Clubs in Film: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943)

A deep dive (in more ways than one) into the Royal Bathers Club

The films of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger have had a very welcome recent revival in interest, thanks in part to David Hinton’s new documentary Made in England, with Martin Scorsese exploring his lifelong passion for the work of ‘The Archers’.

Clubs recur throughout Powell & Pressburger’s work, starting with their second film, Contraband (1940) - where the Army & Navy Club is the butt of recurring jokes. Both Powell & Pressburger were long-time members of the Savile Club (which still displays their BAFTA Lifetime Achievement Award in its dining room), in Mayfair. Clubland suited ‘The Archers’, with their fantastical tales wrapped up in genteel English whimsy.

This post looks at the fictional Royal Bathers Club on Piccadilly, which is the club of the title character in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). It offers a particularly vivid insight into club life at its peak in the 1900s, and in slightly diminished circumstances during World War II, with its blackouts and bomb precautions and food rationing. It also becomes his home, after the main character’s London townhouse with a lifetime of possessions is bombed out, and he moves into his club.

A scene near the end of the film, amid the bombed-out rubble of the main character’s home in the 1940s, with a sign showing that he is now lodging at his club.

The Royal Bathers Club

In the film, we see three parts of the Royal Bathers Club: the exterior, the front hall, and the Turkish baths in the basement. Despite relatively little screen time, the baths are central to the plot (providing the film’s main framing device), and Powell & Pressburger give us plenty of world-building, as we see the Club in both 1902 and 1943. Its address is given as Piccadilly. The street of Piccadilly itself housed some two-dozen clubs at the time, while the streets immediately north of Piccadilly hosted nearly 50 clubs.

The relatively unusual "Royal” prefix in the name clearly suggests royal patronage - though this would simply have meant that at one stage, a senior member of the Royal family had been a member, and was willing to grant their formal patronage to the endeavour. Membership of clubs by Royals is not, in itself, that unusual; but use of the “Royal” prefix is. (Other examples today include the Royal Automobile Club, Royal Ocean Racing Club, Royal Over-Seas League and Royal Thames Yacht Club, as well as former clubhouses such as those of the Royal Aero Club, Royal Anglo-Belgian Club, Royal Cruising Club, and Royal London Yacht Club; and last year, King Charles III agreed to allow the Kennel Club to become the Royal Kennel Club on reaching their 150th anniversary.)

A painting of a military battle occupies pride of place in the Royal Bathers Club’s front hall, in both 1902 and 1943.

The Club depicted is clearly popular with army officers, from young subalterns to major-generals. And the painting of a battle in the front hall suggests a strong military connection. Even the staff are shown as displaying a military background. The front hall is more formal - Clive Wynne-Candy (the “Colonel Blimp” of the title) addresses the man at the front desk as “Porter”, whereas a few moments earlier, he had addressed the bathroom attendant as “"Peters”, clearly knowing him by name. It is possible that the Club had its roots as a military club, before its most distinguishing feature - the Turkish baths which give it is name - led it to being opened up to civilian members as well. This would explain the strong military theme.

Even in its Edwardian heyday, the Club is portrayed as being an uneasy contrast between boisterous younger members carousing through the premises with song, and ageing members who prefer a quiet nap.

Military-themed clubs were some of the earliest non-aristocratic clubs of 19th century London. These included the Guards Club, founded in 1810; the United Service Club (aka “The Senior”, for senior army & navy officers) which existed from 1815-1975; its offshoot the Junior United Service Club from 1827-1967; the Army & Navy Club founded in 1836, and its two offshoot Junior Army & Navy Clubs (one in 1871-1904, the other from 1910-70); and the Naval & Military Club founded in 1862, and its offshoot Junior Naval & Military Club which operated from 1870-1939. The strong pre-existing officers’ mess culture of these establishments led them to heavily influence our idea of how a “typical” club would feel; their combination of tradition, discipline and informality contrasted with the more dilettante-based feel of aristocratic clubs in the 18th century.

Interior - Front Hall

The front hall of the Royal Bathers Club, while filmed in a studio, is a good approximation of the archetypal London club of the 1940s. As mentioned, the room is dominated by a military painting, depicting a battle. There is a grand staircase with ornate bannisters, seen in profile. Staple pieces of Clubland furniture can be seen, including the porter’s desk (unchanged in four decades), and the green baize noticeboards for club notices.

