Clubs in Film: 'The Man Who Never Was' (1956)

This is a spotlight on a highly unusual appearance of a club in a film - for several different reasons. The Man Who Never Was (1956), based on Ewen Montagu’s 1953 book of the same name, tells the real-life story of ‘Operation Mincemeat’, an elaborate plot to distract the Nazis in World War II. Ahead of the widely-anticipated Allied invasion of Sicily, the British had arranged for the corpse of a fake naval intelligence officer (“Major Martin”) to be washed up off the coast of Spain. The attaché case handcuffed to the body was filled with forged documents that suggested the Allies were about to invade Greece - and found its way to German intelligence

The front lobby of the Naval and Military Club, as seen in The Man Who Never Was (1956).

The last third of the film centres around an Irish spy, Patrick O’Reilly, working for the Germans. He tries to establish whether the fictional “Major William Martin” ever existed. And he does this by making enquiries at Martin’s lodgings, tailor, bank - and club.

What makes the depiction of the Naval and Military Club remarkable is that the Club was used as a filming location, doubling for itself. I believe it may be the first time that film cameras were allowed on the premises of a London club. Although London club exteriors can often be seen in streetscapes, and it was not unusual for newsreel crews to film people entering and leaving, or for clubs to take still photographs of empty clubrooms, it was very rare before the 1960s to see film footage of a club interior.

We see firstly the driveway of the Naval and Military Club’s home at 94 Piccadilly, the building where it was based from 1865 to 1999. Visible from inside the yard are the famous gateposts marked “In” and “Out” which give the club its famous sobriquet - although those markings are not visible from the inside.

In most respects, the scene is played out with great accuracy. There are army and navy officers milling about. The porter is expected to know the names of every member; but as was the case in a services club during wartime, when a great many new temporary officers had recently joined, he openly admits that he cannot remember everybody’s name, and needs to refer to the list. (“Well, if he’s a temporary, I probably shouldn’t know him, sir. There’s a lot of members now that I don’t know.”) The porter’s lodge looks fully authentic, complete with overflowing parcels awaiting collection by members, and the nearby baize-green noticeboard.

Of course, even with the real-life Naval and Military Club used as a filming location in 1955, there is still one major inaccuracy which crept in. In 1940, the front of the clubhouse had suffered visible bomb damage during the Blitz, which was not fully repaired until after the war. The scenes shot in front and inside in 1955, by contrast, look deceptively prisitine.

This is despite the bombing having been referred to by the porter: “What with the bomb damage and no staff, we’re a bit behind with things these days.” Nevertheless, the exterior and front lobby look rather tidier than might have been expected in 1943.

The Naval and Military Club’s front entrance, seen in the film, has no sign of bomb damage.

Although the entire “Patrick O’Reilly” sequence was facribated for the film, the inclusion of the Naval and Military Club is faithful to Montagu’s original 1953 book, which records that the Club was central to the deception. Montagu noted that the fictional Major, “could have been staying at a Service club while in London, so he might have a receipted bill for the last part of his stay there.” Accordingly:

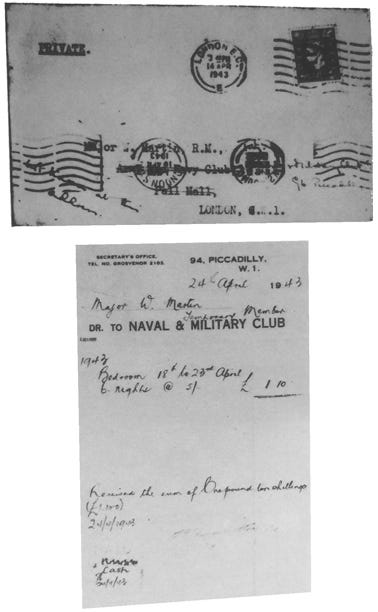

“One of us had got the co‑operation of the Naval and Military Club; we had been given a bill dated the 24th April which showed that Major Martin had been a temporary member of that club and had stayed there for the nights of the 18th to 23rd April inclusive; apart from its other purpose of general build‑up of the Major's personality, it afforded a strong indication that he was still in London on the 24th.”

To lend further verisimilitude to the deception, British intelligence forged a letter to “Major Martin” from his bank manager, expressing concern about the size of his overdraft, and addressed to him at the Naval and Military Club:

“It had been arranged that this letter from the bank should be sent through the post to Major Martin at the Naval and Military Club, but it was erroneously posted addressed to him at the Army and Navy Club, Pall Mall; there the Hall Porter marked the envoy "Not known at this address" and added "Try Naval and p79 Military Club, 94 Piccadilly." This seemed to us to be a most convincing indication that the letter was real and not specially prepared, so we decided that Major Martin should keep this letter in its envelope.”

The forged bill for Major Martin, and the envelope for the bank manager’s letter, erroneously sent to the Army and Navy Club on Pall Mall, and then forwarded to the Naval and Military Club on Piccadilly.

There is one other glimpse of Clubland afforded in the film. When the character of Patrick O’Reilly makes a call from a phone box, he does so from the south-east corner of St. James’s Square, with the north side of Pall Mall. The view behind him is of the south side of Pall Mall. The building on the left, behind the phone box, is immediately recognisable as the Reform Club. But the building on the right-hand side is the bombed-out rubble remaining from the Carlton Club.

While the Carlton Club was bombed in 1940, the bombsite was not actually sold or redeveloped until 1955 - the Carlton still had hopes for nearly 15 years after the bombing of rebuilding its previous clubhouse, and retained ownership of the land during that time. (It was not unusual for bomb craters and bombsites to persist on prime real estate for so long after the war: the final episode of The Prisoner, from 1968, shows a bombsite still present in the north-west corner of Trafalgar Square.) Accordingly, when The Man Who Never Was came to be filmed in 1955, the bombsite of the former Carlton Club was just one of many London bombsites still in place.

This makes the film an authentic and fascinating document of Clubland in the 1950s, in its capturing the old “In and Out Club” building, in its recording its real-life role in a now-famous deception, and in offering rare colour footage of the Carlton Club bombsite.

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.