The English comic writer Stephen Potter is probably best-remembered for his tongue-in-cheek series of four Gamesmanship books (1947-58), offering not-always-ethical advice for gaining the upper hand in everyday situations.

Potter was also a keen club member, both in London (as a member of the Garrick and Savile Clubs) and elsewhere (the Leander Club in Henley; the Royal and Ancient Golf Club in St. Andrews; and the Edinburgh Croquet Club). Indeed, Potter took a strong interest in the gaming side of clubs, and was the first person to transcribe the rules of “Savile Snooker.” It is therefore unsurprising that clubs turned up in the Gamesmanship series.

Clubmanship

In the third book of the series, One-Upmanship (1952), we are introduced to the idea of “Clubmanship”, in which Potter applies his gamesmanship principles to the world of clubs.

Potter describes the “Clubs basic”, and explains its central assumption:

“Clubmanship proper consists, I always believe, in the continuous implication that you have Another life, so that even if you dig into your club regularly at 11.45 a.m. every day and stay there till, dazed with smoke, you feel your way out at midnight, you can still give the impression that it is a question of dropping in for a moment’s rest, quiet drink, or chat in between violent spasms of key jobs or valuable social activity.”

In short, club members need a hinterland. It is not enough to obsessively frequent your club every day - for therein lies the road to tedium. When in a club, you should draw on the wider world.

Potter does not, however, advocate neglecting your fellow members or staff. Far from it:

“Never make the mistake, either, of not remembering who your fellow clubmen are. On the contrary, know the names and, if possible, the salaries, of everybody, especially if they don’t know who you are. Take an interest in their professions. Be actually extremely nice to any crotchety club servant there happens to be and to unusually old members, particularly if they are expiring. It is by such little gracious acts, combined with inquiries about ‘that nephew of yours with chronic nosebleed’, that one-upness [sic] is established.”

The Two-Clubs approach

Potter believed:

“It is essential to belong to two clubs if you belong to one club. It doesn’t matter if your second club is a 5/- a year sub. affair in Greek Street; the double membership enables you, when at your main and proper club, to speak often in regretful discrimination about the advantages of your Other One.”

Yet Potter has a serious point here, extending well beyond the tongue-in-cheek petty snobbery which characterises so much of the Gamesmanship series. Potter also speaks of what members can bring by way of cultural hinterland, from one club to another; and argues that the two clubs should be “of sufficiently contrasted character”.