The front hall of the Royal Bathers Club in the 1940s, complete with the glass sign pointing visitors to the Turkish baths downstairs.

Most of the fixtures and fittings of the front hall are identical in the 1900s and 1940s, including the desk, painting, notice board and chandelier. Minor differences include the desk lighting (a gas lamp in 1902, a shaded electrical lamp in 1943), and the 1940s presence of masking tape on the windows and propaganda posters through the lobby. The biggest difference is in signage - the 1902 front hall has no signage directing people downstairs, whereas the 1940s front hall has a hanging glass sign declaring “TURKISH BATHS DOWNSTAIRS” - perhaps a sign that the 1940s seemed a more vulgar age, in keeping with one of the film’s main themes.

Interestingly, the club porters’ livery is more elaborate in 1943 than in 1902. The earlier setting shows a porter in a plain black tailcoat with black epaulettes; whereas the 1940s setting shows a more heavily emroidered tailcoat, with red highlights and brass buttons, in a neo-Georgian style. This suggests a certain amount of invented tradition in the intervening forty years.

The 1900s and 1940s Royal Bathers Club’s porters’ livery, seen side by side, on the left of each frame.

Interior - Turkish Baths

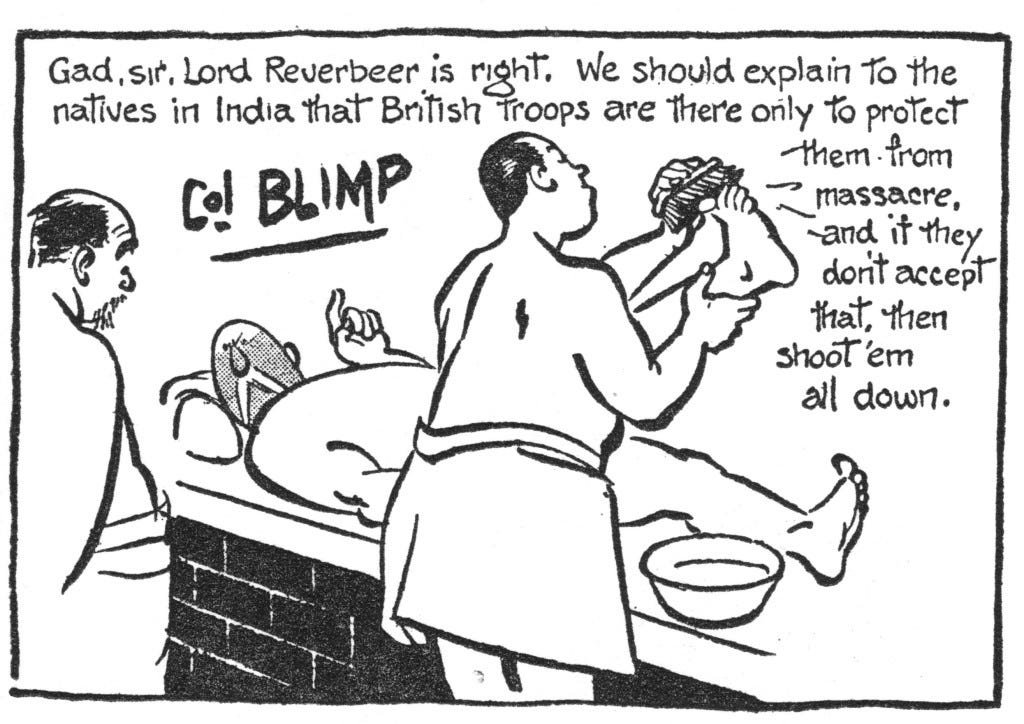

David Low’s original cartoon character of the boorish Colonel Blimp was rarely seen outside of a Turkish bath - and for the film, centring Blimp’s own fictional club around the pursuit of bathing made perfect narrative sense.

Colonel Blimp, as originally portrayed by cartoonist David Low, perenially barking out reactionary comments in a Turkish bath.

