are the making or breaking of any club and the servants of Blades have no equal. The half-dozen waitresses in the dining-room are of such a high standard of beauty that some of the younger members have been known to smuggle them undetected into débutante balls, and if, at night, one or other of the girls is persuaded to stray into one of the twelve members' bedrooms at the back of the club, that is regarded as the members' private concern.

This passage reads as a testosterone-fuelled fantasy by Fleming, which he later elaborates upon:

Bond's eyes followed the white bow at [the waitresses’] waist and the starched collar and cuffs of her uniform as she went down the long room. His eyes narrowed. He recalled a pre-war establishment in Paris where the girls were dressed with the same exciting severity. Until they turned round and showed their backs. He smiled to himself. The Marthe Richards law [which outlawed prostitution in France] had changed all that.

In reality, the 1950s age profile of club servants, male and female, tended strongly towards those who had been born in the 19th century. Yet the presence of female servants was not unusual by the 1950s - indeed, it was very much the norm, even in London’s men-only clubs. Throughout two world wars with conscription, a shortage of manpower had led many, if not most, London clubs to rely on a great many female staff.

Other traditions of club life were noticeable:

Only brand-new currency notes and silver are paid out on the premises and, if a member is staying overnight, his notes and small change are taken away by the valet who brings the early morning tea and The Times and are replaced with new money. No newspaper comes to the reading room before it has been ironed.

This has contributed to a long-standing myth that such a practice is (or even was) commonplace in Clubland, whereas it in fact mirrored a practice which by the 1950s was only found at Boodle’s and a handful of other clubs, and which had already died out by the 1960s.

Fleming’s detail that:

Floris provides the soaps and lotions in the lavatories and bedrooms; there is a direct wire to Ladbroke's from the porter's lodge

should be read in the context of the writer’s penchant for lovingly detailing individual brands of luxury goods throughout his work - or rather, goods which seemed like luxuries in the 1950s, such as Bond’s glow-in-the-dark Radium wristwatch from Rolex, and his polyester shirts.

In You Only Live Twice (1964), we are told that:

Exactly one month before, it had been the eve of the annual closing of Blades. On the next day, September 1st, those members who were still unfashionably in London would have to pig it for a month at White’s or Boodle's. White’s they considered noisy and "smart," Boodle's too full of superannuated country squires who would be talking of nothing but the opening of the partridge season. For Blades, it was one month in the wilderness. But there it was. The staff, one supposed, had to have their holiday. More important, there was some painting to be done and there was dry-rot in the roof.

This reference to the annual summer closure for staff holidays and repairs is lightly fictionalised. The annual closure is more typically timed in the month of August. The comments about White’s and Boodle’s read as Fleming’s own catty observations on his ex-club and his current club.

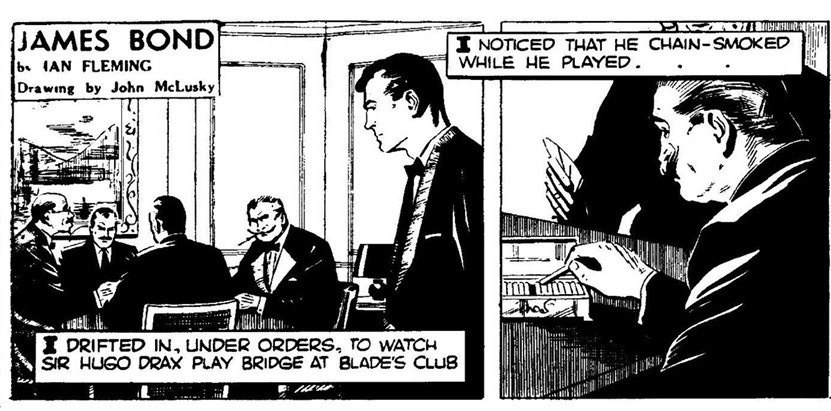

A later appearance of Blades, in the 1966 Daily Express comic strip adaptation of The Man with the Golden Gun.

Members

We meet a handful of the Club’s 200 members. It is unlikely that M is a typical member (how many serving heads of the British secret service are there?); yet broadly, the membership seems to be a cross-section of the British Establishment of the 1950s, including a smattering of peers, financiers and eminent medical doctors. The Chairman is identified as Lord Basildon, whom Fleming describes as “stuffy.”