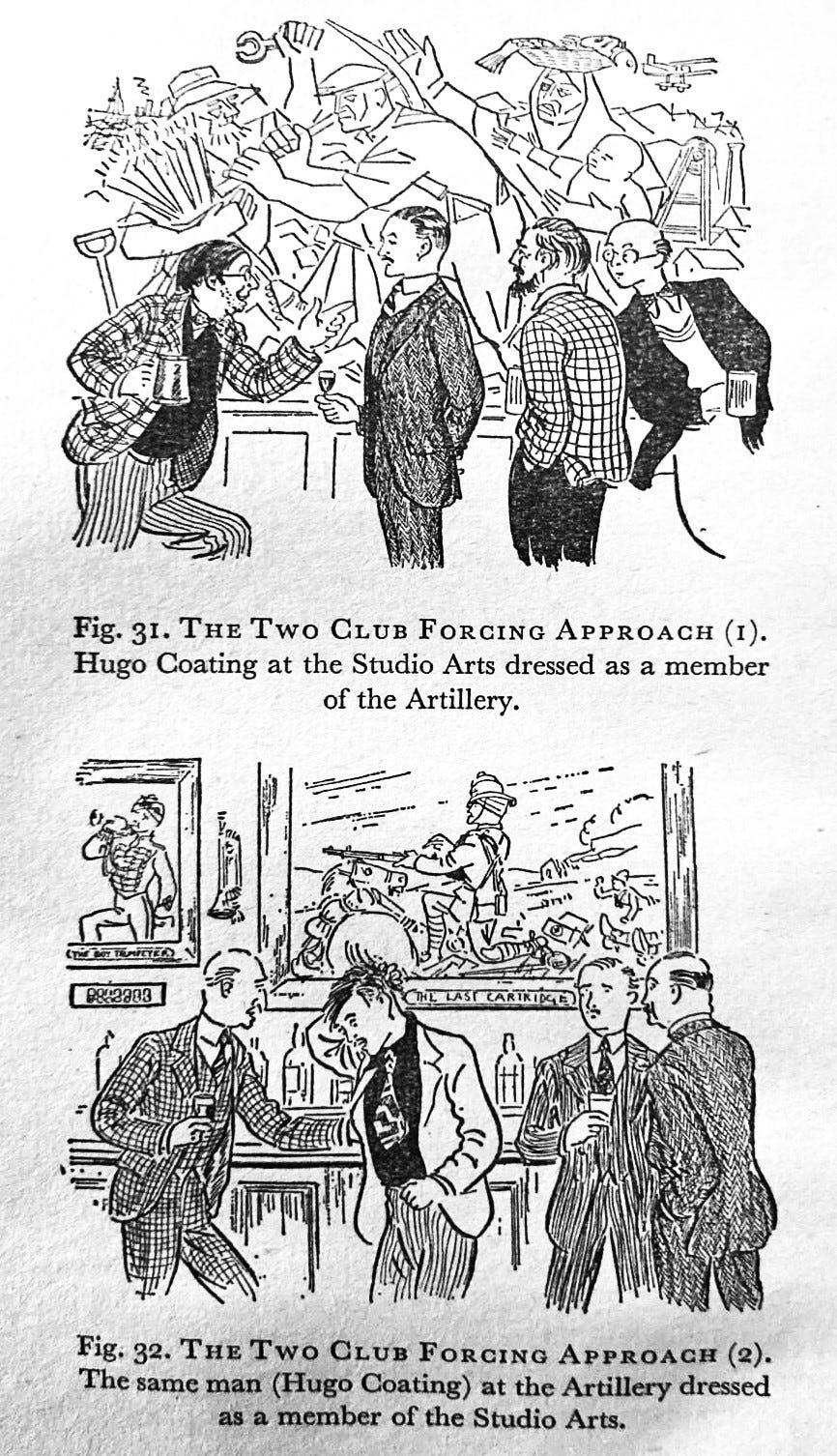

Frank Wilson’s illustration of the Two-Club Approach, enacted in the Artillery and Studio Arts Clubs (Stephen Potter, One-Upmanship (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1952), p. 126.)

He illustrates this with an example of two fictitious clubs, the Artillery and the Studio Arts. Broadly speaking, Potter advocates being every inch the seasoned military veteran when in the Studio Arts Club, and the struggling bohemian artist incarnate when in the Artillery Club. In both cases, the member will stand out, and will have something to say which is original for each setting.