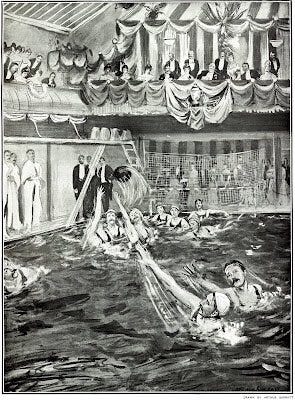

One might be forgiven for thinking that Mayfair’s highly fashionable Bath Club, founded in 1894, had been a model for the Royal Bathers Club, if only for the name. But there are several reasons why this would not have been the case. Firstly, the Royal Bathers Club appears to be a men-only club - Blimp’s ATS driver Angela “Johnny” Cannon is able to visit the Club as a guest, but she is visibly the only woman on the premises, with several dozen members in sight; whereas the real-life Bath Club was a mixed-sex club (with separate ladies’ entrance on Berkeley Street and gentlemen’s entrance on Dover Street, but mixed-sex use of the baths). Secondly, the Bath Club had suffered a direct hit from bombing in 1941, and was without premises of its own at the time of filming, in the summer of 1942. And finally, the “baths” of the Bath Club referred to swimming baths - that club’s Turkish bath offering was a relatively minor afterthought, unlike the palatial baths seen in the Royal Bathers Club.

The swimming baths of the Bath Club, on Dover Street, in the 1930s.

Indeed, private members’ clubs containing Turkish baths were still a relative rarity. More common was the practice of members availing themselves of Turkish baths near to their club, as with the two Turkish baths on Jermyn Street which were popular with members of the St. James’s clubs, and the baths on Northumberland Avenue which were frequented by members of the clubs around Whitehall.

The late-Victorian boom in Turkish baths is subject of Malcolm Schifrin’s excellent Victorian Turkish Baths (2015), which traces their origins in Ireland, introduction to England via Manchester and Liverpool, and eventual spread to the south of England. Schifrin’s book even has a whole chapter dedicated to the pruvate members’ clubs which housed Turkish baths. But they were a relative rarity. Today, of the dozens of Victorian Turkish baths, only half a dozen survive - and two of them are still contained in private members’ clubs (the Royal Automobile Club in London, and the Western Baths Club in Glasgow).

The plunge pool in the Turkish baths of the Royal Automobile Club. (Photo credit: RAC website.)

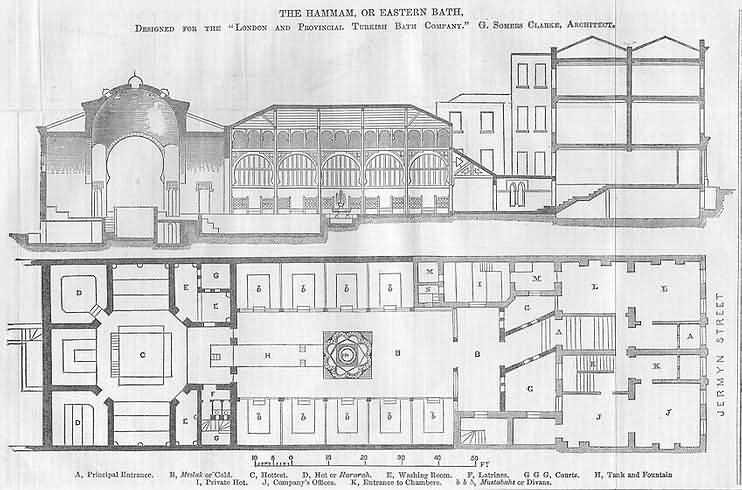

While there is some superficial resemblance between the Royal Bathers Club plunge pool and that found in the Royal Automobile Club (above), Schifrin pointed out to me a few years ago that a much likelier candidate for the model is the Jermyn Street Hammam, which was popular with much of Clubland.

The Jermyn Street Hammam, which opened in the 1850s. (Photo credit: Malcolm Schifrin.)

If we compare the surviving photographs and floorplan of the Jermyn Street Hammam, then it becomes clear how closely the film’s Turkish baths set is modelled upon it; simplified, certainly, but nevertheless retaining a great many period details, as well as the broad layout.

Plan of the Jermyn Street Hammam. (Picture credit: Malcolm Schifrin.)

As can be seen, the Royal Bathers Club set was divided into four segments, which broadly followed the Jermyn Street Hammam layout.

The basement lobby of the Turkish baths in the Royal Bathers Club.

Firstly, there was a lobby, reached down some stairs. While these stairs are not diagonal as with the Jermyn Street Hammam, the characters running down from offstage to screen left gives a suggestion of turning a corner. The lobby itself is decorated very appropriately: Moorish arches, mosaic tiling, elaborate rugs, a locker-room, and a reception desk staffed by a fez-wearing attendant. A particularly nice touch is the pair of decorative statue-lamps by the stairs, which echo a common trend in Victorian clubs; similar decorative lamps can still be seen today on the main staircase of the Oxford & Cambridge Club.