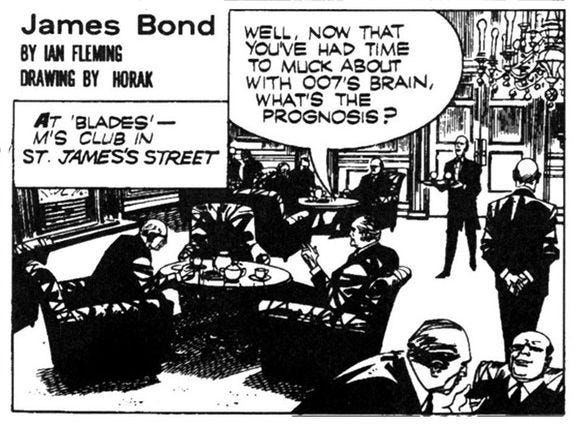

The Club’s Chairman, Lord Basildon, as portrayed in the 1959 Daily Express comic strip.

It is clearly a rich person’s club. Aside from the high minimum spend at the card tables, M tells Bond as his guest to not worry about ordering the most expensive dishes on the menu:

“One of the first rules of the club, and one of the best, was that any member may speak for any dish, cheap or dear, but he must pay for it. The same's true today, only the odds are one doesn't have to pay for it. Just order what you feel like.”

Despite it being a cards club, the members are of distinctly mixed ability at the card tables. M believes:

“They're a mixed lot of players. Some of them are the best in England, but others are terribly wild. Don't seem to mind how much they lose. General Bealey, just behind us, doesn't know the reds from the blacks. Nearly always a few hundred down at the end of the week. Doesn't seem to care. Bad heart. No dependants. Stacks of money from jute. But Duff Sutherland, the scruffy-looking chap next to the chairman, is an absolute killer. Makes a regular ten thousand a year out of the club. Nice chap. Wonderful card manners. Used to play chess for England.”

If we take at face value Fleming’s observation that £5,000 a week changes hands at the Club’s gaming tables, and calculate an average of £25 per member per week (based on 200 members), then we can observe that Duff Sutherland makes an average of nearly eight times this amount, every week. (£192 a week x 52 weeks = £10,000 a year.) Yet Sutherland is far from the biggest card player in the Club, and it is noted that members:

win or lose, in great comfort, anything up to £20,000 a year.

which would equate to some £440,000 today.

Nonetheless, despite the mixed abilities of the players, gambling provides a theme which binds this club together - something clear from Fleming’s description:

There were perhaps fifty men in the room, the majority in dinner jackets, all at ease with themselves and their surroundings, all stimulated by the peerless food and drink, all animated by a common interest--the prospect of high gambling, the grand slam, the ace pot, the key-throw in a 64 game at backgammon. There might be cheats or possible cheats amongst them, men who beat their wives, men with perverse instincts, greedy men, cowardly men, lying men; but the elegance of the room invested each one with a kind of aristocracy.

Such a description does not paint the members of Blades in the most flattering light, suggesting that away from the building’s calming influence, they are anything but remarkable or admirable. Meanwhile, Fleming’s reference elsewhere to “younger members” suggests that Blades was not exclusively the preserve of the retired and elderly.

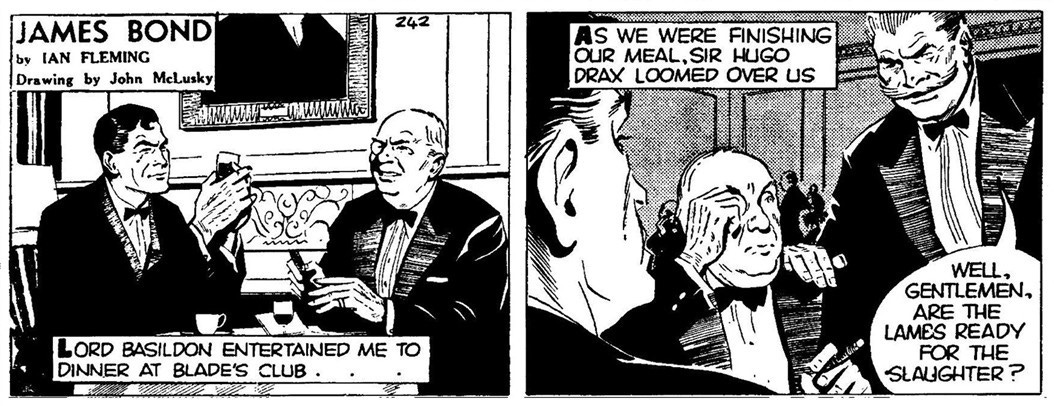

Lord Basildon and James Bond dine at Blades, when Hugo Drax approaches, in the Daily Express adaptation of Moonraker (1959).