Conclusion

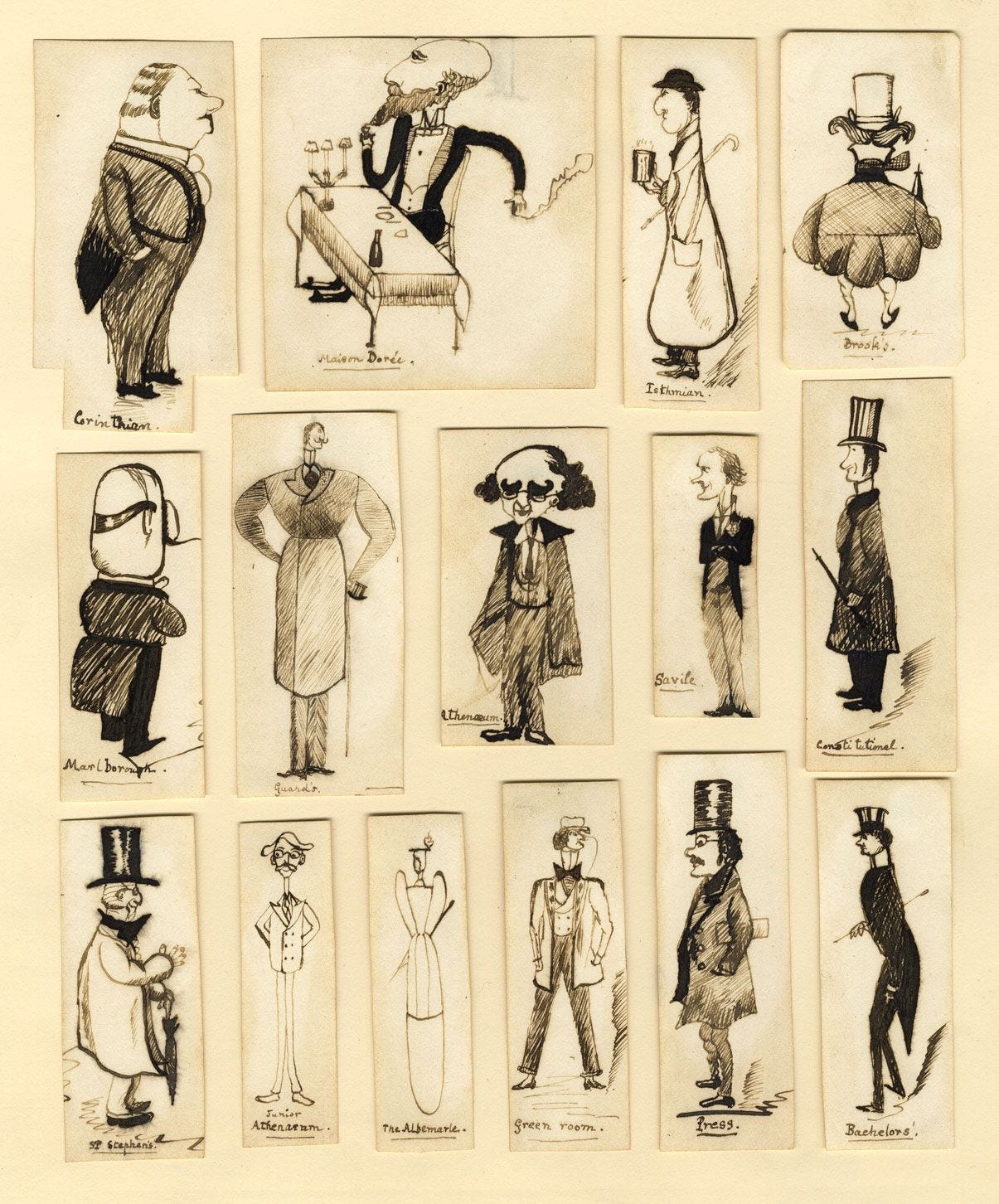

While Potter’s books are playful, and poke fun at the affectations of their subjects, he does have a point. Clubs would be awfully dull places if the members within each club conformed to one ‘type’ (see the late-Victorian cartoon of Clubland types by Max Beerbohm, below, which popularised this critique of each club having an archetypal member).

Therefore members will have more to offer their clubs, if they have something to offer from their outside lives and interests. And membership of multiple clubs of very different types certainly has its part to play. But I wouldn’t take Potter too seriously…

Original artwork of Victorian ‘Club Types’ by Max Beerbohm, drawn for Strand Magazine in 1892. The clubs depicted (l-r, top to bottom) are the Corinthian; Maison D'Orée; Isthmian; Brooks's; Marlborough; Guards; Athenæum; Savile; Constitutional; St. Stephen’s; Junior Athenæum; Albemarle; Green Room; Press; and Bachelors' Clubs. (Photo credit: Somerset & Wood, which auctioned off the original artwork.)

You can view the full and varied backlog of Clubland Substack articles, by clicking on the index below.

Index

Articles are centred around several distinct strands, so the below contains links to the main pieces, sorted by theme.