The main staircase of the Oxford & Cambridge Club today, lined with Victorian statue-lamps. (Photo credit: Oxford & Cambridge Club website.)

Swinging open the main doors, with frosted glass, we can see the remainder of the baths set split into three more areas. While the whole area is never seen in one shot, we can assemble montages from some of the tracking shots. Firstly, there is this outer plunge pool area, complete with curtained-off changing cubicles and doors either side of a decorative arch, all echoing the Jermyn Street Hammam’s layout.

Composite of the outer plunge pool area seen in the film.

Beyond the doorway is the second half of the plunge pool, a much warmer area, in close proximity to the frosted glass which separates off the Turkish bath.

The doorway in the middle, opened, leading from the outer plunge pool to the inner plunge pool, by the Turkish bath.

Finally, we see the Turkish bath itself. In keeping with the film’s whole framing device, what is seen here is highly unflattering - a group of bloated, elderly members snoozing away, baffled by the intrusion of the outside world. The “Blimp” character, dozing on a slab of marble, is almost served up like a sacrificial offering.

The Turkish bath seen in the film, with Clive Wynne-Candy - the “Colonel Blimp” of the film - seen asleep in the centre.

The flashback to the 1900s - as the title character lashes out at the impudent young member of the Home Guard, and they brawl in the plunge pool, with “Blimp” emerging 40 years younger - gives an idea of the Turkish bath in its Edwardian heyday.

The film suggests that even in these halcyon Edwardian years, when Clive Wynne-Candy was a young man, the baths were already frequented by crusty old generals, harrumphing at the antics of subalterns.

Exterior

I have saved the exterior of the Royal Bathers Club for last, because it poses the biggest mystery. What we see is a working club exterior across two time periods. It is highly accurate, with many of the Victorian clubhouse conventions: a raised ground floor, surrounding trench (for access to servant areas below which are illuminated), tall arched windows, gas lamps with elaborate metalwork, and a neoclassical façade with a portico. But I am still baffled by where it was filmed. It is most likely the exterior of a real-life club, long since extinct.

We see more of the building exterior in the 1902 flashback scenes. This is particularly the case when Wynne-Candy and Hopwell cross the street to buy chestnuts from a street-seller, and the camera briefly pulls back to show more of the frontage, including the top of the portico, and the suggestion of a first floor.

Of today’s surviving historic club buildings, the clubhouse exterior most resembled is the Oxford & Cambridge Club, but the building is clearly different, and both real and fictional clubs reflect the neoclassical trend of many Victorian London clubhouses.

The exterior of the Oxford & Cambridge Club today. (Photo credit: CAMRA website.)

When we see the exterior of the fictional Royal Bathers Club in the 1940s, the building is mostly obscured by sandbag barricades and masking tape over the windows (a standard precaution to minimise the risk of shattering during bombings), as well as a brick wall erected in front of the main entrance.

The club in the “present day”, in 1943, is seen covered in sandbags and masking tape.

The fictional location of the Royal Bathers Club.

We are offered a mostly-consistent location for the Royal Bathers Club, not only through being told it is on Piccadilly, but in two car journeys seen in the film, shot across real-life locations around Mayfair. It is worth dissecting these.

Firstly, there is the film’s opening chase scene, where Wynne-Candy’s ATS driver Cannon is rushing to warn him at the club, while her Home Guard boyfriend Lt. “Spud” Wilson is following her and attempting to outrun her, to ambush Wynne-Candy.

The same view 70 years apart, from the western end of Upper Grosvenor Street, looking north-west towards the junction with Park Lane. On the left, in the film as shot in 1942, and on the right, on Google Street View, photographed in 2012. The corner building no longer has blinds, and is painted a paler shade of white, but is otherwise unchanged. Note the sign in the right-hand picture, directing passers-by to the real-life Dominion Officers’ Club.

Wilson says “I know a couple of short cuts after Marble Arch” (and the trucks are seen heading south down Park Lane, from Marble Arch), although this is partly contradicated by what happens next. The camera is located on the corner of Upper Grosvenor Street, towards Hyde Park, and shows the trucks continuing south along Park Lane. Since the next exterior shot is one block directly east of this, on the south side of Grosvenor Square, we have to assume that the trucks continued at least one block further south, before doubling back up north into Grosvenor Square, and then heading east. Perhaps there was an obstruction along the way.