It is a surprisingly unsociable club, with the members heavily engrossed in their card games. The very first mention of the Club is when M says of Bond villain Hugo Drax:

“He's a member of Blades. I've often played cards with him and talked to him afterwards at dinner.”

But M also admits that he barely knows Drax - conversation, presumably, revolving around play. And for such a supposedly illustrious club, it contains a surprising concentration of outright megalomaniacs among its 200 members; in Goldfinger, M remarks of the title villain:

“Goldfinger. Odd chap. Seen him once or twice at Blades. He plays bridge there when he's in England.”

and Bond later reflects that the unscrupulous Goldfinger is a:

“respected member of Blades, of the Royal St Marks [Golf Club] at Sandwich.”

Hugo Drax holds his fellow members in contempt, telling Bond:

“Those bloody fools in Blades for instance. Moneyed oafs. For months I took thousands of pounds off them, swindled them right under their noses until you came along and upset the apple-cart.”

Indeed, for all its luxury, Fleming sometimes paints Blades as a stale establishment, with Bond in The Man with the Golden Gun dreading:

A grisly reunion [for retired secret service veterans] held in the banqueting hall at Blades…[with] a lot of people who had been brave and resourceful in their day but now had old men's and old women's diseases and talked about dusty triumphs and tragedies.

Matters at Blades are handled informally. Although Drax’s cheating at cards had long been widely suspected, the Club sought to avoid a confrontation and possible litigation, and instead dealt with the matter through the Chairman, Lord Basildon, enlisting M’s informal advice.

Part of the Club’s own rulebook is routinely ignored. Fleming notes:

Mention of Hazard perhaps provides a clue to the club's prosperity. Permission to play this dangerous but popular game must have been given by the Committee in contravention of its own rules which laid down that 'No game is to be admitted to the House of the Society but Chess, Whist, Picket, Cribbage, Quadrille, Ombre and Tredville'.

Nonetheless, the Club prizes its reputation, like many others - making it a natural scene for drama. According to M, the Chairman believes:

“You couldn't stop a scandal like that getting out. A lot of MPs are members and it would soon get talked about in the Lobby. Then the gossip-writers would get hold of it. Drax would have to resign from Blades and the next thing there'd be a libel action brought in his defence by one of his friends. Tranby Croft all over again.”

The novel also captures a particular moment in time when dress codes were indeterminate:

“Don't bother about dressing. Some of us do for dinner and some of us don't.”

Formally codified dress codes had only been introduced in the London clubs for the first time in the late 1940s (starting with Brooks’s) and through the 1950s. Moonraker, published in 1955, and touching on Fleming’s memories of Clubland before this, captures an era of Clubland in transition. It is also noticeable that by the time of the 1959 Daily Express comic strip adaptation, members are all donning dinner jackets when dining.

Some of the members are health freaks. In the third appearance of Blades, in Thunderball (1961), Miss Moneypenny recounts how one of the members is an habitué of the Shrublands health farm:

“M got lumbago and some friend of his at Blades, one of the fat, drinking ones I suppose, told him about this place in the country. This man swore by it…He said it only cost twenty guineas a week which was less than what he spent in Blades in one day and it made him feel wonderful.”

It is left ambiguous by Fleming whether Bond himself eventually joins Blades. In Moonraker, his status is clearly that of M’s guest, and Fleming notes that he has “only” played cards at Blades a dozen times up to that point, while the porter “knew Bond as an occasional guest.” Fleming notes that Bond, “Doesn't look the sort of chap one usually sees in Blades.” By the time of the eleventh Bond book, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963):

Bond was cursing the prospect before him and wishing he was playing a tough game of bridge for high stakes at Blades

It is unclear from this description whether he would have been a member by this time, or would have continued to gamble as M’s guest. For someone on a civil service salary - even paid danger money - it would have been quite an extravagance.

Food

The food at Blades seems distinctly more elaborate than at other London clubs of the era, when stodge was common. Wartime food rationing had only ended in 1953. Nonetheless, the emphasis is on traditional dishes, as at many of these clubs.