46 Grosvenor Street, which housed the wartime Dominion Officers’ Club, referenced in the sign seen in the movie. (Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.)

Incidentally, the film’s view of Upper Grosvenor Street at the time captured a street sign pointing east, towards the “Dominion Officers’ Club.” This was a real-life wartime establishment at 46 Grosvenor Street, near the entrance into Grosvenor Square, which offered membership and hospitality to visiting officers of Commonwealth armed forces. The presence of this club in this location - and others like it - might also explain why Lt. Wilson is so familiar with the street layout and traffic patterns of the area.

The same view 80 years apart, from the south-east corner of Grosvenor Square, looking east towards Grosvenor Street. On the right-hand side is the corner of Mount Street, where both vehicles turn. On the left, in the film as shot in 1942, and on the right, on Google Street View, photographed in 2022.

The next exterior shot is far more logical. Wilson spots Cannon’s car in the south-east corner of Grosvenor Square, and takes a right turn into Mount Street, heading south. The view is easy to identify - it remains almost identical today.

Two views of Berkeley Square, over 80 years apart. The top-left, in the film, shows the north-eastern corner looking eastwards, with North Bruton Mews in the background. The top-right shows the same view in 2024. The bottom-right is looking southwards down the square from the north-eastern corner, towards the corner with Bruton Street. The bottom-right shows the same view in 2024. Note that both 1930s tower blocks on the east side of the square, recently completed when the film was shot in 1942, still stand today.

There is then a slight edit, because the next exterior shot shown two seconds later shows us the north-east corner of Berkeley Square, with both vehicles circulating clockwise - even though it would take a good 30 seconds to drive there from Grosvenor Square. Cannon’s car heads off left from the Square, eastwards down Bruton Street, while Wilson’s truck continues down south. He insists that he knows a short-cut to get there quicker then Cannon, telling his driver, “Keep right on his [the taxi in front’s] tail. Don’t follow her [Cannon], keep straight on. Second left.”

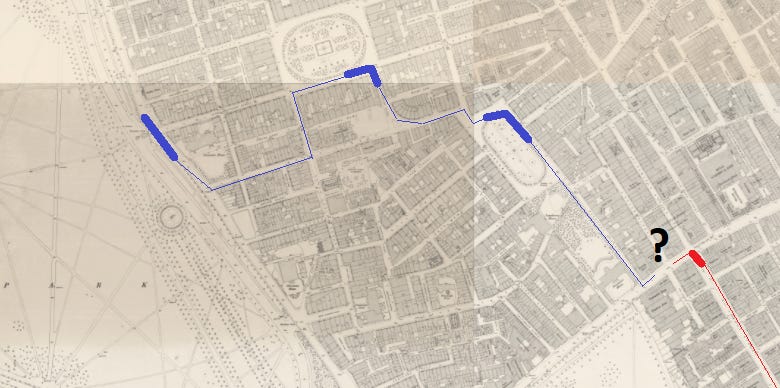

Heading straight on south from Berkeley Square after Bruton Street, the second left would indeed be Piccadilly. You can see Wilson’s route sketched out in blue on the map below - with the confirmed sightings shown on film in a thick blue line, and the presumed remainder of the journey in a thin blue line. [I have used an 1890s Ordnance Survey Map as the base map, as although it does not perfectly match with 1942 - serious inter-war work had been done to the south-west of Berkeley Square by then - it gives a much more accurate rendering of the route than a modern map, which would give an incorrect number of turnings due to post-war redevelopment of the area.]

Wilson’s comments about a short cut are consistent with the area around Berkeley Square having been notorious for traffic congestion in the 1930s, which was the reason given by the Metropolitan Borough of Westminster having extensively reworked the south-west corner of the square a decade earlier, including the demolition of half of Lansdowne House to create Fitzmaurice Place, improving traffic access to the square (and incidentally creating the Lansdowne Club in the process).

Route showing the two car journeys seen in the film. The blue line is Lt. Wilson’s truck headed to the club, with actual sightings in a thick line, and the presumed remainder of the route in a thin line. The red is Gen. Wynne-Candy’s car journey from the club. The question mark shows the approximate location of the Royal Bathers Club, somewhere along the north side of Piccadilly, between Berkeley Street and Albemarle Street.

The map also records in red a much shorter, second car journey, undertaken by Wynne-Candy later in the film, as he is driven off from his club to a meeting. His car starts heading east along Piccadilly, and is seen taking a right turn, going south down St. James’s Street, with back-projection filling out the rest of the street, including turning the corner at St. James’s Palace.

Incidentally, the location filming offers a brief, split-second glimpse of White’s, in the summer of 1942.

White’s club, seen on the right in the background as General Wynne-Candy’s car drives by, in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), filmed in the summer of 1942.

The locations shown onscreen suggest the Club could only have been located on a relatively small stretch of the north side of Piccadily, along the two blocks between Berkeley Street and Albemarle Street, accounting for numbers 63 to 73 Piccadilly. There had once been a real-life club along that very stretch: the mixed-sex Grosvenor Club, located at number 68A from 1897 until 1911, when it moved to Buckingham Palace Road. However, no known clubhouse matches the club design seen. And at the time of the film’s setting, there were no clubs located on that exact stretch, even though there were dozens nearby.

Indeed, if we consider Cannon’s car pulling up outside the Club heading from left to right, then it is likely that the Club is located on an even narrower stretch, between Dover Street and Albany Street, assuming her car had driven down Dover Street.

The most likely locations of the Royal Bathers Club, marked in red on the north side of Piccadilly, with the right-hand block more likely.

Locating the real-life location used for the Royal Bathers Club

I have been unable to definitively prove where the exterior of the Royal Bathers Club was filmed. But I am convinced that it was a real building exterior, and not a film set.

There are numerous reasons for thinking that the exterior cannot have been a set, for the detailing would have been far too extravagant for something only glimpsed in passing: visibly thick Victorian glass, period Victorian light fittings, period detail to both the building itself and its neighbours, including a basement and first floor. And if we’d only seen pillars, then that might have been a component of a studio set without a top, but the camera does briefly pull back to reveal a full portico. Finally, the detail which I think is too elaborate to ignore is the presence of actors inside the building, visible to the audience through the windows. Building a clubhouse façade is one thing, but constructing an elevated interior with actors moving around and internal furnishings is one step too far for anything but the real article.

Michael Powell himself gave contradictory accounts of the location. For his 1988 director’s commentary on the film (originally recorded for the LaserDisc edition, and now supplied with the BluRay), he initially says, “This is at Marble Arch, in London, shot on location. I don’t think you see the arch, the park’s just around the corner.” However, it doesn’t seem to match the style of any of the buildings around Marble Arch. Later, Powell says of the same club exterior, “This actually was in Berkeley Square.” What is clear is that location filming for the movie happened in both Marble Arch and Berkeley Square - but that neither was necessarily the location of the club exterior. (One scene shot on location visibly shows the address of 139 Park Lane, which is directly opposite Marble Arch, while a scene described above shows Berkeley Square itself.)

Powell’s alternative suggestion of Berkeley Square makes little sense. Much of the west and north of the square survives intact from the 18th and 19th centuries, but none of those buildings look anything like the clubhouse exterior seen. Much of the east side was taken up with two inter-war office blocks, both of which can briefly be seen in the film itself, and which remain today. The south side, taken up with part of Lansdowne House prior to its demolition in the early 1930s, was taken up with a 1930s apartment block by the time of filming (now long since demolished), which did not resemble the Victorian neoclassical clubhouse.

There is another clue that the filming was not done on Berkeley Square. A brief, one-second shot from a high angle opposite shows Home Guard soldiers flooding out of their truck in front of the club. It is unlikely to have been filmed in Berkeley Square, as there was no existing structure in the square at this height and angle from which this could have been photographed. Nor would it have been worth the time and expense of constructing a raised platform for such a split-second establishing shot. Instead, it was clearly filmed from across the street - most likely somewhere nearby. Which suggests that it was filmed on a street, not a garden square.

The street would most likely have been somewhere relatively easy to cut off from traffic for the purposes of filming - no extraneous traffic passes by during the 1940s scenes (in contrast to the location filming on Park Lane and St. James’s Street, the latter even featuring a passing pedestrian curiously staring into the camera); while the 1900s scenes show contemporary hansom cabs and early motor cars passing in a choreographed pattern. Given the heavy traffic of Piccadilly in 1942, we can almost certainly rule out Piccadilly as a location.

Addendum

As mentioned, Powell & Pressburger were keen, long-time members of the Savile Club. (Powell was elected in 1952, Pressburger in 1970.) Here’s a short clip of them, in retirement, in conversation at the Savile, for a BBC Arena documentary in 1981.

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.