In Moonraker, M orders Highland-cured smoked salmon to start, followed by devilled kidney and bacon with peas and new potatoes, and a dessert of strawberries in kirsch, followed by the club delicacy of marrow bone. Bond also has the smoked salmon starter, followed by lamb cutlets with the same vegetables as M, and a slice of pineapple for dessert. After a vodka (“pre-war Wolfschmidt from Riga”) with the starter, M drinks claret (Mouton Rothschild '34), whilst Bond drinks champagne (Dom Perignon ‘46, with the wine waiter noting how scarce this is in 1950s London), all washed down with coffee and club brandy (“from one of the Rothschild estates at Cognac”).

The Club also maintains a cold buffet table, presumably for members dining in a hurry:

laden with lobsters, pies, joints and delicacies in aspic.

History

Fleming presents us with a potted history of the Club, clearly based upon Boodle’s in many of its details.

The exact date of the foundation of Blades is uncertain. The second half of the eighteenth century saw the opening of many coffee houses and gaming rooms, and premises and proprietors shifted often with changing fashions and fortunes. White's was founded in 1755, Almack's in 1764, and Brooks's in 1774, and it was in that year that the Scavoir Vivre, which was to be the cradle of Blades, opened its doors on to Park Street, a quiet backwater off St James's. The Scavoir Vivre was too exclusive to live and it blackballed itself to death within a year.

Fleming’s dates and names are slightly off, though are in keeping with some of the dates which were then in circulation among Clubland’s strong oral tradition, where precise dates and chronologies became muddled after retelling over long lunches. White’s had opened as a hot chocolate shop in 1693 (with an informal club around the back), and was reconstituted as a club in 1736. There had been two neighbouring Almack’s clubs on Pall Mall - one (which became Boodle’s) founded in 1762, the other (which became Brooks’s) founded in 1764.

When Boodle’s moved from Pall Mall to St. James’s Street in 1783, it took over the clubhouse that had been built for the short-lived Savoir Vivre Club (which was commonly spelt Sçavoir Vivre in the post-war years - see Anthony Lejeune’s book on Clubland). This had existed from 1775 to 1782.

Fleming continues his history of the Club:

Then, in 1776, Horace Walpole wrote: 'A new club is opened off St James's Street that piques itself in surpassing all its predecessors' and in 1778 'Blades' first occurs in a letter from Gibbon, the historian, who coupled it with the name of its founder, a German called Longchamp at that time conducting the Jockey Club at Newmarket.

From the outset Blades seems to have been a success, and in 1782 we find the Duke of Wirtemberg writing excitedly home to his younger brother: 'This is indeed the "Ace of Clubs"! There have been four or five quinze tables going in the room at the same time, with whist and piquet, after which a full Hazard table. I have known two at the same time. Two chests each containing 4000 guinea rouleaus were scarce sufficient for the night's circulation.'

Fleming made the observation:

It is not as aristocratic as it was, the redistribution of wealth has seen to that, but it is still the most exclusive club in London.

which feels like a comment on Boodle’s in the 1950s. During Churchill’s first visit to Boodle’s in 1954, it had been observed that as well as comprising “decent country gentlemen”, half the members present were stockbrokers.

Other details are shared with Clubland more broadly, such as when Bond:

remembered the story of how, at one election, nine blackballs had been found in the box when there were only eight members of the committee present. Brevett, who had handed the box from member to member, was said to have confessed to the Chairman that he was so afraid the candidate would be elected that he had put in a blackball himself. No one had objected. The committee would rather have lost its chairman than the porter whose family had held the same post at Blades for a hundred years.

This is a well-worn Clubland tale, told of many clubs, with many variations. (Indeed, I referred to it in my last book.) It is clear that the names and places drew extensively on similarities with Boodle’s - but as we shall see, it was sufficiently different to not be a straightforward renaming.

Inconsistency

Fleming sometimes contradicts himself across the books. In You Only Live Twice, he writes that:

M…rarely used Blades, and then only to entertain important guests. He was not a "clubable" man, and if he had had the choice, he would have stuck to The Senior [the United Service Club on Pall Mall - the building now being the Institute of Directors], that greatest of all Services' clubs in the world. But too many people knew him there, and there was too much "shop" talked. And there were too many former shipmates who would come up and ask him what he had been doing with himself since he retired. And the lie, "Got a job with some people called Universal Exports," bored him, and, though verifiable, had its risks.

There is reason to mistrust the description of M as seldom using his club. Later in the same chapter, the leading English neurologist Sir James Molony has this to say to M, about the latter’s habit of using the Club to draw on his professional expertise for secret service matters:

“My friend, like everybody else, you have certain patterns of behaviour. One of them consists of occasionally asking me to lunch at Blades, stuffing me like a Strasbourg goose, and then letting me in on some ghastly secret and asking me to help you with it. The last time, as I recall, you wanted to find out if I could extract certain information from a foreign diplomat by getting him under deep hypnosis without his knowledge. You said it was a last resort. I said I couldn't help you. Two weeks later, I read in the paper that this same diplomat had come to a fatal end by experimenting with the force of gravity from a tenth floor window. The coroner gave an open verdict of the 'fell or was pushed' variety. What song am I to sing for my supper this time? Come on, M.! Get it off your chest!”

M making extensive use of the Club is also confirmed by his having a regular ritual, described in The Man with the Golden Gun (1965):

At Blades, M. ate his usual meagre luncheon--a grilled Dover sole followed by the ripest spoonful he could gouge from the club Stilton. And as usual he sat by himself in one of the window seats and barricaded himself behind The Times, occasionally turning a page to demonstrate that he was reading it, which, in fact, he wasn't.

Location

The entrance to Boodle’s on St. James’s Street, used as the model for the entrance to Blades in the 1959 Daily Express comic strip of Moonraker.

The location and layout of Blades is left slightly ambiguous. Some believe that it was a simple transposition - Stephen R. Hill, in his history of Boodle’s, writes, “Fleming placed scenes in Boodle’s in an unconvincing attempt at anonymity, for the detail is so exact.” But I am unconvinced - too many of the details don’t quite tally. The initial description is as follows:

Bond left the Bentley outside Brooks's and walked round the corner into Park Street.

It is often inferred from this that Blades must be on the site of Pratt’s, off St. James’s Street, facing Brooks’s; though it should be pointed out that this is on Park Place. There is no “Park Street” in the St. James’s area, and it is not entirely clear if this is simply a renaming of Park Place, or a fictitious street of its own. That this was not a mistake or misprint is confirmed by a subsequent description, when Bond:

drove to St James's Street. He parked under cover of the central row of taxis outside Boodle's and settled himself behind an evening paper over which he could keep his eyes on a section of Drax's Mercedes which he was relieved to see standing in Park Street, unattended.

The mention of Boodle’s as a separate club also confirms that Blades is not simply meant to be Boodle’s under a pseudonym, but is intended to be a different club altogether.

Fleming’s initial description also mentions:

The Adam frontage of Blades, recessed a yard or so back from its neighbours, was elegant in the soft dusk.

The reference to an Adam building is intriguing. Robert Adam, whilst a highly influential Georgian architect, never designed any clubhouses. The Boodle’s clubhouse has long been commonly misattributed to Adam (including in Fleming’s own lifetime); but it was in fact the work of John Crunden, a keen disciple of Adam’s, who designed the building in the Adam style.

Fleming’s initial description continues:

The dark red curtains had been drawn across the ground floor bow-windows on either side of the entrance and a uniformed servant showed for a moment as he drew them across the three windows of the floor above. In the centre of the three, Bond could see the heads and shoulders of two men bent over a game, probably backgammon he thought, and he caught a glimpse of the spangled fire of one of the three great chandeliers that illuminate the famous gambling room.

The bow-window has long been a feature of Clubland architecture (and literature). The Boodle’s clubhouse was the first to have a bow-window, in its original 1770s incarnation as the Savoir Vivre Club. This was emulated by White’s in an 1811 rebuild, which added their own bow-window. However, no London clubhouse has ever conformed to Fleming’s description of having multiple bow windows. Some clubs have had bay windows - but these are of later Victorian architecture.

The exterior of Boodle’s. Note the bay window in the centre of the ground floor; and the configuration of “three windows” on the first floor (and indeed the ground floor).

There is clearly a superficial likeness to Boodle’s in having three windows on the first floor - although note that none of these first-floor windows is a bow window. But Fleming’s Blades Club seems to be a souped-up double-fronted clubhouse with the entrance in the centre, and a bow window on either side, giving it at least two.

There is a fuller description of the interior:

Bond pushed through the swing doors and walked up to the old-fashioned porter's lodge ruled over by Brevett, the guardian of Blades and the counsellor and family friend of half the members….

Bond followed the uniformed page boy across the worn black and white marble floor of the hall and up the wide staircase with its fine mahogany balustrade…The page pushed open one wing of the tall doors at the top of the stairs and held it for Bond to go through. The long room was not crowded and Bond saw M. sitting by himself playing patience in the alcove formed by the left hand of the three bow windows. He dismissed the page and walked across the heavy carpet, noticing the rich background smell of cigar-smoke, the quiet voices that came from the three tables of bridge, and the sharp rattle of dice across an unseen backgammon board.

Now we have it established that there are three bow windows on the first floor. This would be a gargantuan clubhouse, much bigger than Boodle’s. Additionally, in You Only Live Twice (1964), we are told that the Club has:

the bow-window looking out over St. James's Street

This may simply mean the bow window closest to the junction with St James’s Street, from which the best view of it can be obtained - this would make the most sense if the building is located on the site of Pratt’s. Yet if taken literally, it would mean one bow-window is a side window of the building, overlooking St. James’s Street - considerably changing the architecture already described. It could also indicate a fourth bow window on the side of the building, since Moonraker had previously unambiguously established that there were three bow windows on the first floor. That’s a lot of bow windows.

There are other hints that this is not simply a renamed Boodle’s, in the fuller description:

Bond followed M. through the tall doors, across the well of the staircase from the card room, that opened into the beautiful white and gold Regency dining-room of Blades…he walked firmly across the room to the end one of a row of six smaller tables, waved Bond into the comfortable armed chair that faced outwards into the room, and himself took the one on Bond's left so that his back was to the company.

The colour scheme does not match the contemporary blue-and-white colour scheme of Boodle’s in the 1950s and 1960s. Nor does it match the red trim of White’s at the time. It is clearly intended to be different.

The first-floor Saloon of Boodle’s, pictured in Fleming’s lifetime, with contemporary decoration and colour scheme. (Photo credit: frontispiece of Roger Fulford, Boodle's, 1762-1962: A Short History (London: Boodle's, 1962).)

The main drawing room is described as having three paintings: a Beau Brummel portrait by [Thomas] Lawrence, an unfinished full-length portrait of Mrs Fitzherbert by [George] Romney, and [Jean-Honoré] Fragonard’s painting of Jeu de Cartes. As this post points out, these appear to be fictional paintings by real-life artists, of real-life subjects. George “"Beau” Brummel had been a member of White’s before his exile, while Maria Fitzherbert was the future George IV’s long-standing mistress. Fleming’s description continues:

Along the lateral walls, in the centre of each gilt-edged panel, was one of the rare engravings of the Hell-Fire Club in which each figure is shown making a minute gesture of scatological or magical significance. Above, marrying the walls into the ceiling, ran a frieze in plaster relief of carved urns and swags interrupted at intervals by the capitals of the fluted pilasters which framed the windows and the tall double doors, the latter delicately carved with a design showing the Tudor Rose interwoven with a ribbon effect.

The central chandelier, a cascade of crystal ropes terminating in a broad basket of strung quartz, sparkled warmly above the white damask tablecloths and George IV silver. Below, in the centre of each table, branched candlesticks distributed the golden light of three candles, each surmounted by a red silk shade, so that the faces of the diners shone with a convivial warmth which glossed over the occasional chill of an eye or cruel twist of a mouth.

These details suggest a club somewhat more ostentatious than any real-life London club of the 1950s, with Fleming’s imagination embellishing the luxuries of Clubland.

Fleming also notes:

the club has the finest tents and boxes at the principal race-meetings, at Lords, Henley, and Wimbledon, and members travelling abroad have automatic membership of the leading club in every foreign capital.

This tallies with several socially well-connected clubs of the day - including Boodle’s, Buck’s, the Cavalry Club, the Garrick Club, the Guards Club, the United Service Club and White’s - maintaining tents at Ascot. But as with Fleming’s descriptions of Blades, he seems to have exaggerated the scope and scale of events covered. In reality, as the memoir of a contemporary Club Secretary makes clear, the annual Ascot tent was very enjoyable, but also expensive and destabilising for a club, requiring much of the staff to relocate for the week, effectively necessitating a club closure. Fleming’s suggestion of three extra sporting events triggering club closure are of doubtful practicality - particularly as the Lord’s cricket fixtures last for much of the summer.

All in all, it is clear that Fleming does not offer up a simple renaming of Boodle’s, but a wholly original, fictitious club which does not fully tally with the details of any known club - yet which is still heavily influenced by Boodle’s more than any other club, and in which his imagination runs riot.

I really don't understand how a club limited to 200 members could survive financially. More on club finances please.